Did life on Earth begin in the Red Sea off the coast of Shaybarah Island in Saudi Arabia?

LONDON: It was something of a serendipitous discovery, Volker Fahrenkamp admits with a smile.

“Sometimes these things just take a bit of luck.”

Valenkamp, a professor of geology at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Thuwal on Saudi Arabia's Red Sea coast, had been traveling with a team of colleagues to take a closer look at a coastal geological phenomenon they had spotted in satellite imagery.

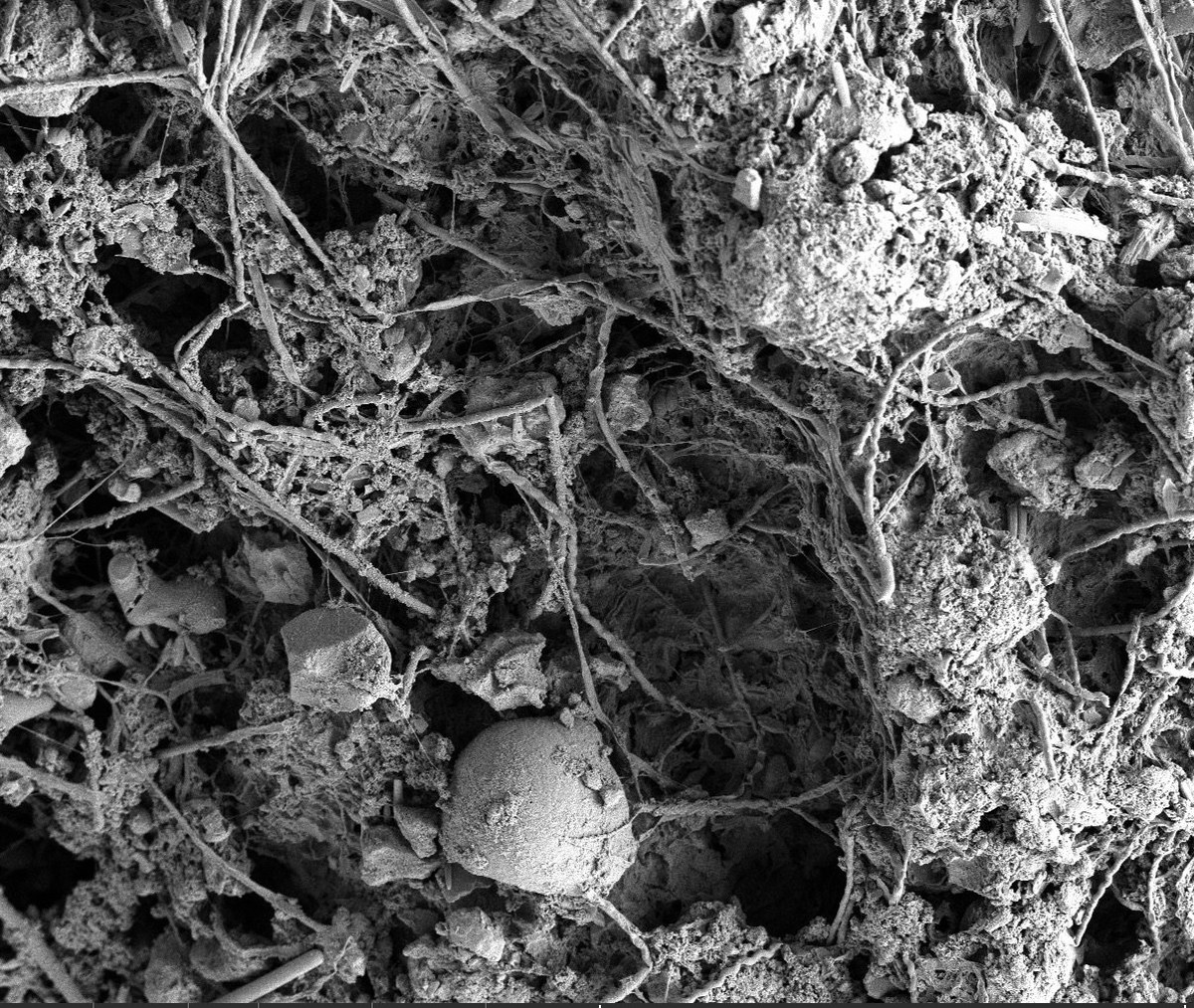

Stromatolites are layered rock-like structures made by tiny microorganisms, some of which trap sediment within their fibres. (UNSW Sydney/Brendan Burns)

So-called teepee structures, tent-like bucklings of sediments found in the intertidal zone, are valuable indicators of ancient and modern environmental changes.

The team was delighted to discover that such an example was almost on their doorstep: just 400 kilometers up the coast from KAUST, off the southern tip of Shaybara Island, best known for Red Sea Global's luxury tourist resort of the same name.

“There aren’t really many good examples where we can study how the teepee structures were formed,” Valenkamp told Arab News.

“And we found this, which is the most amazing example I know of.”

Satellite imagery showed two teepee fields in the island's intertidal zone, and after a short boat trip from the mainland in a converted fishing boat, “we landed on the island, surveyed one field and then began walking to the other field.”

And as they crossed the coastline between the two islands, “we literally stepped on these stromatolites.”

