David Friend, an editor at Vanity Fair magazine, is the author of The Naughty Nineties: The Decade That Unleashed Sex, Lies, and the World Wide Web.

In the past few months, the US has been rocked by two high-profile trials. In one, Donald Trump was found guilty of 34 felony counts related to a scheme to bribe porn actresses to keep quiet about sexual encounters during the 2016 election (Trump's sentence is scheduled for July 11). In the other, President Biden's son Hunter was found guilty of three felony counts for providing false information on an application to purchase a firearm. During the trial, jurors heard testimony from a woman Hunter Biden met at a strip club who said the defendant smoked crack cocaine (sentencing is expected by October).

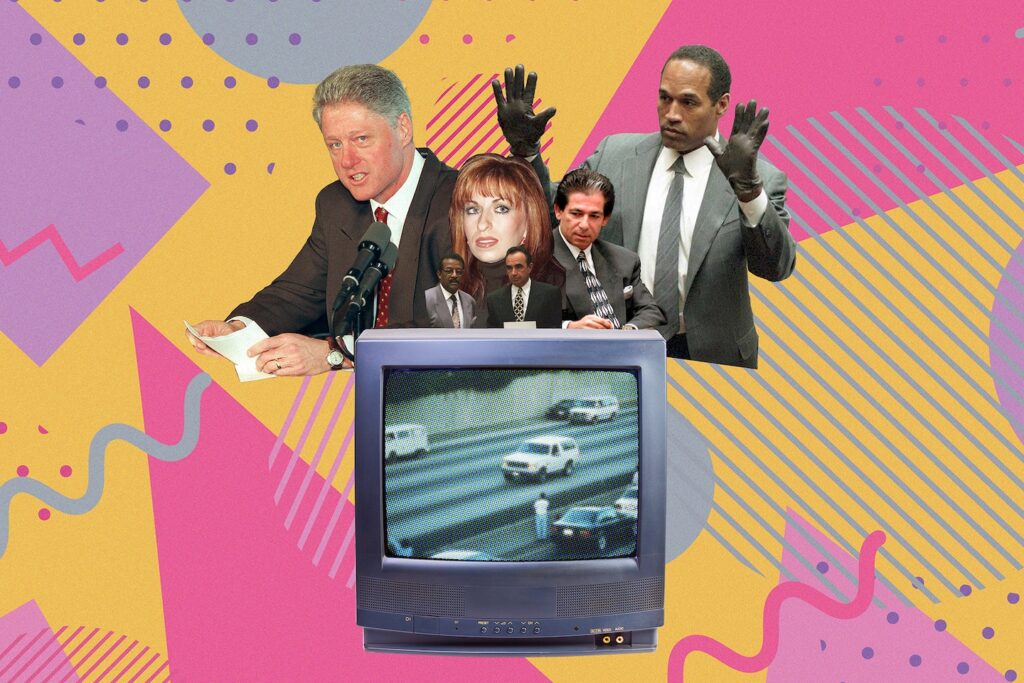

Strippers and porn stars haven't figured much in the story of America's First Family since the founding of the republic. Neither have hush money or cocaine addictions. But here we are, and I believe much of the current uproar dates back to exactly 30 years ago, when two other legal dramas were sweeping the nation. I firmly believe that two eerily simultaneous news events in May and June of 1994 unleashed a tsunami of sex, scandal, shamelessness and outright lies whose effects are still rippling throughout the culture.

On May 6, 1994, former Arkansas government official Paula Jones filed a sexual harassment lawsuit against President Bill Clinton. Jones claimed that three years earlier, when Clinton was governor, he had naked before her in a Little Rock hotel room, a charge he denied. The lawsuit pitted Jones and her far-right supporters against the president and his powerful legal and political team, with Clinton's allies trading insinuations to discredit Jones and undermine her allegations. The showdown marked the beginning of a five-year saga of prosecutorial abuse, political fistfights, and immorality that culminated in the president's impeachment by the House of Representatives and acquittal by the Senate in 1999.

