Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up for Global Economy myFT Digest and get it delivered straight to your inbox.

What will happen to the world economy? We'll never know the answer to this question. A series of big and mostly unexpected things happened during those 10 years for him. These include the great inflation and oil shocks of the 1970s, the disinflation of the early 1980s, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of China in the 1990s, and the financial crisis of the 1990s. High-income economies in the 2000s, pandemics in the 2020s, post-pandemic inflation, wars in Ukraine and the Middle East. We live in a world of conceivable and obvious consequential risks. Some wars, such as wars between nuclear powers, can be devastating. The difficulty is that it is nearly impossible to predict low-probability, high-impact events.

A must-read book

This article was featured in the One Must-Read newsletter, which recommends one noteworthy article every weekday.Sign up for our newsletter here

But we also know some big features of the world economy that are not really uncertain. These should also remain in our hearts. Here we will introduce five of them.

The first is demographics. All of the people who will become adults in 20 years have already been born. People who will be over 60 years old in 40 years are already adults. Mortality rates could skyrocket, perhaps due to a terrible pandemic or world war. But unless such a catastrophe occurs, we have a good idea of who will be alive decades from now.

Some characteristics of our demographic are very clear. One is that fertility rates (the number of children born per woman) are falling almost everywhere. In many countries, especially China, birth rates are far below replacement levels. On the other hand, the highest birth rate is in sub-Saharan Africa. As a result, their share of the world's population could jump by 10 percentage points by 2060.

These demographic changes are driven by longer lifespans, changes in women's economic, social, and political roles, urbanization, higher costs of raising children, improved contraceptive methods, and changes in people's focus on what they value in their lives. This is the result of a change in the way we determine whether there is. It seems that only a huge shock can change this situation.

The second feature is climate change. Perhaps current trends will improve over time. But while greenhouse gas emissions have barely stabilized, the buildup of these gases in the atmosphere continues to increase, and the world continues to get hotter. There is no doubt that this situation will continue for a long time. If this were to happen, temperatures would certainly rise by well over 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, which we are told is the upper limit of reasonable safety. We need to do more to reduce emissions. But adaptation will also require significant investment.

The third characteristic is technological progress. Advances in renewable energy, particularly the declining cost of solar energy, are one example. Progress in life sciences is a different story. However, in modern times, the information and communication technology revolution has become central to its development. In The Rise and Fall of American Growth, Northwestern University's Robert Gordon argues that the breadth and depth of technological change has almost inevitably slowed since the Second Industrial Revolution in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. argued with power. For example, transportation technology has changed little in half a century.

Nevertheless, the changes in information processing and communication have been astonishing. In 1965, Gordon Moore, who later founded Intel, said, “As the number of components per circuit increases, unit cost falls, so by 1975 economics meant that on a single silicon his chip he could as many as 65,000 We may need to pack in some components.” That was it. But surprisingly, Moore's law of the same name still holds true nearly half a century later. In 2021, the number of such components was 58.2 billion. This allows for incredible data processing. Moreover, in 2020, 60 percent of the world's population used the Internet. This will require further changes in the way we live and work. The development and use of artificial intelligence is the latest example.

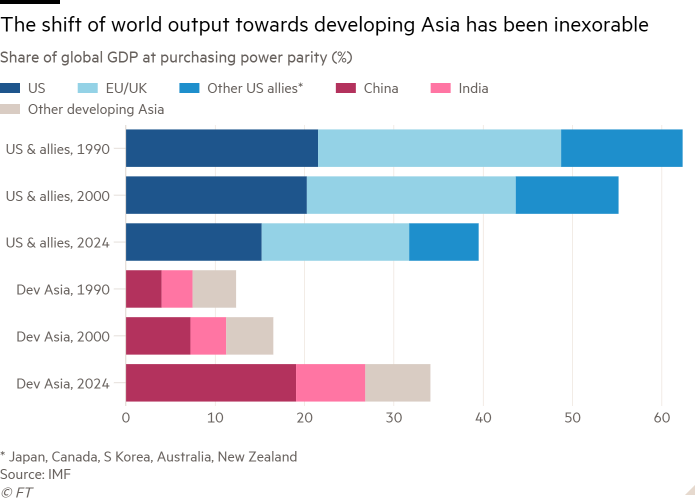

The fourth characteristic is to spread know-how around the world. The developing regions of the world that have proven most adept at absorbing, utilizing, and further developing such knowledge are East, Southeast Asia, and South Asia, which contain approximately half of the world's population. . Developing Asia also continues to be the world's fastest growing region. Given the ability and opportunity to catch up, there is no doubt that this situation will continue. The center of gravity of the world economy will continue to shift towards these regions. It will inevitably cause political change. In fact, it already is. China's rapid economic rise is a great geopolitical fact of our time. In the long term, India's rise is likely to have a major global impact.

The fifth characteristic is growth itself. According to the latest work by the late Angus Maddison and his IMF, the world economy has grown every year since his 1950s, with the exception of 2009 and his 2020. Growth is an inherent feature of our economy. The World Bank's recent Global Economic Outlook predicts that 2024 will be a “disastrous juncture, with the weakest five-year global economic growth performance since the 1990s, and one in four developing countries.” People are now poorer than they were before 2024.” pandemic”. Nevertheless, even during this period of shock, the global economy has grown, albeit unevenly across countries and peoples, and over time. We is not moving into an era of global economic stagnation.

Easily overwhelmed by short-term shocks. But we must not let the urgent overwhelm our awareness of what is important. There are great forces in the background, such as those mentioned above, that will reshape our world. You need to pay close attention to impacts while improving your ability to deal with them.

martin.wolf@ft.com

Follow Martin Wolf on myFT. twitter