Active legislative oversight of the executive branch is part of the nation's system of checks and balances, and Congress has the right to pursue it even when the motivations can be argued to be partisan. As journalists, we would love to hear the conversation that led Department of Justice Special Counsel Robert K. Hur to describe 81-year-old President Biden as “a caring, well-meaning old man with a poor memory.”

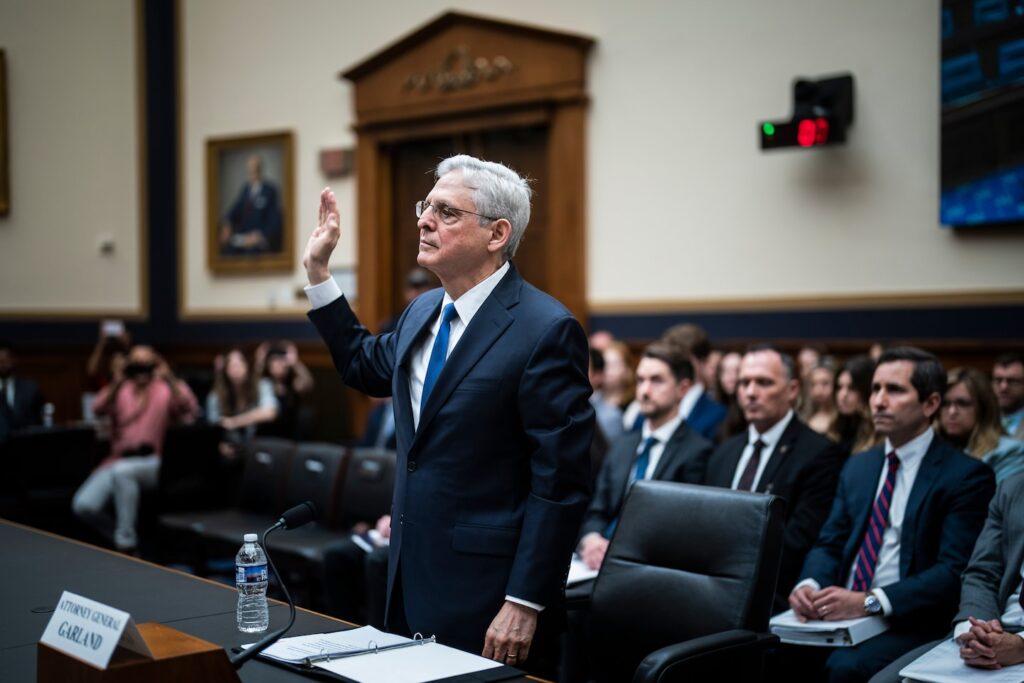

But House Republicans went far beyond that this week when they voted to hold Attorney General Merrick Garland in contempt of Congress for refusing to turn over the audio recording of the president's meeting with Hoare.

Garland sought to comply with Congress' requests in good faith, releasing 258 pages of interview transcripts and an unredacted version of Huh's 345-page report, neither of which he was required to release. Garland allowed Huh to testify before Congress for more than five hours, explaining why he believes he cannot convince a jury beyond a reasonable doubt that Biden knowingly violated the laws regarding the handling of classified materials.

The attorney general has good reason not to go further. The Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel has said that releasing recordings of interviews with people who have not been charged with crimes would undermine future high-profile criminal investigations, especially in which “the voluntary cooperation of White House officials is crucial.” At Garland's urging, Biden invoked executive privilege to block the release of the tapes, providing legal protection against criminal charges. President George W. Bush similarly asserted executive privilege in 2008, when Democratic lawmakers sought records of special counsel Patrick Fitzgerald's interviews with Vice President Dick Cheney about leaking the identities of CIA officials.

Follow this authorEditorial Board Opinion

Follow this authorEditorial Board Opinion

Biden deserves credit for cooperating with the investigation into Ho, who gave a two-day interview last October shortly after Hamas' attacks on Israel. In contrast, then-President Donald Trump refused to meet with then-special counsel Robert S. Mueller III and only answered written questions about his activities before taking office. Biden also deserves credit for not invoking executive privilege to block the release of Ho's report or records.

Republicans argue that Garland's release of the transcripts waived executive privilege over the audio, to show that good deeds always pay. But Garland needs to balance the competing interests of disclosure and fairness and draw the line somewhere. Perhaps the Justice Department should have offered to let Republicans listen to the tapes in secure conditions and with recording restrictions. Such a compromise might have worked if the president's critics in Congress were truly interested in the facts, rather than, say, the release of embarrassing audio clips.

On Wednesday, all Democrats and one Republican voted against holding Garland in contempt. Rep. David Joyce, R-Ohio, said the attorney general “basically complied” with the House subpoena. “As a former prosecutor, I cannot in good conscience support a resolution that would further politicize our justice system in order to score political points,” Joyce said. “Enough is enough.”

The contempt vote is symbolic, but by referring the issue to Garland's own department, which declined to prosecute the attorney general on Friday, the move downplays what should be serious steps to address real obstruction of justice by the administration. House Republicans held Attorney General Eric Holder in contempt in 2012 for refusing to turn over records related to the botched gun-tracing film “The Fast and the Furious.” Five years ago, House Democrats held Attorney General William P. Barr in contempt for withholding documents related to the Trump administration's effort to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census.

Ironically, Garland, who still has a judicial temperament even though he is no longer on the bench, is perhaps the least partisan of his cabinet. He appointed Republican Harr to investigate Biden and authorized special counsel David C. Weiss to pursue a criminal case against Hunter Biden. Federal prosecutors won three felony convictions against the president's son just one day before the House of Representatives indicted Garland in contempt for defending the president.

Garland described the contempt vote as “the latest in a long line of attacks” on his department's independence. He worries that Trump and his allies' demonization of law enforcement puts investigators and prosecutors at risk. On Thursday, for example, federal authorities charged a Texas man with threatening to kidnap and kill an FBI agent involved in the Hunter Biden case. In this heated election season, elected officials in every branch of government need to find ways to defuse tensions.