Outside the Park Slope Food Co-op. Courtesy of Getty Images

By Mira Fox

June 13, 2024

In the checkout line of the Park Slope Food Co-op, my companion, a longtime member, bumped into a man who was stacking shopping baskets. She apologized; “We’re all in this together!” he replied cheerfully.

These are the vibes one expects at the cooperatively owned grocery store in Brooklyn famed for its steep discounts and strict member work requirements. (Everyone must work a three-hour monthly shift — stocking shelves, running checkout, managing food delivery; if you miss work you can’t shop.) In the aisles, people greet each other or recommend their favorite chocolate to total strangers. I’m not a member — I had to wear a large sticker announcing me as a “non-shopping visitor” — but that didn’t stop people from talking to me about the astonishingly cheap cheese prices.

But the harmony of the Co-op is being challenged by a group advocating for the store to adopt the principles of the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions group. The coop only stocks a handful of goods made in Israel — EcoLove shampoo and conditioner, Sabra-brand hummus, Al-Arz tahini — so the day-to-day impact of a boycott would be minimal. The symbolism, however, would be resounding.

Since this past winter, a group, wearing keffiyehs and calling itself Park Slope Food Coop Members for Palestine, has been canvassing in front of the Co-op, stopping members in line to get them to sign a petition asking the Co-op to adhere to BDS tenets, grounded in the Co-op’s values of “human rights, food justice, and positive global interdependence.” More recently, another group began canvassing under the name “Co-op members for Unity,” handing out fliers urging “the rejection of the bigotry, divisiveness and animosity created by the BDS/Israeli boycott campaign and its corrosive effects on our community.”

This isn’t the Co-op’s first go-around with the question of BDS; in 2012, the battle between the pro-BDS faction and a group called More Hummus, Please, was covered by The Atlantic and Gothamist, as well as The Daily Show, which lightly roasted the self-seriousness of anyone who believed that chickpeas could impact the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. More members than had ever attended a general meeting showed up to vote; it took an hour for the nearly 1,700 attendees to file into the room.

The referendum failed to pass back then, and, for a time, the issue subsided. But, of course, in the wake of Oct. 7, it’s back. And, to make matters even more fraught, it’s an election year — at the Co-op, I mean. Which is to say, people are acting like the access to Sabra-brand hummus at their preferred grocery store is a matter of life and death.

The ‘corrosive effects’ on the Co-op community

In theory, co-ops are the ideal of democracy, where everyone gets a say on everything; a society built on community, compromise, collaboration and shared values. But the reality tends to be less utopian; without an ultimate authority, every decision, no matter how small, can erupt into a chaos of a thousand opinions.

And though the Co-op is a beloved neighborhood shop, it’s also a huge, profitable company; it has tens of thousands of members, many of whom commute from other neighborhoods or even other states to shop and work their shifts, making it the largest member-run co-op in the country. (Other cooperative companies, like REI, do not run on member labor; they are only coops insofar as members have some limited voting power.)

Those tens of thousands of members make for tens of thousands of opinions and rules — and zealous enforcers. Each change in operations is a battle. Once, a woman tried to dodge the Co-op’s rule that all adults in a household must be members by calling her fiancé her roommate; another Co-op member found their wedding registry and called them out. Members battle over which food additives are acceptable, the volume at which music can be played over the store speakers, what kind of meat to sell — and whether the Co-op should sell meat at all. (It does, but my colleague, who has been a member since 1985, recalled a temporary compromise involving separate meat and non-meat shopping carts.)

In the letters to the editor section of the Coop’s newspaper, the Linewaiter’s Gazette, for the last several months, topics of contention included “the amplified collision of plastic” caused by the store paging system and pickle sourcing. And BDS is more controversial than any of those issues.

A Jewish woman reported feeling afraid that another member would yell at her when she bought Jerusalem-made matzo before Passover. Another mentioned a beloved tahini brand that the store carries. “Did you know it’s made by an Israeli Arab who champions LGBT rights?” she asked. The rest of the letter is devoted to a tahini smoothie recipe: “Pour into a glass, take a sip, and savor the creamy goodness of standing against BDS and supporting products that promote unity and understanding.” Many, many letters accuse the store of being unwelcoming to Jews — members wearing keffiyehs while working their shifts is a common theme — and the Gazette of antisemitism for even publishing letters about BDS.

