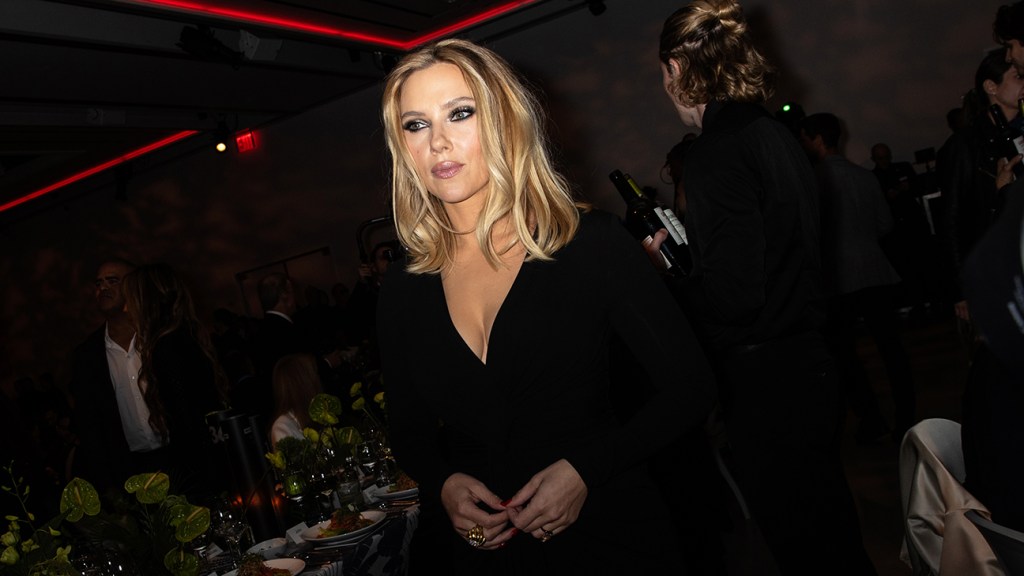

scarlett johansson

Lexi Moreland/WWD/Getty Images

Artists were the first to sue. The authors then launched a barrage of lawsuits and subsequent publications against generative artificial intelligence companies. As battle lines are drawn over the use of AI tools in Hollywood, the next group of creators will open new fronts in industry-defining legal battles against AI companies over the use of copyrighted works and personal data. I might become an actor. Power chatbots that mimic humans.

On Monday, Scarlett Johansson threatened legal action against OpenAI for allegedly copying and imitating her voice after the company refused to license it. According to the actress, OpenAI asked her to be one of the voices in their latest AI system called “Sky.” She said no, but that didn't stop CEO Sam Altman.

“When I heard the public demo, I was shocked, outraged, and in disbelief that Mr. Altman was pursuing a voice that was so eerily similar to mine that my closest friends and the press could not tell the difference,” she said in a statement.

Johansson said the similarity was intentional, noting that Altman tweeted “Her,” a reference to her role as an AI assistant who develops a close relationship with humans. He said he was referring to. She hired a lawyer and wrote her two letters to OpenAI, instructing it to detail the process that created the “Sky” voice. Both letters mentioned in Johansson's statement, which she wrote herself, were sent after Altman's company staged demonstrations and filed multiple potential legal claims. , a person familiar with the matter told The Hollywood Reporter.

“If it wasn't for the letter, they wouldn't have done this,” the source said. “This wasn't just, 'What's going on over there?' [letter]. This was much more aggressive and powerful. ”

OpenAI has released Sky, but fears of litigation are creeping in as the company faces legal challenges surrounding the foundation of its technology.

The legal threat comes after Berkeley-based AI startup LOVO filed a proposed class action lawsuit in New York federal court accusing the company of profiting from stealing the voices of actors and A-list talent, including Johansson. This is what follows. Ariana Grande and Conan O'Brien. This is believed to be the first lawsuit against an AI company over the use of likenesses to train AI systems, and alleges indiscriminately combing through a trove of copyrighted works and data to power the technology. This shows that the rift between creators and companies is growing.

