No one loves tech billionaires, for many good reasons. But every once in a while, someone comes up with an idea that could benefit many people in important ways. And when it happens, we should not only acknowledge it, but also strive to make it successful.

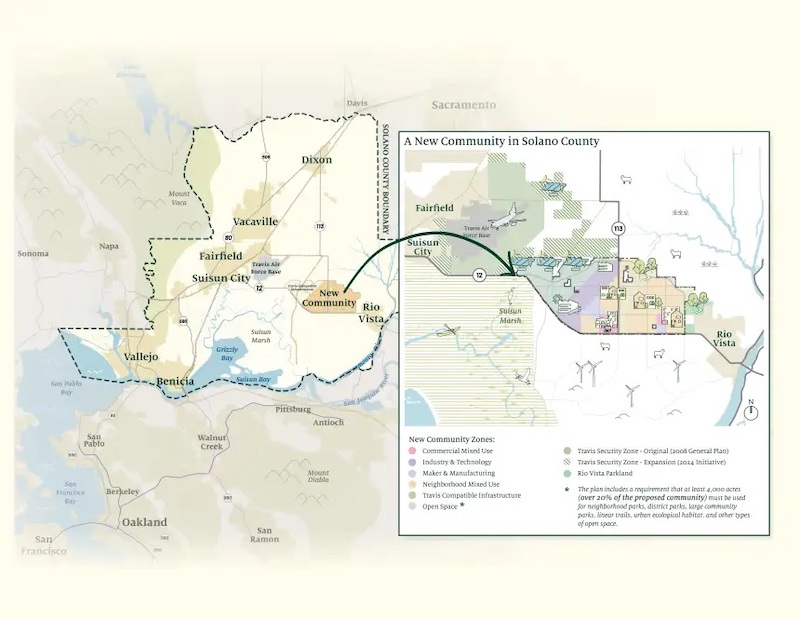

I'm talking about a proposal to build a new city in Solano County, California. The city has been given the unfortunate name “California Forever” by tone-deaf publicists. Since the plans surfaced in mid-2023, the reaction has been far more negative than positive, with concerns about land purchasing practices, the blighting of rural Solano County, the lack of public transportation, and the Travis Air Force. Writers voiced their anger over the impact. base. Several writers have grudgingly acknowledged that the new city might help meet California's housing needs, but praise is modest at best.