On June 17, 1994, six weeks after Jones filed his lawsuit, former football star O.J. Simpson attempted to escape a police encirclement in a white Ford Bronco in a “slow-speed car chase” broadcast live before an estimated 95 million viewers. After turning himself in to authorities, he was charged with the stabbing deaths of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ronald Goldman. For many, the ensuing legal battle, which ended with Simpson's acquittal, became the first real-world reality TV show, a soap opera that dominated the nation for more than a year.

At the time, these two legal battles were so unusual that they were treated as cultural anomalies. Coverage of the Jones case, which seems hard to believe now, was initially deemed too salacious (a president accused of sex crimes?) to merit mainstream media coverage. It was largely dismissed as a nuisance lawsuit, relegated to talk radio, tabloids, and the murky corners of a new realm called the World Wide Web. But by 1998, two new news and opinion outlets, the Drudge Report (launched in 1995) and Fox News (launched the following year), had rapidly escalated the Jones case into front-page news, with a special counsel appointed to investigate Clinton's potential misconduct (and soon sex).

When it was revealed that the president was having an affair with a White House intern, the news took on an overtly sexual overtone. The Starr report alone was 7,793 pages long, taking forever to download from the Internet, and was so sexually explicit that journalist Renata Adler described it as “a ton of demented pornography.” The whole pitiful spectacle was best summed up by Philip Roth, who wrote in his novel The Human Stain: “It was the summer when the president's penis occupied everyone's minds and life once again embarrassed America with its shameless impurity.”

By then, Simpson's “trial of the century” had already begun to turn TV news into 24-hour entertainment. The courtroom drama, with its oddball ensemble of misfits, sharply suited lawyers, and publicity-hungry people, seemed more like a circus than a murder trial. There were testimonies about rampant drug use, briefs chronicling sexual adventures, and defense lawyer kayfabes that sounded like something out of a pro-wrestling textbook. There was judge Lance Ito, houseguest Brian “Cato” Kaelin, and Brown Simpson's Akita, also named Cato. Simpson's ex-girlfriend Paula Barbieri, Brown Simpson's friend Faye Resnick, and one juror even made a cameo in Playboy. The nightly parade of TV “experts” (Greta Van Susteren, Geraldo Rivera, a Stetson-wearing Jerry Spence) became the cable TV equivalent of Weegee: a smorgasbord of voyeurism and bloodshed. And let's not forget Simpson's lawyer friend, Robert Kardashian, who became the patriarch of a clan that would become a swarm of reality TV stars.

In and out of the courtroom, the actors performed for the cameras. The trial, which resulted in a limited, forever binge-watchable series, shattered notions of legal ethics in the American mind, and even reality itself. As author Jonathan Schell has written, the Simpson-Clinton drama turned out to be a beta test for a “new media machine” that, as Schell puts it, “championed a trivial matter (sex and lies about sex) into a major event (the impeachment of a president and damage to the constitutional system)…” [and] “It may have fatally tilted the balance of forces that was newly at stake — the balance between fantasy and reality,” Schell believes. He believes the Bronco chase in June 1994 was a turning point: “At that moment, virtual reality and old-fashioned reality became inseparably fused in some new way.”

At the time, the cases against Clinton and Simpson were unusual, eerie spectacles set in the midst of mundane public life. By 2000, both presidential candidates, George W. Bush and Al Gore, had campaigned on the idea of restoring “normalcy” to a country ravaged by the loss of “values.” They failed miserably. But in the three decades since this story began, the bizarre has become commonplace. Themes that had been pushed to the fringes of culture have somehow come imperceptibly to the forefront. In 2024, we can barely make out the plot as a barrage of scandals, unimaginably bad choices, and social media memes come and go, each more outrageous than the last.

