Lloyd Axworthy is a former Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs and currently serves as Chair of the World Council on Refugees and Migrants. He has led numerous Canadian election observation missions, including to Ukraine in 2019. Alain Locke is a former Canadian Minister of Justice, Attorney General and Canadian Ambassador to the United Nations, and currently serves as a member of the Transatlantic Commission on Election Integrity.

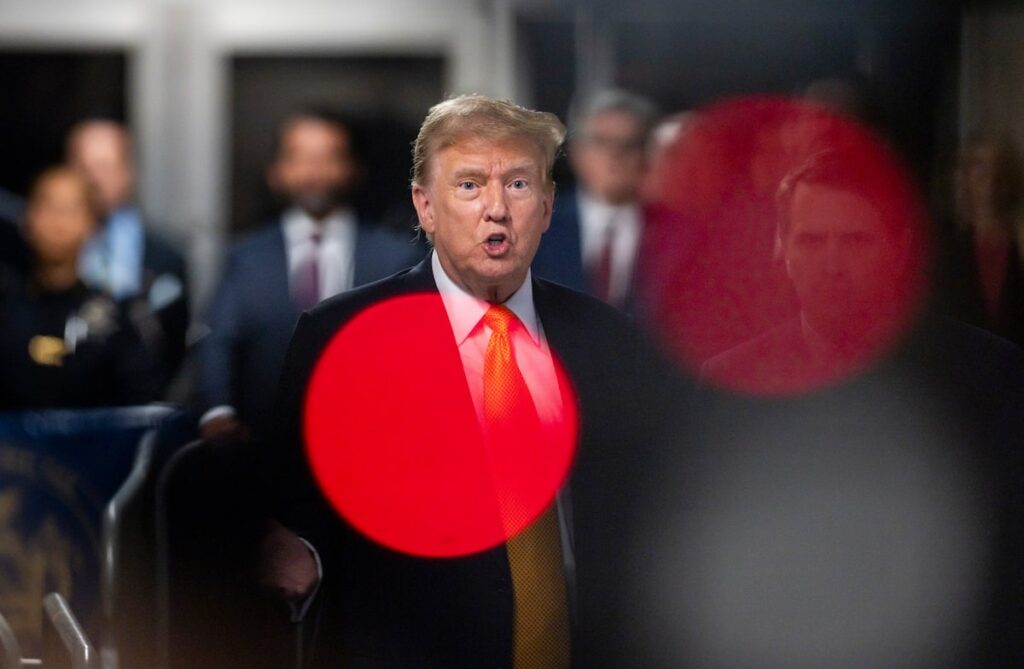

In a year when half of the world's adults will vote in national elections, one election stands out as one that will determine not just the country but its very existence: the US presidential election in November. Returning former President Donald Trump to the White House would of course mean a return to his erratic and disruptive style of governance, but it would also install a leaning authoritarian regime that would endanger democratic governance around the world. Moreover, the Republican candidate and his allies have already signaled that they will only accept the results of the next election if he wins, and they have pushed the claim that the 2020 election was stolen, which sparked the January 6th riots at the US Capitol.

So we face a double hazard: chaos if Trump wins, and chaos if he loses.

The Canadian government has reportedly adopted a “Team Canada” stance in response to a possible Trump presidency, a welcome and measured response, but isn't it equally important to help U.S. allies ensure that their elections are free and fair, without preemptively sowing doubt?

The international community can contribute to this by using the established practice of independent and impartial election observation. Coalitions of interested democracies could deploy observers to observe, assess, and report on how elections are conducted. Certification by such a credible coalition would go a long way to blunt partisan attacks by sour-poor electors and would send a signal that false claims of “fraud” would be disputed.

International monitoring of US elections is not unprecedented. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) has been invited to monitor US presidential elections going back to 2002. However, Russia is an OSCE member state, and the Kremlin may try to influence the reports. Indeed, the 2019 Ukrainian elections called into question the credibility of the OSCE mission. Meanwhile, monitoring by domestic institutions such as the National Democratic and Republican Institute will also be a challenge. In the current political climate, anything they report will surely be dismissed as biased. Even entrusting the US justice system with judging the fairness of the elections will be problematic, as it has become increasingly partisan.

Canada has the experience and connections to lead both in creating an international coalition of democracies and in conducting the monitoring itself. Over the past 18 years, Canada’s national election monitoring organization, Canadem, has sent delegations to more than a dozen countries. In recent years, Canada has produced thorough and credible reports on elections in countries such as Ukraine, Peru and Sierra Leone.

Canada's U.S. consulate network, with 23 representatives across the country, is also ideally positioned to monitor election integrity in the U.S. These offices can work with international partners to monitor and report on election integrity.

Of course, Canada is in the midst of an investigation into allegations of foreign interference in its elections, which has led the government to introduce legislation to address that threat. It has also pioneered technology to counter cyberattacks by malicious foreign powers. We can use some of the lessons we've learned from monitoring U.S. elections to strengthen our neighbors' democracies and prepare for international monitoring of our own federal elections in the next year or so.

But there is another challenge: convincing the United States to accept our help. Americans tend to see their own system as a model of democracy, and may be uncomfortable with the very idea of international monitoring of elections. But we can temper that reaction by reminding them that Democracy Summits, twice convened by President Joe Biden himself, have advocated for coordinating international efforts to safeguard the integrity of elections in all democracies. The United States, as the most visible of them all, can only lead by example. And since a hallmark of resilient democracies is their willingness to accept external monitoring, welcoming independent monitoring should be seen as a sign of strength, not weakness.

Having run for office 15 times between us, we know firsthand the power of the will of the people expressed through the ballot box. And while the whole world is watching how the U.S. presidential election is conducted and how it turns out, no country has a greater interest in a free and fair election, and in the health of U.S. democracy, than Canada. And so we should lead an international effort to observe and evaluate its fairness.