In the decade following the financial crisis, the problem for the world economy was a lack of spending. Worried households paid down debt, governments imposed austerity, and prudent companies hired from a seemingly limitless pool of workers while holding back investment, especially in physical strength. Now, consumption is coming back explosively as governments stimulate the economy and consumers allow themselves to be extravagant. The surge in demand is so strong that supply is struggling to keep up. Truck drivers are paid their contracts, swarms of container ships sit off the coast of California waiting for ports to clear, and energy prices are soaring. The oversupply of the 2010s has given way to a scarcity economy as rising inflation scares investors.

Please listen to this story. Enjoy more audio and podcasts on iOS or Android.

What browser are you using?

The immediate cause is covid-19. The roughly $10.4 trillion global economic stimulus package triggered a fierce but lopsided backlash as consumers spent more than usual on goods, stretching global supply chains that had dried up investment. Demand for electronic products has surged during the pandemic, but a shortage of microchips embedded in electronic products has hurt industrial production in some exporting countries such as Taiwan. The spread of the Delta variant has led to the closure of some clothing factories in Asia. In the rich world, immigration is declining, economic stimulus is filling bank accounts, and there is a shortage of workers willing to move from unpopular jobs like selling sandwiches in cities to high-demand jobs like warehousing. ing. From Brooklyn to Brisbane, employers are scrambling for redundant workers.

But scarcity economies are also the product of two deeper forces. First is decarbonization. The switch from coal to renewable energy has left Europe, and the UK in particular, vulnerable to a natural gas supply panic, with spot prices rising more than 60% at one point this week. Rising carbon prices in the European Union's emissions trading scheme are making it difficult to switch to other, dirtier forms of energy. Wide swaths of the country are facing power outages as some provinces rush to meet tough environmental targets. Currently, rising transportation costs and prices of technological components have led to increased capital investment to expand production capacity. But at a time when the world is moving away from dirty forms of energy, the incentives for long-term investment in the fossil fuel industry are weak.

The second force is protectionism. As our special report explains, trade policy is no longer written with economic efficiency in mind and punishes geopolitical opponents from imposing labor and environmental standards overseas. They pursue a variety of goals.

President Joe Biden's administration confirmed this week that President Donald Trump's tariffs on China (which averaged 19%) will remain in place, only promising that companies will be able to apply for exemptions (good luck with the battle with federal bureaucrats). Around the world, economic nationalism contributes to scarcity economies. The UK's truck driver shortage has been exacerbated by Brexit. India is running out of coal due to a misguided attempt to cut fuel imports. After years of trade tensions, cross-border corporate investment flows have fallen by more than half compared to global GDP since 2015.

All of this may seem eerily reminiscent of the 1970s, when many places faced lines at gas pumps, double-digit price increases, and slowing growth. However, this comparison has its limitations. Half a century ago, politicians got their economic policies badly wrong, fighting inflation with wasteful policies like price controls and Gerald Ford's “Whip the Inflation Now” campaign to encourage people to grow their own vegetables. Although the Federal Reserve is currently debating how to predict inflation, there is consensus that central banks have the power and duty to control inflation.

For now, uncontrolled inflation seems unlikely. Energy prices should fall once winter is over. Over the next year, vaccines and new treatments for covid-19 should become more widespread, reducing disruption. Consumers are likely to spend more on services. Fiscal stimulus will be tapered in 2022. Biden is struggling to pass a huge spending bill through Congress, and the UK plans to raise taxes. The risk of a housing collapse in China means that demand could fall and even return to the slump of the 2010s. And increased investment in some industries will ultimately lead to increased production capacity and improved productivity.

But don't get me wrong. The deeper forces behind the scarcity economy persist, and politicians can easily slip into dangerously wrong policies. Someday, technologies such as hydrogen should help make green power more reliable. However, this will not solve the shortage right away. If fuel and electricity costs rise, there could be a backlash. If governments fail to secure adequate green alternatives to fossil fuels, they may have to address the shortage by relaxing emissions targets and returning to more polluting energy sources. Governments therefore need to plan carefully to deal with higher energy costs and slower growth due to emissions cuts. Pretending that decarbonization will bring about a miraculous economic boom is bound to lead to disappointment.

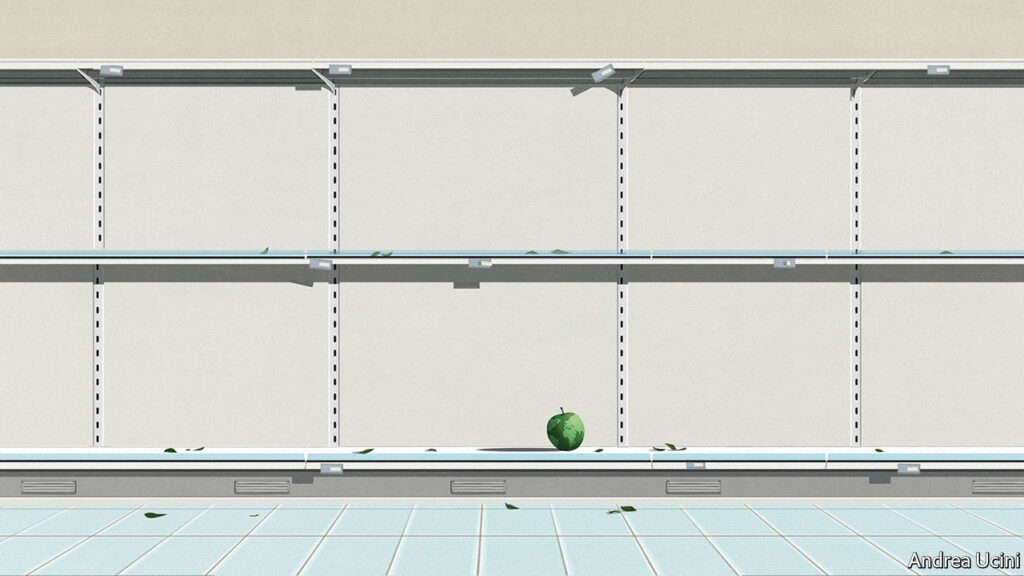

Scarcity economies may also make protectionism and state intervention more attractive. Many voters blame the government for empty shelves and the energy crisis. Politicians can evade responsibility by blaming capricious foreigners and weak supply chains, or by touting false promises of greater self-reliance. Britain has already bailed out fertilizer factories to maintain supplies of carbon dioxide, an input to the food industry. Governments are trying to argue that labor shortages are a good thing because they increase wages and productivity across the economy. In reality, barriers to immigration and trade will, on average, lead to a decline in both.

Wrong lesson at wrong time

Disruption often leads people to question economic orthodoxy. The trauma of the 1970s led to a welcome rejection of big government and crude Keynesianism. The risk now is that economic distortions could lead to a denial of decarbonization and globalization, with devastating long-term consequences. That is the real threat posed by the scarcity economy. ■