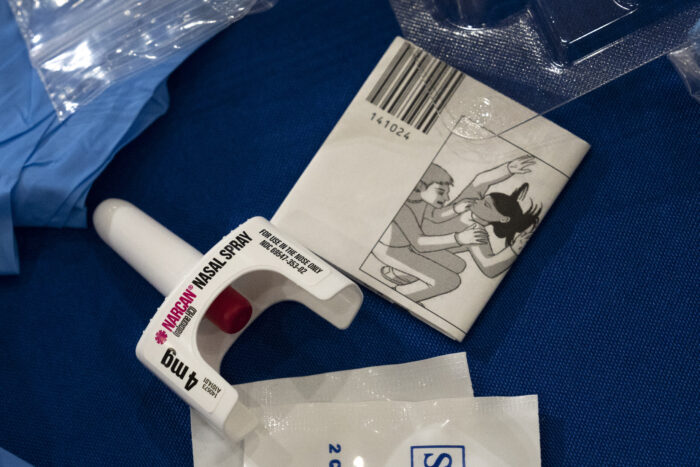

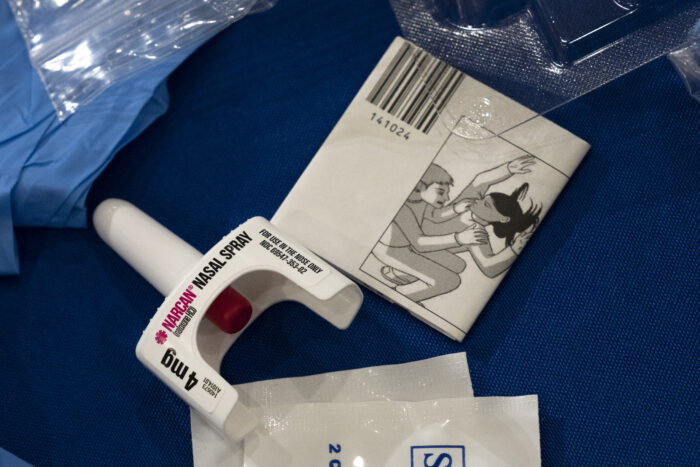

Naloxone (Narcan) nasal spray on display during a naloxone demonstration at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services headquarters in Washington, D.C., in 2023. Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images.

Written by David Miles

The author is a board-certified general pediatrician at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, a fellow of the American Academy of Pediatrics, and a member of the editorial board of the Academy of Pediatrics.

Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. openly talks about becoming addicted to heroin at age 15 after his father's assassination. Although some may link his introduction and misuse of opioids to his privileged access, substance use disorders in children are not limited to the wealthy and affluent. In fact, the only benefit of his privileged upbringing may have been the ability to afford the services he needed to treat his substance use disorder.

Nearly 60 years after teenager RFK Jr. first abused opioids, little has changed. In 2015, he found that overdose deaths among youth ages 15 to 19 had tripled. Most of it was unintentional.

Opioids now account for more than 75% of drug overdose deaths, and more children are dying from drug overdoses in Montgomery County. Across Maryland, the annual number of deaths among people under 25 due to opioid overdose increased slightly during the pandemic and has not declined since then. As difficult as it is for society to recognize these sobering statistics, it is even more difficult to reconcile them with the lack of treatment options for youth suffering from substance use disorder (also known as drug addiction). It's about being there.

As a child of the 1980s, I attended many Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) sessions that tried to help me resist the pressure to become interested in or try illegal drugs. Although well-intentioned, we recognize that focusing solely on prevention models may prevent us from devoting time and resources to people who may experiment with such drugs or become addicted to them. I've come to recognize it.

On a positive note, the Maryland General Assembly passed the “Start Talking Maryland Act” in 2017, requiring counties to make overdose treatment drugs (such as naloxone/Narcan) available in schools. Administration of naloxone is necessary and lifesaving in active overdose cases, but people who have overdosed (including children) often require treatment even after resuscitation. Long-term treatment remains difficult for most children, as most treatment centers only serve patients over the age of 18.

In my own practice as a pediatrician, I have often had patients and families approach me seeking drug rehabilitation treatment for themselves or their children. In one of the most unfortunate cases, the patient was on a waiting list and died shortly after turning 18 (qualifying for an adult drug rehabilitation program) before receiving treatment. This incident occurred in the wealthiest county (Montgomery) in one of the wealthiest states (Maryland) in the United States.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly exacerbated the opioid epidemic. One bright spot related to the pandemic was the implementation of federal regulations that make it easier to administer certain treatments (such as methadone) to treat substance use disorders, also known as drug-assisted treatment.

Data shows that the use of such agents reduces the need for inpatient detoxification services and improves patient survival, employment retention, and birth outcomes during pregnancy. These drugs can also reduce the risk of contracting HIV and hepatitis C, and have been associated with a reduction in opioid-related criminal activity.

Unfortunately, fewer than one-third of adolescents and adults eligible for such treatment actually receive it. Barriers include (in addition to young age) geographic, socio-economic, racial, and involvement with the criminal justice system.

Providing evidence-based, effective treatment to patients dealing with substance use disorders is personal. I have previously commented that as a result of my training as a physician here in Maryland, I may be complicit in a health care system that causes some patients to become addicted to opioids. Since then, as a professor, I have made it my mission to inform other aspiring veteran pediatricians about best practices for treating pediatric patients with substance use disorders.

Serving on the Maryland Opioid Recovery Fund Advisory Committee provides me with another opportunity to remind others (including Governor Wes Moore) to expand the scope of addiction treatment services for youth. He gave me. I hope that together we can advocate so that children suffering from opioid misuse no longer have to wait to get the care they need.

reissue

reissue

Source link