As a child, John de la Parra's idea of play was exploring the plants and crops on his family's small farm in Boaz, Alabama. His greatest influence was his grandmother, who introduced him to the medicinal and therapeutic properties of plants. Over time, this passion blossomed into a love of science, and he began to combine ancient wisdom with modern scientific discoveries.

Today, de la Parra is living out his childhood dream as an ethnobotanist and plant chemist, and director of the Rockefeller Foundation's Food Initiative, where he is part of an innovative team changing the way we understand food.

The truth is, we know very little about what we are eating.

“For centuries, traditional societies have revered the medicinal and therapeutic properties of certain foods,” he says, “but the scientific community has only just scratched the surface about the biochemical composition and properties of the foods we consume.”

The idea that food is medicine has been central to human culture for thousands of years, with roots in a rich history and complex belief systems. Traditional societies have meticulously passed down knowledge about the medicinal properties of certain foods from generation to generation. As we move into the era of evidence-based practice, we find ourselves at an interesting crossroads. It is about investigating ancient traditions to uncover scientific truths while at the same time respecting the cultural context that gave rise to them.

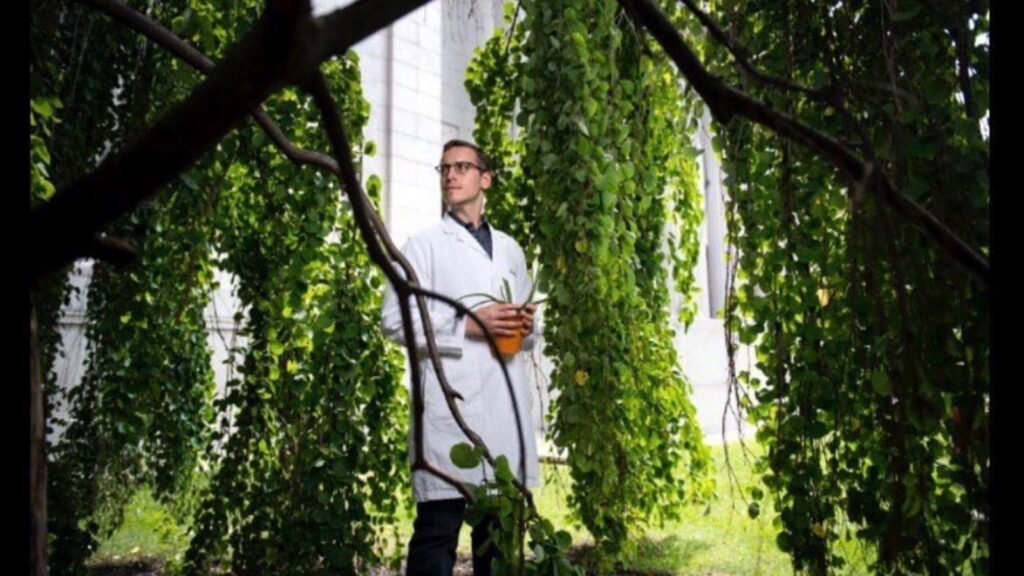

john de la para

john de la para

To be honest, when you look at the numbers, it seems like science is lagging behind.

Consider this. Our food contains many small parts called biomolecules, such as proteins, carbohydrates, and vitamins, that help our bodies work. However, we only catalog a fraction of them on a daily basis, about 150 out of tens of thousands, or less than 1% to be exact.

“A significant portion of what humans consume remains a scientific mystery,” asserts Selena Ahmed, global director of the American Heart Association's Periodic Table of Foods Initiative (PTFI). “Not only are these foods invisible to nutrition, but an estimated 95% of biomolecules in foods escape our analysis and are not shown on food labels. We may think we know what we eat, but most biomolecules do.'' Our understanding is limited because we only have time. ”

But that's about to change.

The groundbreaking PTFI, developed by the Rockefeller Foundation, includes a research database that captures known and previously unknown biochemical properties or “dark matter” in foods. PTFI's biochemical data is collected using cutting-edge technologies such as high-resolution mass spectrometry and artificial intelligence, providing a lens through which to finally scientifically validate the secrets of ancient dietary wisdom.

PTFI's standardized analytical methods and tools identify thousands of ingredients in food and laboratories. [+] In the world.

getty

“For decades, food has been viewed through a reductionist lens, often simplified down to calories and essential nutrients. PTFI is committed to fundamentally changing this approach for the better,” said Maya Rajasekaran, Managing Director Africa at Biodiversity Alliance and CIAT, and Director of Strategic Integration and Engagement at PTFI.

With support from the American Heart Association and assistance from Bioversity International and CIAT, PTFI has created an initial list of 1,650 foods from around the world, many of which have been cultivated by indigenous peoples for thousands of years. It has been valued for its medicinal properties in many cultures. The scientific community has already started collecting data on about 500 of them.

