When Donald Trump is relaxing — or as relaxed as he can be while on trial for 34 felony counts of falsifying business records — his socks are visible. They are a thin black material, probably cashmere, and are only visible when he leans back in his chair, exposing his calves through their elasticated seams.

I know this thanks to Isabel Brauman, a brilliant artist sketching the theatrics of Trump's hush-money trial from the second row of the courtroom, dressed in a show-stopping outfit for the day's testimony. Brauman lives for these little moments, the kind that reduce even a swaggering former president to a mere mortal: a man whose skin flushes red when he's nervous, whose forehead turns orange-brown, whose mouth purses and shadows his chin when he's angry.

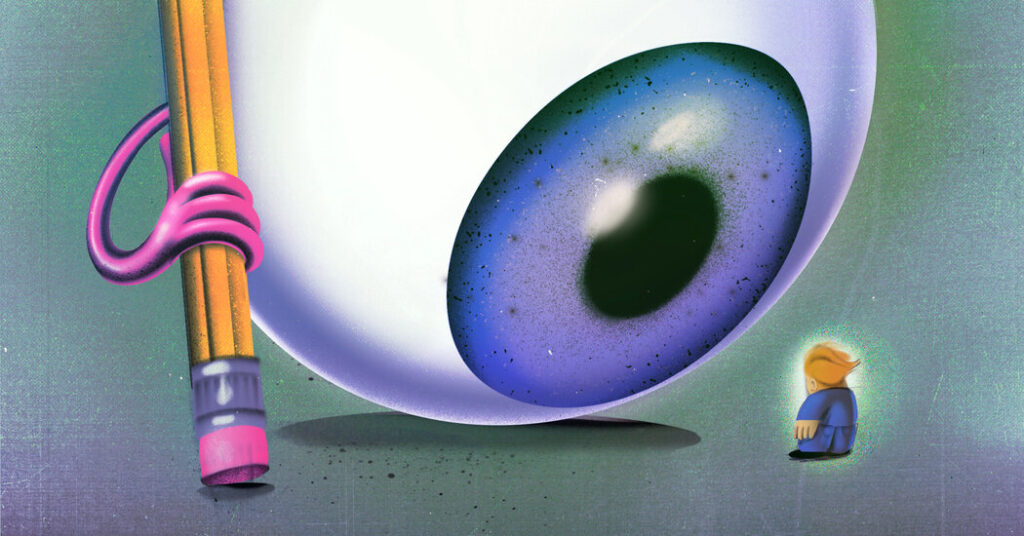

She absorbed it all, and it all is now reflected in her work, now published in New York magazine. But rather than capturing a key moment or providing a realistic portrayal of the day's events, Ms. Brohman's expressive images traverse space and time. She uses watercolors, colored pencils, pencils and glitter pens, sometimes pinching them with tweezers for texture or scrawling words in the corners. In her portraits of Mr. Trump, he is at once frantic and stocky; in shades of blue and purple, Stormy Daniels looks emotionally wounded.

“The other artists are very professional,” she told me recently. “I would happily say I'm not professional.”

I got to know Brauman because, while most of the rest of the country was obsessed with the Trump trial itself, I had spent the past few months fascinated by the world of courtroom artists painting the Trump trial, a world that Brauman both belongs to and doesn't belong to.

For the past year, Brauman, 30, has been sitting in the courtroom's front row, engaging in an awkward symbiosis with three veteran artists who have churned out photos for Reuters, CNN and the Associated Press, reprinted around the world, just as they have for more than four decades. These artists are legendary in the world of New York courtrooms. Three women, all well over 50, among the last practitioners of a disappearing profession, and their perspectives have suddenly become incredibly important. In a rare space where cameras are banned, they are the ones watching the nation watch the most important political trial in American history.

“Sketch ladies,” as Broerman calls these women, exist because of a legal vestige that all but bans cameras in New York state and federal courts. The judge in the case made a slight exception, allowing a small group of photographers to briefly film Trump at the start of each day, during which he strikes poses and his usual grimaces, leaving the more raw, unscripted moments entirely up to the artists.

I first sat behind the women sketching during the E. Jean Carroll sexual assault and libel trial, and was fascinated by their work. With their black-rimmed glasses and draped scarves and chalk marks on their fingers, the women seemed at odds with the stuffy atmosphere of the room. In tense moments, the only sound was the scratching of paper.

I watched Christine Cornell, 69, use pale yellow pastel to capture the outline of Trump's hair, tracing its curves like a lemon meringue, and Jane Rosenberg, 73, peer through tiny binoculars into the side of his face, carving a deep shadow into his cheek. Elizabeth Williams, who would only identify herself as the youngest of the three, scribbled in ink pen an image that was somewhat reminiscent of Munch's “The Scream,” as Carol tearfully testified.

There was something intriguing about the fact that the public was only seeing the Carroll trial (a trial about sexual violence, misogyny, and power) through the eyes of older women. I wondered if they were identifying with Carroll in a way that imbued her sketch with a touch of resolve. Am I the only one who found the Trump sketch a bit cynical?

