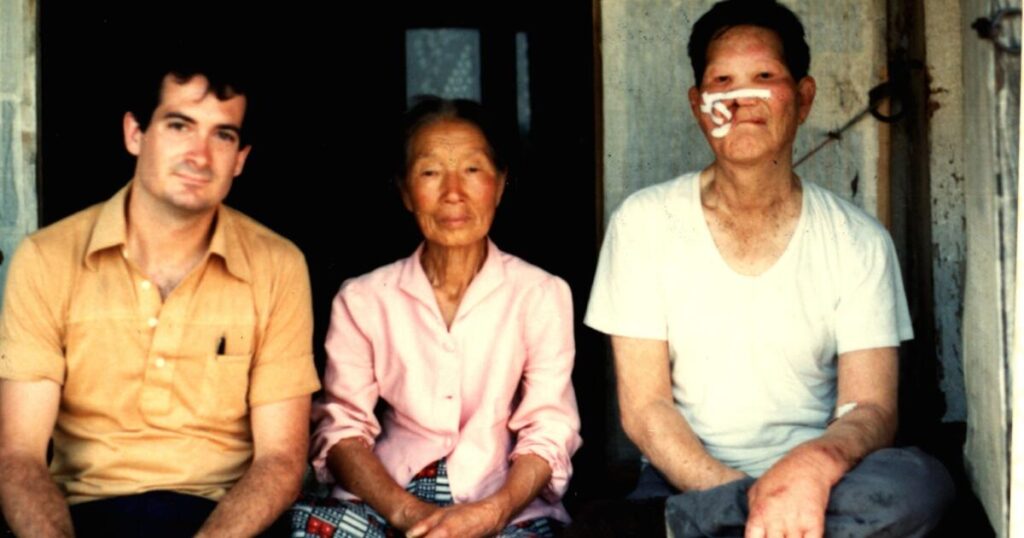

Courtright is an ophthalmology epidemiologist and lives in Rancho Bernardo.

For most Americans, May 18, 1980, marks the day of the largest volcanic eruption in the United States' lifetime: Mount St. Helens in Washington erupted. For me, living in a village on the other side of the Pacific, that was the day South Korean troops massacred students in the nearby city of Gwangju. I was in Korea at the time as a U.S. Peace Corps volunteer, doing leprosy relief work. The massacre sparked a popular uprising that left hundreds killed, drove the military from the city, and led to a week-long siege of Gwangju that was brutally put down.

The next morning, as I got off the bus in Gwangju with the two patients I was accompanying for surgery, I witnessed the shocking violence people had suffered. I will never forget watching soldiers beat to death a young man and hearing my grandmother scream, “They killed him.” Those 10 days changed Korea forever. And they changed me forever.

In 2020, I published my memoir, Witnessing Gwangju, but in the four years since then, I've realized that I still have a lot to learn. While I'm still learning, here are three things I've learned.

First, beware of single narratives. Recently in Seoul, I happened upon hundreds of protesters. Posters plastered everywhere made their message clear: they claimed that the Gwangju incident never happened, that it was simply the fault of rebellious southerners, or a conspiracy instigated by North Korea! Memories of the riots raced through my veins, and I wanted to scream, “You've got to be kidding me! Your sons and daughters were killed there!”

Second, to write down all the stories. For many years after the Gwangju uprising, collecting and compiling the events of May 1980 was considered an act of treason. When the military regime fell, stories from Gwangju started to be written down. Returning to South Korea, I wondered: what stories were not written down? I soon found the answer.

At a taxi stand in Nampyeong, a small town on the outskirts of Gwangju, I asked if anyone knew my village. The person who did was Mr. Shin, who was the same age as me and the oldest taxi driver there. I asked him about the Gwangju Uprising. I learned that his younger brother had been shot and killed by soldiers on his way from Gwangju to Nampyeong.

The images of bullet-riddled buses and taxis that were burned into my mind when I walked that road in 1980 now had a character who humanized the inhuman act. The night before I walked that road in 1980, a murder had taken place, and although the blood had not been washed away, the body was gone. Shin's family had never seen the body, and he had never spoken about his experience until now. I wonder how many stories are still lost. Any event as momentous as the Gwangju Uprising deserves all the stories to be told. This is not to relive the trauma, but to understand it and learn from it. We need the stories of the soldiers who perpetrated it as much as we need the stories of the victims.

Where else are we missing stories? Without stories, we diminish. To understand life- and nation-changing events, it's important to have the full tapestry of stories at our fingertips.

Finally, celebrate successes. During my last trip to Korea, a reporter from a local paper heard I was in Gwangju and asked to interview me. We commiserated about the difficulty of having thoughtful discussions with Koreans about the issue. He told me that young people in Gwangju don't want to talk about the democratization movement because they're embarrassed. How can that be? They should celebrate all that the democratization movement accomplished. It set Korea on the path to democracy. All Koreans owe a debt of gratitude to the citizens of Gwangju. Even with the military up their necks from the edge of town, the people of Gwangju kept their city intact, functioning, and vibrant. Their resilience was remarkable.

Too much attention has been paid to the horrors of the Gwangju Uprising, and not enough attention to what people should be proud of. No one should be celebrating the uprising, but we should celebrate what it accomplished.

Any political or popular event like the Gwangju Uprising is complex, and it is important to find what we can celebrate.

Learning from trauma is a personal activity, but we can all learn from events like Gwangju, if only to prevent them from happening again.