The rising cost of food is affecting people across Canada. It's affecting nearly everyone, but it's more than just an inconvenience. It's a major threat to food security for many Canadians. Understanding why food costs are so high, and why they are fluctuating, is critical to the well-being of our society.

Unfortunately, there is a lack of consensus on why food prices are so high. Explanations in reports such as the Canadian Food Price Report and in the news media range from the war in Ukraine to supply chain issues to carbon taxes.

Every year the key drivers seem to change, but if the growing consumer boycott of Loblaw is any indication, consumers are demanding better answers.

So we completed a rigorous analysis of the most prominent reports shaping the food price narrative in Canada, including 12 years of Canadian Food Price Reports and 39 reports from Statistics Canada. Our findings, which are peer-reviewed and soon to be published in Canadian Food Studies, are both insightful and concerning.

Lacking scientific rigor

Our analysis finds that most of the claims about food prices in these reports lack scientific rigor: almost two-thirds of explanations for price changes are not supported by evidence, and discussions of the causes of food inflation are often incomplete and miss the link between cause and effect.

For example, the report may identify the impacts of bad weather, climate change and changes in retail demand, but it doesn't detail how that will translate into actual price increases at the register.

Understanding why food prices are so high and why they're changing is important to the well-being of our society. The Canadian Press/Christine Mussi

British philosopher Stephen E. Toulmin presented a simple approach to assessing the quality of a scientific argument in 1958. Simply put, a complete scientific argument needs three elements: a claim, testable observations or data on which to support that claim, and a clear theory or assumptions that logically connect the claim and the data.

Rigorous scientific arguments need to support the strength of their hypotheses and qualify their claims with reasonable counterarguments, but most of the arguments in these reports fall short of this, providing no even basic evidence to support their claims.

These reports are not scientific publications but rather fall into the category of “grey literature” – information produced outside traditional academic publishing channels.

“Nevertheless, these reports are published under the logos of academic and government institutions. Given the prominence of these reports in Canadian media and policy, we believe it is important for the public to know that the arguments presented in these reports do not meet scientific standards.”

Overlooking important issues

While the report does identify underlying drivers of food prices, it also has some notable omissions.

While extreme weather and climate change are sometimes cited as abstract reasons for rising food prices, major environmental issues such as biodiversity loss and declining fish stocks are not mentioned in the report, even though they are widely recognised to affect food prices and availability.

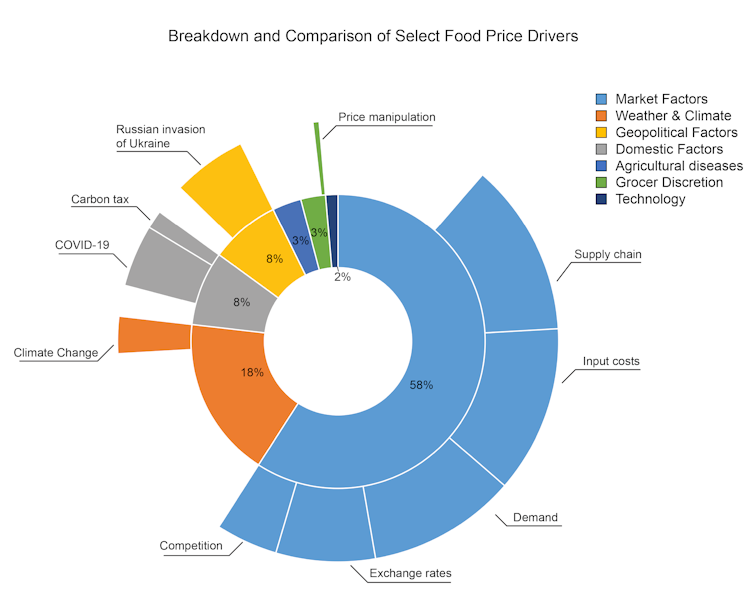

Breakdown of factors identified in food price reports from the past 12 years. (Pentz et al., forthcoming), provided by authors (not for reuse).

These reports also give little consideration to the decisions made by grocers and other private companies about food prices. Increasing consolidation and concentration in the food sector are structural issues that deserve scrutiny.

The bread price-fixing scandal of a few years ago showed how a lack of competition can enable price manipulation to the detriment of consumers, and the Canadian Competition Bureau recently announced it was opening an investigation into the owners of Loblaws and Sobeys for alleged anti-competitive conduct.

In the United States, there is also strong evidence that the private sector is exploiting supply chain problems and inflation to make unfair profits. Similarly, the Federal Trade Commission recently found that major grocers used the pandemic as a smokescreen to inflate profits at the public's expense.

Read more: Food giants reap huge profits in times of crisis

Grocery store profits are also growing in Canada, so it's fair to ask tough questions about the extent to which their decisions are impacting cashier pain.

Our analysis found that of more than 200 explanations for food price fluctuations, only 3% pointed to the actions of grocers or other private sector institutions as responsible for price increases, reflecting a tendency to portray food prices as volatile and highly uncertain.

Other issues, such as over-reliance on fossil fuels throughout the supply chain, are not mentioned.

A new approach is needed

Without rigorous, transparent analysis, we will have an incomplete understanding of why food is so expensive and what can be done about it.

What we need is a new approach. Food is a human right, but it is also a special right because we depend on the private sector to provide it. We should expect higher standards than other consumer goods, but the private sector can hardly be denied the benefit of the doubt, given its history of price fixing.

A positive step towards producing reliable evidence on food prices would be to incorporate transparency measures into the code of conduct the Canadian government is developing in collaboration with grocers, which could include third-party audits, open data sharing, and a clear breakdown of the drivers of price fluctuations from farm to store.

Read more: New grocery code of conduct should benefit both Canadians and the food industry

Peer review of research is a key aspect of responsible science, and in our paper we look at the process provided by the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat for federal fisheries science as a model for government-based food price reporting.

When it comes to essential goods like food, Canadians deserve a full accounting. For decades, policies and markets have been designed to keep food cheap, but at the expense of workers and the environment.

If rising food prices are beginning to reflect the true social and environmental costs of production, then we need a broader conversation about reforming our economies and lives to ensure that everyone can afford food. But without a clear understanding of the real drivers, we lack the information we need to design policies that protect the rights and well-being of Canadians.

Dr. Brian Pentz, currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Nature Conservancy, is the lead author of the study and contributed to the writing of this article.