PTFI data is publicly available through MarkerLab, an online data visualization tool. Chi-Ming Chien, developer and co-founder of Verso Biosciences, said the interface helps users visualize and explore data in a clear and informative way, allowing researchers to “ Compare foods and compounds to discover the next scientific discoveries in food, nutrition, agriculture, and health.”

But like ancient wisdom, data has to tell a story.

“Humans have a desire to understand the natural world around them,” Dellapara says. “We collect all the empirical chemical data about foods, but we also collect metadata, additional information that describes those foods, such as how they were grown. Where? Was it cultivated? Why does it make sense? How is this food used in certain cultures? These ideas about traditional ecological knowledge and traditional knowledge are particularly appealing. The Periodic Table of Foods Initiative is, in many ways, the world's most comprehensive edible biodiversity resource.”

John de la Parra at work

john de la para

Understanding the composition of food, including its diverse biomolecules and their abundance across a variety of conditions, is key to empowering stakeholders across the food system. This knowledge enables informed decision-making that improves the health of both the planet and humanity, while also helping to bridge the gap between traditional wisdom and modern science.

This work is timely as the world grapples with diet-related diseases and climate change. A narrow focus on a few staple crops such as wheat, corn and rice has led to a loss of dietary diversity and resilience. PTFI's diverse food list includes fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, animals and even fungi and lichens, which are essential to building a more sustainable and resilient food system.

“As the number of foods in our database grows, so will our collective understanding of the role of food in human and planetary health,” says Tracy Shafizadeh, developer and director at Verso Biosciences. .

Notably, more than 1,000 foods included in the PTFI repository are not included in any globally recognized food composition databases, highlighting significant gaps in nutritional knowledge.

One example the PTFI team looked at is wattleseed, a member of the Acacia genus, a traditional food of Australian Aboriginal people. Despite a long history of use, many of the 120 species in the genus are absent from global food databases. PTFI is shining a spotlight on these overlooked foods, asking important questions about their nutritional and medicinal properties, and their role in ecosystems.

Wattleseed, traditional Australian Aboriginal food

Fairfax Media (via Getty Images)

PTFI's efforts also resonate with broader environmental goals. Bruce Jarman, chair of PTFI's Scientific Advisory Board and director of the Foods for Health Institute at the University of California, Davis, said, “Agriculture is a major contributor to climate change and the destruction of our planet. The only way, the only necessary step, is to know what food is.”

To ensure cultural, geographical and climatic inclusivity, PTFI has established nine Centers of Excellence in each major continent, seven of which are located in low- and middle-income countries, with a focus on food biomolecular analysis. and its regional translation. These centers include the University of Adelaide in Australia, the University of California, Davis, the Ethiopian Institute of Public Health, the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Ghana, the Pontificia University Javeriana in Colombia, and the Salvador Zubiran National Institute of Nutritional Medicine in India. is included. Mexico, Mahidol University in Thailand, University of the South Pacific, and Wageningen University and Research Institute in the Netherlands.

“In addition to supporting the collection of food samples from around the world, local agencies will lead this effort so that local people can ask culturally appropriate questions about their food. '' explains de la Parra. “When it comes to culturally sensitive foods, we pay close attention to how we collect and share data…We make sure that all information is shared with communities analyzing foods that are spiritually or culturally important to them. Make sure it doesn't have to be publicly accessible.

The nine centers of excellence also allow for comparison across different contexts.

“With PTFI, our methodology becomes standardized,” de la Parra says. “So if I analyze an apple in the United States and someone in another country analyzes another apple, we can literally compare apples to apples.”

This work has a deep meaning. PTFI can validate traditional practices and pave the way for new evidence-based dietary guidelines. This could lead to more natural, accessible, and effective health solutions, and dovetail perfectly with the growing interest in holistic health.

“There's also an opportunity for advances in personalized nutrition,” de la Parra added. “We each have a genetic heritage that evolved eating specific foods in specific places. Knowing the chemistry of those foods may allow us to make more precise health recommendations.”

Understanding the complex biochemistry of food can help build sustainable food systems using holistic approaches that promote diversity, sustainability, and resilience in food production and consumption. Masu.

The Periodic Table of Foods Initiative is more than just a scientific endeavor. It is a bridge between past and future, a fusion of ancient wisdom and cutting-edge technology. By continuing to explore and test the medicinal properties of traditional foods, we open new possibilities for health, sustainability and global well-being. This is the beginning of a new era of understanding food as medicine, a time of honoring the past while embracing the future.

Marcelino Aprina, chief of Ardeia Novo Paraiso in Brazil's western Amazon region,… [+] La Brea has babak fruit and ranitidine hydrochloride tablets, both of which are used in traditional and modern medicine to treat stomach problems, respectively. (Photo by CARL DE SOUZA/AFP via Getty Images)

AFP (via Getty Images)

Source link