Meanwhile, others argue that the Coop is an inherently political project, and that it has boycotted other products and countries — Coca-Cola, Nestlé, South Africa, Chile — in the past. They speak of their guilt in eating good produce from the Co-op while children in Gaza starve. Several letters accuse the Co-op of being unwelcoming to Muslims for not having Ramadan foods on display — and for fomenting anti-Muslim sentiment by printing letters that accuse BDS of antisemitism.

Things have gotten so bad that, in the same issue, the Gazette published back-to-back letters in which both a pro-Unity and a pro-BDS member reported being called a Nazi.

Bye bye bamba?

After the 2012 vote on BDS, the Co-op realized they had to find a larger space to hold controversial votes. And since the pro-BDS group began canvassing outside the Coop, the Co-op’s general coordinators — among the store’s few paid staff — announced that they’d begun to search for a venue.

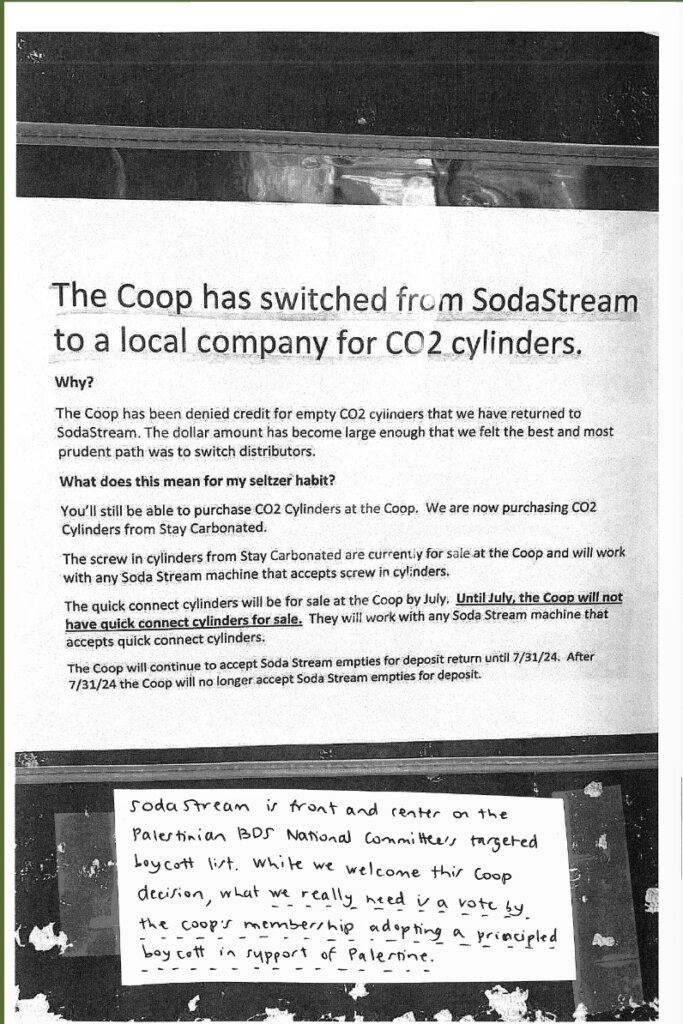

The Co-op has a sign up about SodaStream, clarifying that its absence is not related to BDS — though evidently some people disagree. The handwritten note has since been removed. Courtesy of Screenshot of The Olive Press Zine

The Co-op has a sign up about SodaStream, clarifying that its absence is not related to BDS — though evidently some people disagree. The handwritten note has since been removed. Courtesy of Screenshot of The Olive Press Zine

In the announcement, Joe Holtz, the de facto leader of the Co-op’s general coordinators, put out a firm statement in the Linewaiter’s Gazette, reassuring concerned members that the Coop had not yet taken a stand on BDS, and emphasizing the democratic process.

“The decision to boycott or not boycott must occur through the GM [general meeting] and the Board of Directors,” he wrote, underlining that the Co-op had not yet taken an official stance on the matter.

But he also expressed concern about the divisive nature of a boycott, both for its impact on the Co-op’s community, and on its bottom line.

“Regardless of the vote’s outcome, thousands of members could feel unsupported by their Co-op and may choose to withdraw their membership,” he wrote, before reminding potential voting members that “concern for the Co-op’s sustainability and continued growth for the next 50 years and beyond is also the obligation of all members.”

Some pro-BDS Co-op members took this statement as an attempt to undermine their efforts — and they don’t just blame Holt.

Earlier this spring, Brooklyn College offered the theater at the Tow Center, its performing arts venue, for the BDS vote, but the offer was withdrawn; Dena Beard, a Co-op member and the director of the Tow Center, wrote in the Gazette that she received 11 voicemails alleging violence and danger at Brooklyn College if they were to rent to the Co-op, and that senior members of the college administration were sent emails to the same effect, leading them to rescind the offer.

