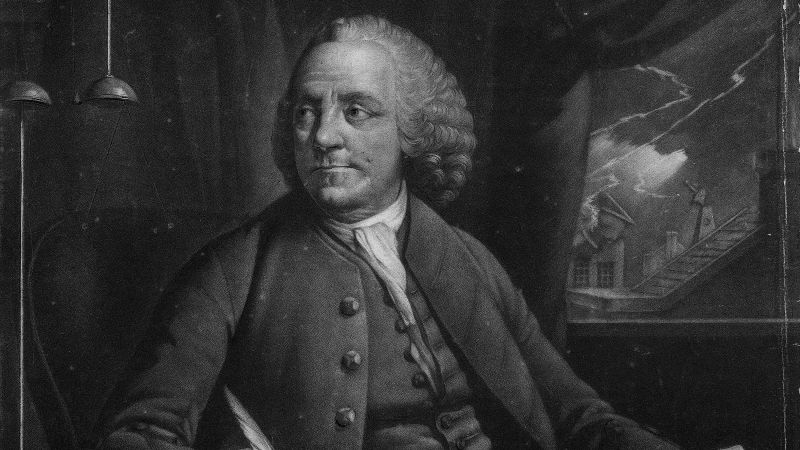

Editor's note: Eric Weiner is a former NPR international correspondent and the author of five books, including his latest, “Ben and Me: The Search for a Founder's Formula for a Long and Effective Life.” The opinions expressed in this op-ed are Weiner's own. Read more opinions on CNN.

CNN —

The 81-year-old politician has faced a mix of praise and derision as he embarks on a pivotal chapter in his life. He moves slower and speaks more softly, but his mind is clear and his courage is intact.

That statesman is not President Joe Biden, but Benjamin Franklin. In his 80s, he was by far the oldest delegate to the Constitutional Convention. Many scoffed at him behind his back, doubting whether he could handle the task, but he proved them wrong. He made a huge contribution, helping to set the tone for compromise and forging the breakthrough that saved the day and the young republic.

There is no better model for an older statesman than Franklin, whose last third of his long life (he lived to be 84) was by far the most interesting, while the first two-thirds were thoroughly fascinating.

He accomplished the most and changed the most during his final act, perhaps playing colonial golf in Florida. This was when Franklin the Loyalist became Franklin the Rebel and later Franklin the Abolitionist. This was when he charmed the French into supporting the American cause and ensured the success of the Revolution.

What gets forgotten in the debate about how old one is to occupy the White House is the fact that chronological age says very little about a person. It's not age that matters, it's what kind of old one is: cranky old or happy old, resigned old or bold old. Franklin was in a category all his own. He certainly didn't become president, but he proved that age is no barrier to wise, inspired leadership.

It's not the age that matters, but the type of age.

Eric Warner

Franklin was 70 when he helped edit the Declaration of Independence. His most significant revisions came early on. Jefferson's original draft had read, “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable, that all men are created equal.” Perhaps with Franklin's boldest stroke, he struck out “sacred and undeniable” and replaced it with “self-evident.” We hold these truths to be self-evident.

This may seem like a minor revision, a more concise restatement of the same idea, but it is much more. Jefferson's original wording appeals to religious authority. By revising the passage to read “self-evident,” Franklin appealed to a different and what he believed to be a higher authority: human reason. Franklin understood something that Jefferson, less than half his age, did not.

Franklin kept himself busy, and when seeking public office he always followed the motto: “Never ask, never refuse, never resign.” He always had to be important and useful; he needed to be needed. He gave little thought to death. “It is my motto to live as if we were going to live forever,” he once said. “Only with that feeling can we exert the efforts necessary to accomplish a useful purpose.”

Recent research supports Franklin's approach. A 2014 study published in the Journal of Psychology and Aging found that many people become happier as they age, even in the face of adversity, but only if they have a flexible sense of self. When it comes to matters of the head and heart, Franklin was remarkably agile, that rare man who gets more agile with age, not less. At age 69 and working in London, he went from English Loyalist to American rebel. Even into his 80s, he continued to change his mind on important issues, like slavery.

Consider again the role he played in the Constitutional Convention of 1787. At 81 years old, Franklin was old enough to be a father to everyone else and a grandfather to most others. When Franklin first argued for the unity of the colonies in 1754 (the so-called Albany Plan), he was 48 years old; James Madison was 3 years old.

Although Franklin suffered from many physical ailments, including gout and kidney stones, and sometimes had to be carried to the convention in a palanquin, the Founding Father's mind remained sharp, likely honed by regular exercise, especially swimming and his invention of an early version of Sudoku, the magic square. Convention director William Pierce said Franklin possessed “the mental activity of a youth of 25.” Manasseh Cutler, who visited the elderly Franklin at his home, was impressed by “the perfect serenity of his manner, and the irrepressible freedom and happiness which permeated every part of him.”

But it wasn't all smooth sailing. Franklin's age made him the object of both respect and ridicule. Younger representatives praised his past achievements but not necessarily his current contributions. Some dismissed his ideas out of hand, while others ridiculed him behind his back. Ageism is not a 21st-century invention.

It wouldn't be the first or last time that Franklin was underestimated. Though he didn't play a decisive role in shaping the Constitution (that role was left to younger delegates like James Madison and Alexander Hamilton), he managed to calm passionate emotions and bring warring factions to compromise. “The Old Magician,” as John Adams called him, often accomplished this with a sleight of hand. At one point, Franklin suggested opening each session with a prayer; an unlikely suggestion that went nowhere, but it did provide some much-needed breathing room.

Throughout Philadelphia's sweltering summer of 1787, Franklin worked tirelessly, albeit quietly and behind the scenes, embodying 17th century lawyer John Selden's maxim that “He who governs most, makes least noise.” Contrast this with our assumption that the louder the better.

As the convention deadlocked, Franklin helped craft the Great Compromise (also known as the Connecticut Compromise): one legislative body, the House of Representatives, would be determined by population, and the other, the Senate, would be determined by the states, with each state having an equal number of seats in the Senate. This plan, supported by Franklin, saved the crisis and the fledgling nation.

At the end of the convention, with its outcome still uncertain, Franklin made an impassioned plea for something seldom commended today: doubt. Franklin had doubts about whether the Constitution, drafted in the previous months, was the best possible one, but he intended to sign it anyway. “I have lived a long life, and have seen many instances in which better information and deeper consideration have compelled me to change my opinions, even on important questions, when opinions which I once held to be correct have proved otherwise.” Franklin went on to say that as he grew older, he was more inclined to question his own judgment and to “have more respect for the judgment of others.”

Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter

Franklin's message is as relevant today as it was in 1787. Even more so. It is easy to doubt other people's opinions; what's hard is to doubt your own. Doubt everything, including your own doubts, Franklin advised, and don't get too attached to your intellectual castles, which may be made of sand. What he once said about scientific theories also applies to political theory: “How many beautiful systems we build, only to be soon compelled to destroy them!”

It's easy to question other people's opinions, the hardest part is questioning your own.

Eric Weiner

Franklin pointed out that the hallmark of a mature democracy is not just the institutions and policies it establishes, but its readiness to modify those institutions and policies to suit new circumstances. That is why Franklin called the new U.S. Constitution an “instrument” rather than a document or blueprint. Its value and usefulness are precisely as good as the character of the people who use it. This is an important observation, and one that only occurs to those who have been alive for a few years.