Stromatolites are layered rock-like structures created by tiny microorganisms, some of which are individually invisible to the naked eye and trap sediment within their fibers.

Stromatolites are layers that form over many years due to the action of tiny microorganisms. (Photo: Elisa Garglieri)

They live on rocks in the intertidal zone, and as they are covered and exposed each day by the tides, they slowly convert the dissolved minerals and sand grains they capture into a solid mass in a process called biomineralization.

Humans, and every other living organism on Earth that requires oxygen to live, owe their existence to tiny, so-called cyanobacteria that have been creating stromatolites for about 3.5 billion years.

Cyanobacteria were among the first life forms to emerge on Earth when the Earth's atmosphere was composed mainly of carbon dioxide and methane. They appeared about 3.5 billion years ago and had the extraordinary ability to generate energy from sunlight.

Viewed under multiple magnifications in a scanning electron microscope, this cross section of a stromatolite just 0.4 mm wide clearly shows the microbial filaments and the sediment they trap. (Photo by Elisa Garuglieri)

This process, photosynthesis, had a key by-product: oxygen. Scientists now believe that tiny cyanobacteria were responsible for the greatest event that ever happened on Earth: the Great Oxidation, which transformed Earth's atmosphere and sparked the evolution of oxygen-dependent life as we know it today.

Today, most stromatolites are just fossils. As other life on Earth evolved, stromatolites lost their foothold in Earth's oceans to competitors such as coral reefs.

Volker Wahrenkamp, professor of geology at KAUST. (Courtesy)

But in some parts of the world, “modern” living stromatolites, in Varenkamp's words, “analogs of the ancient stromatolites,” continue to grow.

“Stromatolites are the oldest traces of life on Earth,” he says. “They ruled the Earth for an incredibly long time, about three billion years.”

“Today they're part of the rock record in many parts of the world, but it's impossible to work out from these ancient rocks what kinds of microbes were involved and how they were behaving exactly.”

Numbers

• The distance from the KAUST campus to the Teepee Field is 400 kilometers.

• 3 billion years when rock-like stromatolites dominated the Earth

• Sea levels were 120 meters lower during the last ice age.

That's why the discovery of a rare living stromatolite colony like Shaybara Island is such a gift to geologists, biologists and environmental scientists.

“If we find modern examples like this, we may be able to better understand how the interactions of this microbial community led to the formation of stromatolites.”

Other examples are known, but they are mostly found in extreme environments such as alkaline lakes and hypersaline lagoons where competitors cannot thrive.

The resort on Shaybara Island. (Photo by Red Sea Global)

Previous colonies have been found in more conventional marine environments in the Bahamas — Valenkamp has visited the shoreline before — so he immediately recognized what he was walking through off Shabarra Island, but this is the first example of living stromatolites found in Saudi Arabian waters.

It's not yet clear how old these stromatolites are, “but we can narrow down the range a little bit,” Valenkamp said.

“We know that during the last ice age, sea levels here were 120 metres lower, so they weren't there 20,000 years ago. Their area was submerged about 8,000 years ago to a height of about two metres higher than today, and then about 2,000 years ago sea levels dropped again to their present level.”

Shaybara Island Resort. (Photo by Red Sea Global)

That doesn't mean the stromatolites are 2,000 years old: No one knows how long it takes for microbes to build the sediment cake, and “no one has come up with a good way to date the layers yet.”

“Tides and waves can bring sand and material from the surrounding reefs, potentially resulting in a mixture of ages. This makes it very difficult to accurately date the stromatolites and estimate their growth rates.”

So Valenkamp and his colleagues are now devising experiments in aquariums to replicate natural conditions, such as tides and alternating light and darkness, in order to grow stromatolites under controlled, easy-to-observe conditions.

Shaybara Island in the early stages of construction. (Photo by Red Sea Global)

“I honestly don't know” whether this will take a few weeks or years.

The team is also working to sequence the genes of thousands of different types of bacteria that are active in the stromatolite factories.

“The question is finding out who's there and what they're doing,” Valenkamp said.

This section contains relevant reference points arranged in the (Opinion column).

“But there are also questions about what function these bacteria have and whether they could be used in other ways, for example for medical applications.

“Scientists are now actively looking at the microbial composition of the gut to understand, for example, which microbes cause cancer and which prevent it. Microbes active within stromatolites may hold functional secrets that we don't yet know.”

The discovery also resonates with the environmental ambitions of the Saudi Green Initiative, announced by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in 2021, which, along with the Middle East Green Initiative, aims to combat climate change through regional cooperation.

The resort on Shaybara Island. (Photo by Red Sea Global)

“The discovery of the Shaybala stromatolite field has important implications not only from a scientific perspective, but also for the recognition of ecosystem services and environmental heritage in line with Saudi Arabia’s ongoing projects of sustainability and ecotourism development,” Valenkamp and seven co-authors wrote in a recent paper published in the Geological Society of America journal Geology.

In their paper, the KAUST scientists thank Red Sea Global for helping them access the stromatolite sites, which are currently being considered for protection.

For tourists relaxing in their stunning new overwater villas in Shaybarah Island's crystal clear Al Waj Lagoon, a short stroll along the beach now offers the added attraction of being transported back in time, offering a glimpse into life on Earth 3.5 billion years ago.