(Bloomberg) — Yvette Alta Rafael is full of energy and far from old, but her brittle bones, painful knees and dizziness have forced her to stop driving for fear of getting into an accident.

The 49-year-old entrepreneur is part of a generation of South Africans who have lived with HIV for decades, becoming the first to grow old with the disease after revolutionary medicines transformed a death sentence into a chronic illness.

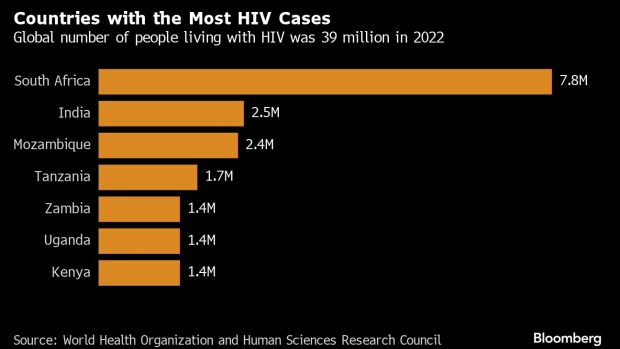

Health care costs are snowballing as the population ages, and millions are wondering what's in store for them after a key election left the country in political uncertainty and sharp disagreements over how to shore up a health care system already battling the world's largest HIV epidemic.

When Raphael, who runs a bustling clothing store in Tembisa, a town just outside Johannesburg, first learned she had HIV, she remembers thinking she'd be on treatment for the rest of her life for no more than five years. More than 24 years have passed since then, and in that time she has married, had two children and fulfilled her dream of opening her own shop.

“My biggest fear now is living for many years with the complex diseases that come with age,” Rafael said in an interview. “The government doesn't care. It's like they're saying, 'Did we save you to become a burden to us again?'”

The potential costs are staggering for a country that already spends 9 percent of its gross domestic product to fund a partly private, partly public health system, significantly higher per capita than any other country in sub-Saharan Africa.

Last month's elections saw the African National Congress lose its parliamentary majority for the first time since it took power in 1994 under former President Nelson Mandela. With no clear winner, the ANC must decide whether to form a coalition, but some of its biggest potential partners are parties with starkly different views on a range of issues, including a proposal to set up a national fund to cover the costs of universal health care for South Africans.

The longer the government takes to address the needs of people who are prematurely aging with HIV, the greater the financial losses will be in a country where 7.8 million people, or about 13% of the population, are living with the virus.

“Figuring out how to treat HIV and ageing is complex,” said Francois Venter, a professor of medicine at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, but he pointed to some first steps, such as reducing the risks of things like inflammation and cardiovascular disease.

For example, women around Rafael's age who come to the clinic to get antiretroviral drugs will also need to be evaluated for possible heart disease and screened for various types of cancer.

“It's becoming increasingly important that primary health-care clinics that also provide HIV treatment recognise that older people may have other health problems,” says Linda Gail Becker, chief executive officer of the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation in Cape Town. She also recommends monitoring balance and grip strength, which can be signs of premature ageing.

South Africa spends about $1.8 billion a year on treating people with HIV and AIDS, according to UNAIDS, which estimates that 15 percent of total government spending goes to health care, compared with 3.5 percent in India, the country with the second-highest HIV numbers.

That's not enough, Becker said. But it's hard to estimate exactly how much money would be needed. The World Health Organization is “just beginning to grapple with this problem,” he said. The Geneva-based organization declined to provide an estimate, saying in an email that it is “considering interventions targeted at older populations.”

The Ministry of Health said the government recognises the benefits of integrating non-HIV services into HIV programmes, but more evidence is needed on the cost-effectiveness of focusing on premature aging among those with the virus. The Ministry of Health is also tackling the growing burden of tuberculosis and non-communicable diseases such as cancer and diabetes.

It's not just money that's the problem, it's infrastructure. More than half of South Africans live below the poverty line, making it difficult to access regular care, especially for those who struggle to travel. Limited transport to clinics and long wait times compound the strain.

At the root of the problem lies another kind of gender disparity: The HIV virus disproportionately infects women, so many babies are born with HIV. By their mid-20s, these people have been living with the virus for decades and may already be struggling with problems that come with aging, like having trouble climbing stairs, partly from HIV and partly from the treatment.

At present, the country does not have any special services or programs at the primary care level aimed at older people (or people aging prematurely), so older people must compete for care with other patients.

How South Africa tackles premature ageing among people living with HIV could serve as an example for other countries on the continent, such as Mozambique, Uganda and Zambia, which have young populations that may live with the virus for decades.

Meanwhile, Rafael says antiretroviral treatment has allowed him to lead a fulfilling life, including traveling the world in search of new materials and styles for his shop, but it took years of campaigning before large-scale treatment became available.

In addition to running her shop, Rafael also serves as president of a national advocacy group for HIV and AIDS prevention, most recently campaigning for expanded use of pre-exposure prophylaxis, a medication that reduces the risk of contracting the virus. She believes a fight also needs to be fought to care for older people with HIV, and that fight will likely be led by women.

“I had to embarrass the government to get my antiretroviral drugs, and when I get older, I'll have to embarrass the government to get health care,” said Rafael, who struggles to find balance these days and tells her now young adult children, “It's better to have a dizzy mother than no mother at all.”

©2024 Bloomberg LP