“I now feel much less comfortable at the PSFC,” Beard wrote. “How can the Co-op have difficult conversations if intimidation tactics like these continue to obstruct discussions?”

This set off a secondary issue: remote meetings. Co-op bylines forbid voting at them, but the pro-BDS faction is certain they would get more votes if only they could make it easier to attend.

Remote meetings have wide appeal, particularly for members who are immunocompromised or have children, but also for Co-op true-believers who see it as a way to have an engaged democratic process.

But in their Whatsapp group, the pro-Unity faction suspiciously discussed the conflation of BDS with remote meetings.

“They don’t talk to people of BDS,” one person messaged. “They are now talking of other things, like supposedly trying to get hybrid meetings for the sake of inclusivity.”

(PSFC Members for Palestine also has a Whatsapp group, but they didn’t approve my request to join and they didn’t answer any of my emails; my sense of their discussions comes from their zine which details the history of the BDS efforts at the Co-op along with an interview with a farmer from Gaza who now lives in Boston, a piece about the Tamil genocide in Sri Lanka and a page of “missed connection and want ads,” which includes a plea for a kombucha scoby.)

The politics of an election year

Amidst the ongoing BDS drama is the Co-op election for the two empty seats on its five-person board. Voting opened at the end of May and will conclude June 25; members can change their vote until then. And each side is now canvassing for their preferred set of candidates.

There are nine members running, each of whom published a statement in the Co-op’s newspaper, ranging from a few lines about loving the Co-op to a 751-word manifesto about food systems and urban farming. None of them mention Israel.

The BDS advocates are pushing for Tess Brown-Lavoie, the urban farming candidate — she also teaches at the Pratt Institute — and Keyian Vafai, a web developer and former organizer for New York state senator Julia Salazar.

The “pro-unity” faction is supporting Ramon Maislen and Sondra Shaievitz. Maislen is a construction project manager, though his additional qualifications summarized in the Linewaiter’s Gazette, include attending a “democratic school where elementary school students had votes equal to teachers.” Shaievitz is “a corporate lawyer who became an energy healer and spiritual teacher.”

The board seats are particularly contentious at this moment because, regardless of whether a referendum supporting BDS passes, the board members do not have to follow the membership’s advice. And, in fact, at a general meeting in March the candidates all said that they could “envision not following the advice of the membership in a controversial vote.”

I tried to contact several of the candidates; only Shaievitz got back to me. At first she seemed excited to talk. But as the hour of our scheduled phone call drew nearer, she backed out, asking if we could talk a month down the road instead — well after the election.

Budget barley or political produce?

Hearing about the Co-op factions, the battling letters in each week’s Gazette, the tales of tension in the aisles, you might believe that the Co-op is a stressful place. And for the most politically engaged, that seems true.

Jars for free on a cart outside the Co-op Photo by Mira Fox

Jars for free on a cart outside the Co-op Photo by Mira Fox

But when I was there this week, the vibes were friendly. I heard a woman speaking Hebrew in the aisles and no one accosted her. In several hours, I saw only one keffiyeh, despite complaints about their abundance. In the anti-BDS Whatsapp group, members who had been canvassing said many of the people they’d talked to were unaware there were even board elections. Most people, it seems, are just there for the cheap groceries.

That neutrality is, in itself, a controversial statement though. While I have many friends who are Co-op members, all were reluctant to speak on the record even if their take was far from hot. Simply saying that they didn’t really care about the political infighting as long as they continued to get discount cheese felt outre at such an inherently political and progressive store.

Still, perhaps the diverse opinions and values at the Co-op mean that maybe, just maybe, the store could lead the way in finally having a reasonable discussion about the war between opposing factions, one that doesn’t escalate into accusations and name-calling.

Bret Eynon, a historian who has been at the Co-op long enough to have retired from his shift obligations, had helped me fit my bike into the crowded parking in front of the grocery store; we have the same model of road bike and even the same panniers, though mine are yellow.

He’s supportive of the BDS call at the Co-op in part because he’s deeply invested in its communal responsibilities; “The time invested changes your relationship to it,” he said. “People learn to work together.”

Perhaps the grocery store is “not the most potent venue” for action, he said. But it gives people a chance to “practice civil discourse.”

That’s why he thinks that, despite the schism the BDS campaign has created, the Co-op might just be able to show the rest of the world how to have a reasonable conversation.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and the protests on college campuses.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO