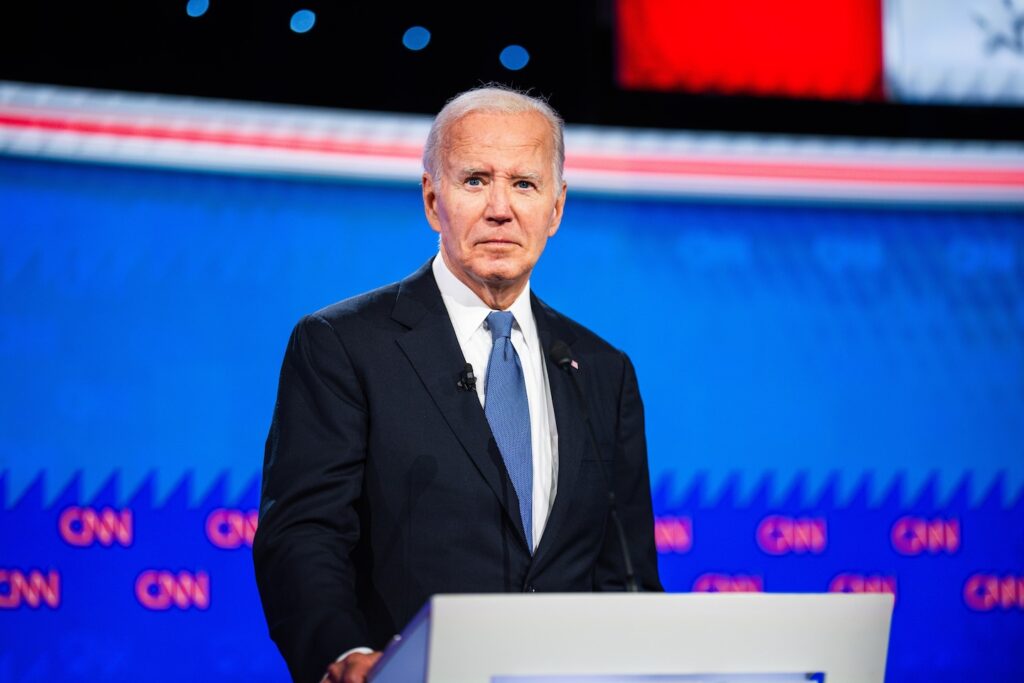

President Biden's dismal debate performance has sent Democrats into a state of panic, leading to growing calls and personal expectations for the president to step down.

The harsh reality for Democrats is that trying to replace Biden at their August convention may be even more dangerous than clinging to the weak horse they're riding.

The president and his advisers have been adamant that he intends to continue the campaign. Indeed, a much more powerful candidate showed up at a rally in Raleigh, North Carolina, on Friday. “I came to North Carolina because I'm going to win this state in November, and if I win here, I'll win the election,” he declared to a sold-out, cheering crowd.

Privately, campaign officials have begun an effort to convince wavering donors that while the president's onstage performance was lackluster, he still has what it takes to beat Donald Trump.

If Biden leaves office, Vice President Harris would likely announce her candidacy immediately, but given Biden's unpopularity, other candidates will likely come forward, perhaps from a field of capable and attractive Democratic governors such as Gavin Newsom of California, Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, JB Pritzker of Illinois, Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania and Roy Cooper of North Carolina.

Follow this authorKaren Tumulty's opinion

Follow this authorKaren Tumulty's opinion

This scenario would free up the 3,894 convention delegates previously tied to Biden (well above the 1,968 needed for the nomination) to be drawn from a broad base of party activists, union leaders and local party officials, rather than being controlled by a handful of party leaders.

The convention will take place from Aug. 19 to 22, but the Democratic National Committee is already planning a “virtual roll call” by Aug. 7, a step necessary to certify that his name will appear on Ohio's ballot this fall.

As I've written before, Democratic Party rules technically allow the nominating process to be restarted at the convention, and people will no doubt point to history as an example of a last-ditch effort. In late March 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson, accepting the reality that his chances of reelection were dire, announced that he would not seek or accept the party's nomination.

But things were very different then: Only 14 states and the District of Columbia held primaries, and in most parts of the country, party officials like mayors, governors, borough presidents and local chairs held real power.

They regrouped around Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who won the Democratic nomination without ever seriously competing in a primary, and whose convention in Chicago that year turned traumatic and violent.

Humphrey's defeat in November led to the modern system of state-by-state primaries and caucuses. The Republican Party also revamped its process. Conventions became a formality. Not since the epic 1976 Republican primary battle between Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan had the nomination not been predetermined.

But what if that doesn't happen this year? Heavyweights like former presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton may have some influence over the party's choices, but those smoke-filled rooms are long gone.

The new forces of social media and big money are further dismantling old power structures.

Can we really hope for a consensus candidate to emerge from this chaos? And even if we do, will that candidate, who has never experienced the rigors of a national primary, be good enough to carry the Democratic banner across the finish line in November?

Biden may have gone down in history as the most successful one-term president in modern history, perhaps ever, and he may have been credited with saving the country from Trump. But he chose to put the country through this in an election year when not only the White House but also control of the House and Senate were at stake.

The party also made a choice: it turned a blind eye to Biden's increasingly obvious mental and physical failings. But America knows what it saw on Thursday night. Now, the only real option left for Democrats is to pray for a miracle.