When my son Nick was born, I, like any parent, wanted my children to be healthy and happy. But when Nick became addicted to heroin and methamphetamines as a teenager, my dreams changed. I wanted him to get drug-free and stay that way. As his drug problem worsened — he spent 10 years using dangerous combinations of potentially deadly drugs — my hope for him became very simple: just survive.

He did, and my gratitude for his life is now at the center of our relationship. He is here. The past and its aftermath are all secondary.

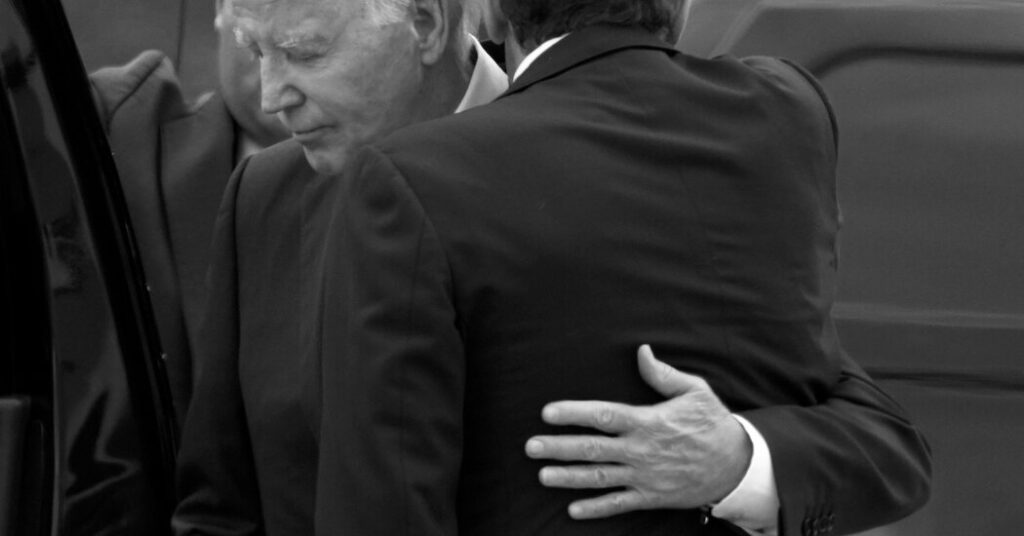

I was thinking about another father whose son had a severe substance use disorder; he survived and is now in recovery. Americans have strong opinions about President Biden and his son, Hunter, and that's understandable. The president has asked us to consider reelection, and Hunter was recently convicted of three felony counts for lying on a federal firearms application in 2018. This is a father-son relationship unlike any the American electorate has ever grappled with.

But much of the debate over Joe Biden and Hunter Biden seems to me to be very wrong, because it reflects a deeper misunderstanding of the relationship many parents have with their children who have substance use disorders.

Hunter has been described as a “headache” to his father, with one commentator saying he is paying a “political price” for his troubles and that his father is “too deferential” to his son.

All of this is fine in the political world. But when Americans consider President Biden's thoughts and feelings about his son, they shouldn't assume that Biden is dwelling on whether their interests conflict or whether Hunter is a political headache. Hunter didn't make life easier for his father, but people with substance use disorders generally don't make life easier for their loved ones. That doesn't mean that parents of addicted children only see them that way.

We don't know if Biden thinks of his son only in political terms, but it's probably not. A parent who thinks they might lose a son or daughter never forgets the pain. There are at least some indications that Biden felt that anguish in Hunter's 2021 memoir, “Beautiful Things,” which describes escalating drug and alcohol abuse. Hunter writes about a time when the president came to visit (accompanied by security) and he was “drinking to avoid the physical pain that came with not drinking.”

“I thought I'd be lucky if I passed out,” he wrote, the last thing he wanted to see was his father, but there he was, at the front door.

“He seemed horrified by what he saw,” Hunter wrote. “He asked me if I was OK, and I said of course I was.”

“'I know you're not okay, Hunter,' he said, studying me and glancing around the room. 'You need help.'

“I looked into my father's eyes and saw a look of despair and fear.”

As the father of a child struggling with drug addiction, I know exactly how the President feels. I felt that despair. I felt it so many times searching for my son on the streets, when he broke into our home and friends' houses to steal checks and credit cards, when he ran away and relapsed after we finally got him treatment. I felt the fear when Nick was rushed to the emergency room and the doctor called to tell me he might have to amputate his arm because it had become infected from IV drug use. Another time, the doctor called and said, “Scheff, your son is here. Please come here. We don't know if he'll survive.”

At Al-Anon meetings, parents and loved ones of people struggling with addiction are presented with three “C's”: You didn't cause it, you can't control it, and you can't cure it. Two of the three “C's” are incontrovertible. I couldn't control or cure my son's addiction. (God knows I tried.) But no matter what the meeting leaders said, part of me believed Nick's addiction was my fault. If only his mother and I had stayed together. If only I had been stricter, or looser. The “what ifs” were endless.

This struggle is only known by parents who have a substance abuse disorder. Only those in the same situation can understand the unique horror of addiction and the fear, shame and self-blame that come with it.

A father's love does not absolve Hunter, and the president has said he will not grant a pardon. Some parents wipe their hands of their drug-addicted children. They lock the door, figuratively and sometimes literally. As I sat there, disgusted by Nick's relapse and embarrassed and appalled by his shameful behavior, I wanted to do that but never could. Apparently the president cannot do that either. Or chooses not to.

For President Biden, for me and for others in this predicament, the fact that Hunter is alive and facing this problem (apparently one day at a time, without relapse) may mean everything. The president will leave it to the courts to decide, but his love will not waver. He will leave it to the voters to decide, but his pride will not waver.

Only parents with children struggling with addiction can understand the pride we feel for our children in recovery. Nick has been sober for 13 years and is building a full, meaningful life that was never imagined when he was using.

Biden has also repeatedly said he is proud of his son. The president issued a statement after the guilty verdict was read last week.

“I'm president, but I'm also a father,” he said. “Jill and I will always have our love and support for Hunter and our entire family, no matter what.”

David Sheff is the author of Beautiful Boy: A Father's Journey Through His Son's Addiction and is currently writing a biography of Yoko Ono.

The Times is committed to publishing diverse letters to the editor. We want you to tell us what you think about this story and others. Here are some tips: Email us at letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp. X And threads.