Then came the hush money trial. Rosenberg's striking sketch, taken during Trump's arraignment, appeared on the cover of The New Yorker – the magazine's first courtroom drawing. Some likened Rosenberg's drawing of Trump to a gargoyle, others to the Grinch. Was the exaggerated, pastel-colored lips meant to convey some kind of message?

All the women are adamant: “No. Their job is to paint what they see. No commentary, no hidden messages, just facts with ink and chalk.”

In fact, they say, drawing Trump isn't much different than any other day. They've painted murderers, rapists, mobsters and even Trump himself, who stood in court in a sports antitrust case in the 1980s (he was the owner of a New Jersey football team). Rosenberg was nearby when Osama bin Laden's personal assistant lunged at the judge and was dragged away by security while on trial on terrorism charges. Cornell was asked out on a date while drawing another terrorist convicted of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing (she declined). The women were summoned to have their hairlines trimmed, wrinkles smoothed out or “made to look sexy,” as Donald Trump Jr. requested during his father's civil fraud trial.

“It's a strange life,” Cornell said when I visited him at his New Jersey home.

The next time I met Cornell, she was in the ladies' room on the 15th floor of the New York State Supreme Court building in lower Manhattan, where she had propped Daniels's drawing up against a radiator and commented that it was “too cute,” a place where, I learned, she and other artists would retreat to during breaks to photograph their sketches — hers on a radiator, Rosenberg on a trash can.

The women work at a ferocious pace, sometimes producing six or seven sketches a day, often with only a few minutes to complete each, and under immense pressure not to miss a single crucial moment — none of this lends itself to particularly deep reflection, and that's not the nature of the work after all.

But it inevitably requires a certain amount of interpretation: drawing facial expressions, occasionally reading lip movements, and deciding which moments to focus on and which not, like Trump yawning at the start of his courtroom appearance. “I hesitated a little bit,” Rosenberg told me. “I thought it might be a little mean and disrespectful, but I did it.”

These are all small subjective acts, small decisions that contribute to our understanding of the dynamics of mundane, sometimes sensational, places.

And even the most even-handed artists make choices, such as accentuating Trump's “accordion hands,” as Ms. Williams does, or the “caterpillar” eyebrows that Ms. Cornell favors. While Mr. Rosenberg's Trump tends to be angular and frowning, Mr. Williams's is more cartoonish and bewildered.

But if the women in the sketches try to downplay the importance of these choices, Brauman emphasizes that, without pretending to be objective, her interest in the courtroom comes from a personal reason: her own lawsuit against a former star university professor she has accused of sexual assault.

From that experience, she went on to paint the Johnny Depp vs. Amber Heard libel trial, posing for a professional courtroom artist she met there to secure a seat. Then she painted the actor Danny Masterson rape conviction, E. Jean Carroll libel trial, and finally Trump. To her, this is high art, the kind you want to put in a gallery or museum, but it's also cathartic, healing. In her case, she says, the professor had a lot in common with Trump.

Brauman's foray into courtroom sketching may be fleeting, but she quickly discovered that there are simultaneous dynamics in any trial: There's the main performance, performed for the jury. And then there's the sideshow, sometimes literally, that artists zoom in on. (Brauman told me that at the same time that former Trump aide Hope Hicks broke down in tears on the witness stand, she was using binoculars to study the face of one of Trump's lawyers; she saw the lawyer mouth “thank goodness” to his client.)

Finally, there's interpretation. Broerman describes watching Daniels leave the courtroom after her testimony, lifting her chin just a little before she was about to leave through a side door, in plain view of Trump. “I was like, 'Oh, I see what that is. That's pride,'” she said, standing up and mimicking the movement at the coffee shop where we met. She was attaching meaning rather than testifying. That's important to her work, and a kind of contrast to other artists.

Ms. Brauman's theater-like sense and the attention her approach has given her haven't always been well received by her colleagues, who were initially suspicious of her and excluded her from negotiations for a front-row seat. But like the courtroom itself, which Mr. Trump initially complained was “frozen,” relationships have warmed. “She brings a different perspective,” Mr. Cornell said.

I wondered if that perspective made them think more about themselves. Is it possible for women in their profession, where they've seen so many men put on trial for doing so many bad things to women, to not be involved in that at all?

“We've been so focused on finishing these paintings that we as women have lost sight of…” Williams began, but then stopped.

“Well, they're both dead, so you can't compare our paintings,” Cornell says. (But some people can, and have, compared them: At Trump's arraignment in Miami last year, media outlets published paintings by Rosenberg and Williams alongside those by another veteran artist, Bill Hennessy, whose sketch of Trump was criticized by some as being too glamorized.)

“He's an outsider,” Williams said. “Everybody has an opinion.”

However, it seems that only women are drawing him.

But there's something refreshing about it: The world is often male-dominated by default, politics and law even more so, so it's unique and delightful to know that this tiny corner of the universe has been temporarily elevated to new heights of importance, so completely dominated by the female gaze that the women themselves don't even realize it.