Map credit: California Forever

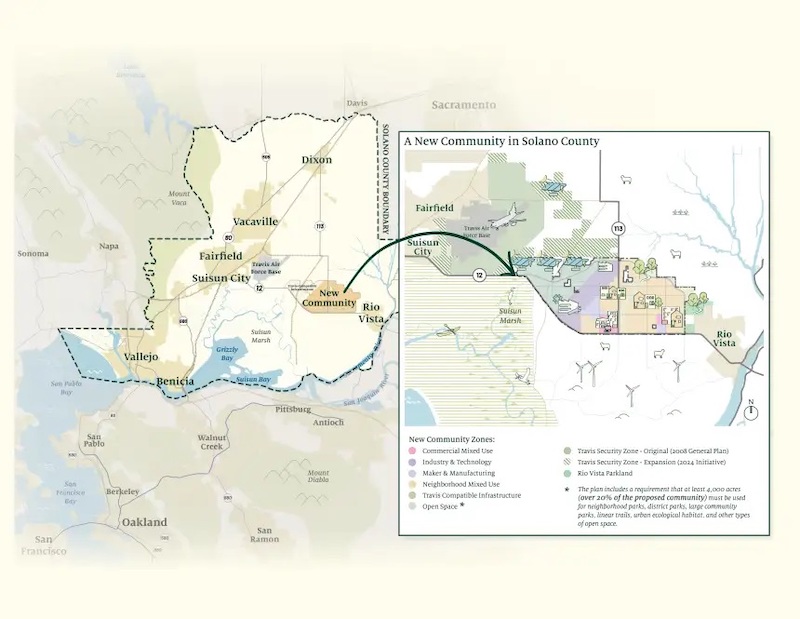

Map credit: California Forever

As a longtime urbanist and housing advocate, I would like to take a different approach. I think this has the potential to be one of the best developments in housing and urban growth to ever happen in the Bay Area. I say “maybe” because there are some serious “what ifs”. But the way to address these questions is not to hand California Forever a blank check or shoot it down. Instead, California, along with other states that care about the region's future, should engage with and embrace would-be city builders, but at a price. Because this is the first project anyone has proposed that could at least partially fill the Bay Area's massive housing shortage in our lifetimes.

But first, let's stop with the conspiracy theories. To be honest, if you want to build a new city or something, you need a lot of land. And he sees only two ways developers can get enough land. You can either own it from scratch, like at the Irvine Ranch in Orange County, or you can build it piece by piece. But if you're unlucky enough to already own 50,000 acres, the only way to get there is by stealth, so speculators don't come in and kill your project before it even starts. That's what James Rouse did 60 years ago when he gathered land in Columbia, Maryland. Today, Columbia is recognized as one of the best places to live in America and one of the most racially integrated. So let's get over it.

But the big problem is building enough housing. No one seriously disputes that. According to California, the Bay Area needs 441,000 more housing units by 2031. This is widely considered to be an underestimate of actual demand. YIMBY Action calls for 943,000, while an analysis by UCLA experts concluded a more plausible number would be closer to 700,000. Whatever the exact number is, it's a big number.

Achieving a modest population in the state would require a significant increase in housing production in the Bay Area. Based on construction permits over the past five years, Alameda County would need to double its annual production, Marin would need to increase from 225 to 1,800 cylinders a year, and San Francisco would need to increase from 3,000 to more than 10,000 cylinders a year. If someone believes that numbers like that can be achieved through zoning reform and transit-oriented development, a few houses here and some multifamily development, they probably also believe in the Tooth Fairy.

Certainly, there is some room for growth without building new cities. Upzoning will encourage higher-density redevelopment and unlock the potential of underutilized parcels everywhere. Experience shows that ADUs create a significant number of new homes in people's backyards. But those who chant the mantra “zoning, idiot” have no idea how difficult the development process is, or, as they say, how difficult it is to get development off the ground in the Bay Area.

That's where California Forever comes into play. If they can provide 160,000 or so homes, which is comfortably within the amount of land they manage, it will be a huge blow to meeting the Bay Area's housing needs and closing the housing gap. Dew. is necessary, and what the region can achieve in other ways. It would go much further towards meeting these needs than anything else currently being considered.

Despite the obvious flaws in this proposal, it is ultimately a litmus test. Are California public officials and housing advocates serious about addressing Bay Area housing needs, even at the risk of antagonizing large numbers of people, or are they just housing for them? Another set of performative gestures?

That doesn't mean California Forever doesn't have some serious flaws, two in particular. First, it has not committed to including affordable housing. The plan talks about affordable density and workforce housing, but makes no promise to provide housing at price levels that the area's low- and moderate-income households can afford. However, there are hundreds of low-income housing units elsewhere in the county, although developers have offered to finance what is likely to be the case at most. Second, the plan does not provide efficient transportation connections to other parts of the Bay Area.

Both need to be addressed, and the only way that can happen is if the state makes accepting projects a condition of solving both problems and works with developers to make both happen. Without significant state involvement, it is impossible for California Forever to provide viable transportation connections to the rest of the region, and we all know that.

Ultimately one of three things will happen. The state will be able to embrace this project and ensure it is delivered in a manner that best meets California's housing needs and sustainability goals. Or maybe somehow the developers will prevail despite the opposition and California Forever will be built, but it will fall far short of what was hoped for. Otherwise, the nation will cease to exist, and it will destroy its best opportunity to build the housing it so desperately needs.