This article is part of CBC Health's Second Opinion, an analysis of health and medical science news delivered to subscribers via email every Saturday morning. If you haven't already, you can subscribe by clicking here.

A quick look at Canada's COVID-19 wastewater trends paints a confusing and unpredictable picture, with virus loads rising and falling at different times and in different cities throughout the year.

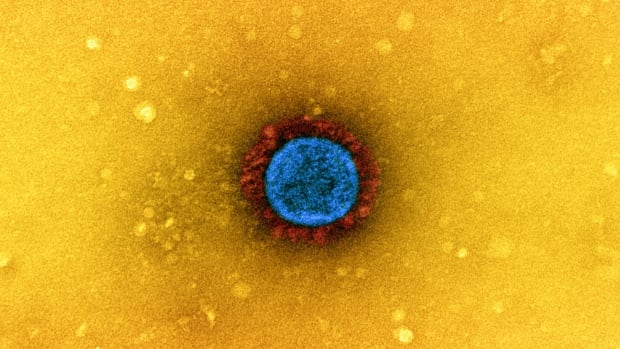

Although SARS-CoV-2 is now a well-known threat, the virus is not seasonal: It circulates actively in the background all year round, and for the fifth year in a row, some scientists are preparing for the possibility of a mini-outbreak in the summer.

This may come as a surprise to those who hoped that the virus would soon join the normal cold and flu season, with COVID infections receding during the warmer months. But we're not there yet.

“When you look at the four other coronaviruses that cause 25% of colds, there is a very pronounced seasonality,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease expert and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, “but we don't know how long it took for them to settle into that pattern.”

Meanwhile, SARS-CoV-2 is still in its early stages, and the spike protein that allows the virus to enter cells and cause infection continues to mutate at a rapid pace.

“This virus was not known to infect humans prior to 2019, so it is still under significant evolutionary pressure, especially given the immunity humans have developed,” Adalja said.

New mutant strains spread

Those closely monitoring the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 have been tracking several new variants that have become dominant in recent months.

While the JN.1 group remains the predominant strain of the virus in Canada, data from the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) shows that lineages KP.2 and KP.3, which some scientists have nicknamed “FLiRT,” after the technical term for certain genetic mutations, and LB.1 are all showing signs of increasing.

They all descend from Omicron, a variant that caused a major wave of infections midway through the pandemic. This family of viruses that is still circulating is more contagious than previous strains, and people can become reinfected multiple times because mutations in the spike protein allow it to evade protection from vaccines and previous infections.

“For the last couple of years, Omicron has been the only one we've had,” Adalja said, “and the lineage is still trying to find the best combination to infect people, so there's always some evolution going on. … The pace is still very fast, so the seasonality is not as predictable as one would hope.”

While nationwide testing results suggest that circulation of common respiratory viruses such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus has been low in recent weeks, levels of SARS-CoV-2 increased over the several weeks leading up to late May, according to the latest PHAC Respiratory Virus Report.

WATCH | Older adults still at higher risk for severe COVID infection:

New coronavirus data warns of risk to older adults who haven't yet been infected

New data from Canada suggests more than four in 10 seniors may have avoided COVID-19 infection so far, but they remain at highest risk of hospitalization and death, and researchers say staying up to date on vaccinations remains the best way to reduce that risk.

But the numbers are unclear because of limited local COVID-19 testing and varying trends in different regions: For example, roughly half of Canada's wastewater treatment plants have seen no recent change in SARS-CoV-2 infection rates, while a quarter have seen a decrease and another quarter have seen an increase.

Still, Dr. Zain Chagla, an infectious disease specialist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, said the ever-evolving versions of the virus could lead to an increase in cases in the coming months, similar to past patterns with Omicron.

“We may start to see some signs of a wave towards the end of the summer,” he added.

US health experts have warned that similar trends are on the horizon, although the number of cases is expected to be lower than in past summer outbreaks.

COVID-19 still causes hospitalizations and deaths

It's a fresh reminder that COVID-19 is here to stay, but the overall decline in infection numbers and deaths, in part due to increasing levels of immunity across the population, is making the virus easier to ignore.

Chagla said the threat has definitely decreased compared to the early days of the pandemic.

But the virus has continued to hospitalize vulnerable people through the spring and summer, and some older and immunocompromised people have died, Chagla said, and even people with built-in immunity from vaccination or previous infection can develop severe illness.

Even in 2023, a U.S. study found COVID-19 to be more deadly than the flu. The virus continues to kill people in Canada, too: 23 people died from COVID-19 in just one week in May, according to the latest PHAC data.

Adalja stressed that high-risk groups, including older people and those with other risk factors such as being overweight or pregnant, will need to continue to deal with COVID differently than those at average risk, given the highly contagious nature of the virus and how quickly immunity to infection wanes.

“It's really important for these people to stay up to date on their vaccinations,” he said.

Vaccination remains a challenge

Public apathy towards pathogens can complicate the situation.

Vaccination rates have declined over the years, with fewer than two in 10 Canadians up to date on their vaccinations, and while age is always a risk factor for severe illness, only 53 per cent of adults aged 80 and over are up to date on their shots, according to PHAC.

“They are the most vulnerable group,” Chagla said. “We can't even convince more than half of them to get vaccinated.”

The good news for those seeking a booster shot: COVID vaccines continue to be updated to better match circulating strains. This week, U.S. officials approved a fall shot based on the JN.1 lineage, and Canada is on track to fall in line with those decisions south of the border.

WATCH | How wastewater monitoring helps track COVID:

How can wastewater help monitor COVID-19?

The City of Ottawa is testing wastewater to get a better idea of how much coronavirus is in the city's water, and the project's co-lead investigator explains how it could help monitor COVID-19.

But the time lag between the emergence of new variants and the approval of adapted vaccines remains a challenge, says Dr. Nitin Mohan, a physician and epidemiologist at Western University in London, Ontario, meaning the world is always one step behind the evolution of SARS-CoV-2, which could continue to circulate and reinfect people more frequently than many older viruses.

“Hopefully one day we'll have a vaccine that can prevent infection,” Mohan said, “and I think that would be a real game-changer.”

Until that day comes, he said, no one knows how long it will take for SARS-CoV-2 to become more seasonal and predictable.

“At this point, I can probably predict more accurately when the Leafs will win the Stanley Cup.”