Brad Todd is a public relations and political campaign consultant and author, with Salena Zito, of “The Great Revolt.”

I recently taught my 14-year-old son how to shave, and it reminded me of the Norelco rotary razor his grandfather gave him around that time.

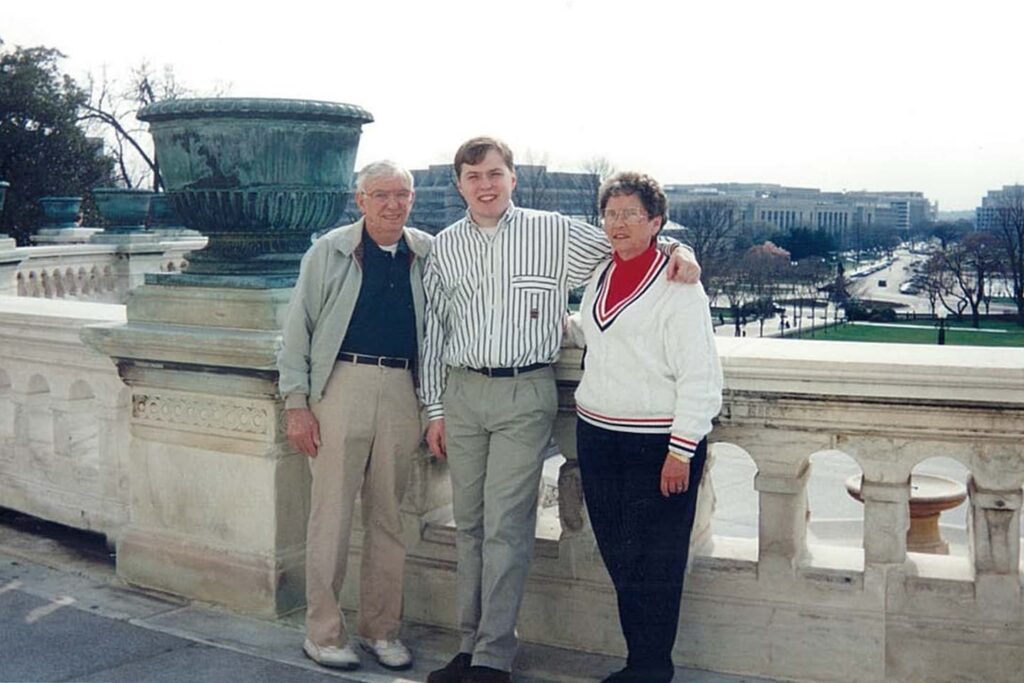

My maternal grandfather was only 44 when I was born. By that time, my father knew his strengths and was confident of his future, even in middle age. I spent the best 25 years of his life. The teachings and example he gave me, and continues to give me, are what I celebrate on Father's Day.

“Grandpa” is still with me in many ways — I still use his pitching wedge on the golf course, keep his union card in my desk drawer and show visitors to my office three of his now-antique radios — but the real evidence of Grandpa's influence can be found in many of the things I treasure.

As a baseball fan who played catcher in one of the thousands of adult baseball leagues that entertained Americans in the immediate postwar era, I grew up with my father's fandom and remain fascinated with the strategic nuances of the game. He taught me how to play golf, hold a pocket knife, and take on tedious chores.

He taught me how to pick a rib-eye steak at the butcher and how to cook it properly: seven minutes per side, per inch of thickness, no more than one second more. He cleaned his cars and trucks, inside and out. He sang his heart out in church, his arm draped over the bench and gently touching the shoulder of a loved one while he listened to the sermon.

When I was nine years old, my dad coached me in a 4-H biscuit-making contest and celebrated the blue ribbon I won. We had to settle for second place for cornbread the next year, but I still think of him every time I make either. I can still hear him say, “Just stir until the dough sticks to the fork, but no more.” At least in my memory, every activity was coached and appreciated.

As I aged into the stage of life where my father was in my childhood consciousness, I realized that my build, my hairline, and the way I walked were inherited from him, and some of my own relationships were modeled after his example.

My grandfather was a kind and loyal man, and his fun conversations with his golfing buddies allowed me to see how adults enjoyed each other's company. He respected the strong women in his large Appalachian family, and I loved them and learned from their example.

My father's good intentions for me sometimes blinded him. As a child, barely surviving on a subsistence farm, he wanted me to avoid manual labor and make a living through my brain. He tried to protect me from it. Luckily, my hard-working father understood that physical labor is a formative experience. Today, when I experience the exhausting joy of chopping wood or clearing branches, I thank my father in my heart and smile at the memory of my grandfather's overprotective attitude.

My grandfather was an accomplished bird hunter, as evidenced by the faded newspaper clippings I keep in my cigar box. He was so gifted that the manager of the nuclear weapons facility where he worked hired him as a guide. Eventually, he returned the favor by asking the big boss to hire his son-in-law, my father. With that request, the newlyweds returned home to Tennessee, and I, his future grandson, grew up in the same valley where five generations of our ancestors had grown up.

In the last years of my grandfather's life, when I was in my 20s, I finally began to see his flaws. He was so frightened by the computerization of his job that he retired a few years early. He was unreasonably annoyed when I couldn't take an afternoon off work to play golf. He hated politics and couldn't understand why I found it evangelical. Even these discoveries were helpful: if we don't see the flaws in those we admire, we might miss their humanity.

According to the National Retail Federation, Americans will spend an average of $190 on each father on Father's Day this year, well below the $254 they will spend on each mother on Mother's Day. Comedies and movies tend to portray mothers as heroes and fathers as travesties, glorifying single mothers without lamenting what is lost by not having fathers.

While I’m not sure why our culture celebrates nurturing over mentoring, I would argue that the country would benefit from also valuing men who are strong, purposeful role models. I was fortunate to have three such role models, and without their example, I would never have become the man, father, and grandfather I wanted to be.