In September 2023, for example, a video surfaced of Rep. Lauren Boebert (R-Colo.) sitting in the audience of a Denver theater during a performance of the musical “Beetlejuice” and appearing to grope the genital area of her male companion. A month later, camera footage surfaced of two men engaging in sexual activity in a hearing room in Sen. Hart's office building. These dumpster fires continue. Last month, presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (a habitual cheater, former heroin addict, and alleged proponent of conspiracy theories) claimed that a doctor he examined in 2010 found dead parasites in his brain. And in May, two lawmakers engaged in a schoolyard-style verbal exchange on the House floor. After Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) criticized Rep. Jasmine Crockett (D-Texas) by saying, “I think your fake eyelashes are ruining what you're reading,” Crockett fired back, criticizing Greene's “bleach blonde, lanky, masculine body.”

It doesn't stop. Even outside the halls of Congress, pop culture is saturated with explicit sex, from Miranda July's novel All Fours (whose tales of lust and fantasy are driving book clubs wild) to Netflix's third season of Bridgerton (depicting a sexy Regency-era orgy). And it seems like every other month, a teacher or professor loses their job from academia because, in their off-hours, they happen to be posting DIY adult images and videos on their OnlyFans accounts. Shame on you. No, it's not.

There are myriad reasons why this sleaze and poverty is so prevalent, but fundamentally there are three causes.

First, our chief executives have become increasingly adept at offering master classes in deception over time. This has been going on since well before the 90s, from Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard M. Nixon (who lied about Vietnam), to the consummate actor Ronald Reagan (who never mentioned AIDS during his first term), to Clinton (who was impeached for lying under oath), to George W. Bush (who lied about “mission accomplished” in Iraq and that FEMA Director Michael D. Brown had “done a great job” in responding to Hurricane Katrina). It was only a matter of time before this long era of lying produced a leader like Donald Trump, whose falsehoods so often exceed reality that they recall Mary McCarthy’s famous line to Lillian Hellman: “Every word she writes is a lie, even the ‘and’ and the’.” For large swaths of the population, outright lying in the short term (as a way to achieve long-term goals) had become a tactic, a way of behaving, a kind of accepted ethical habit.

Second, since Jones and Simpson, we have lost our collective sense of shame. As Christopher Hitchens wrote in a 1996 Vanity Fair column, tabloid culture has somehow made America “a country in which it is almost impossible to shame.” Narcissists began to inflate their own value in society in entirely new ways. Haters began to be consumed by fear and loathing, often taking pleasure in degrading those they considered worse off, or more often than not, lucky. Shame became archaic, a vestige of a bygone era of civility and decency. To quote the wise Hitchens, “There is a good reason why the words 'shameful' and 'shameless' define the same behavior. You know you have behaved shamefully if you have subjected others to unnecessary inconvenience and embarrassment. If you don't understand this, you won't know you have behaved shamelessly.”

Finally, speaking of the Clinton-Simpson reality show circus, there was reality TV itself. Since 1992, when MTV's “The Real World” aired as the first modern reality show, the genre has fully infiltrated the bloodstream of people's behavior. Since then, the mass audience called America has become a horde of innate exhibitionists. Their public and private behavior, and even their sex lives, have been unintentionally shaped by the tropes and rituals of such shows: rehearsed indignities, false seductions, and the belief that, as Shakespeare had already said, all life is a stage. And with the rise of social media in the early 2000s, the deal was solidified. In the 90s, there were only a few people, a few dozen at most, at the white core of the madness. Now, billions of so-called users seek followers, the virtual merges with the real, and the biggest and most flashy car crashes get the most likes. We used to hesitate to exercise a minimum of courtesy before watching a car crash. Now the fools are rushing in en masse, and our better angels have already fled.

Perhaps Stormy Daniels said it best, when explaining why she stayed in contact with the man who she claims urged her to watch a documentary about shark attacks after their affair: “I wanted to maintain that relationship because I wasn't sure if I was going to be on The Apprentice yet. It would have been amazing.” Who could argue?