For SAG-AFTRA, OpenAI's failure could not have come at a better time. AI services that allow users to clone members' likenesses without consent or compensation are proliferating. The union has blitzed lawmakers who have asserted the federal right of publicity in the absence of any federal law covering the use of AI to imitate an actor's likeness. A patchwork of state right-of-publicity laws has filled the gap, but OpenAI's alleged theft of Johansson's voice highlights the limitations of the current legal landscape.

“This case highlights the importance of protecting your voice in the age of AI. The ease of cloning your voice is no longer science fiction, it's science fact,” a SAG-AFTRA spokesperson said. “Whether you're a professional performer wanting to protect your career or an individual wanting to protect their word, federal protections are needed now more than ever.”

SAG-AFTRA was involved in introducing three bills to Congress, including two bills that would create voice and publicity rights at the federal level and one bill that would criminalize non-consensual deepfake sexual images. Unions are also working to block the use of AI in production pipelines. New York state is considering a bill that would ban tax credits when AI is used to replace labor. In March, Tennessee passed the first bill banning the use of AI to imitate human voices and making violations a criminal offense.

The union argues that using members' likenesses to train AI systems without their consent is a violation of their rights. This issue is likely to be decided by the courts.

The incident, which pits A-list celebrities against OpenAI in public, creates tension between tech companies expanding into Hollywood and creators who fear being displaced by tools they may have unintentionally helped develop. This shows that the gap is getting deeper and deeper. Mistrust of AI companies is growing, with many believing Altman's company is not operating with integrity.

Mira Murati, chief technology officer at OpenAI, said in a livestream in March that the voice assistant was not intended to sound like an actress. And before Johansson went public with her incident, the company said in a blog post that it “doesn't believe AI voices should intentionally imitate the unique voices of celebrities.” It omitted information that the company had refused a voice license.

OpenAI executives have repeatedly refused to answer questions about whether the company's text-to-video conversion tool Sora was trained on YouTube videos, and Murati said the company uses “publicly available and licensed data.” He said he used it. It also does not disclose the materials used to train its AI systems, a decision made to maintain a competitive advantage over other companies. The company has been sued by several authors for using copyrighted books, most of which were downloaded from the Shadow Library site.

There's a distinctly Silicon Valley ethos to OpenAI's actions: asking for forgiveness, not permission.

“If Ms. Johansson could do that, imagine what she would do to a 23-year-old budding screenwriter,” says Justin Nelson, a lawyer for the writers who sued OpenAI and Microsoft. Although she moved to Hollywood, she still does not have her resume as an actress. ”

Legal experts consulted by THR say Johansson is unlikely to sue now that OpenAI has dropped Sky, which would effectively mean the injunction was granted without filing a lawsuit. , if OpenAI is involved in a lawsuit, it will face a tough battle in court.

Bette Midler's lawsuit against Ford over a series of commercials dubbed the “Yuppie Campaign” that used singer impersonators to imitate the singer's voice may be instructive. Like Johansson, Midler was asked to sing for an advertisement, but he declined. Ford then hired her voice imitators to sing her songs in commercials. After the broadcast, she was told by “many people” that it “sounded exactly the same” to them, according to her court filing.

Midler appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals after a federal judge overseeing the case granted summary judgment to Ford, saying he had no right to prevent her from using her voice. The court ultimately found that the singer's voice defined her identity and that Ford benefited from it. This ruling establishes rights to non-copyrightable identifiers, such as audio, when those features involve individuals known for their functions.

At the heart of the court's order was Ford's motivation for hiring a Midler impersonator. Questions the judge asked included why the company asked Midler to sing when his voice was worthless and why it directed impersonators to imitate singers.

Intellectual property lawyer Pervi Albers said OpenAI's solicitation of Johansson's services is critical to determining whether the company violated her publicity rights. “It was clearly the voice they were looking for,” she added. “They wanted to capitalize on her husky voice.”

Bottom line: It might be okay if Johansson's voice wasn't used in training for “Sky,” as long as the goal was to capture her performance in the Spike Jonze movie.

The lawsuit could also advance publicity rights, privacy rights and possibly federal trademark claims over the likelihood that consumers would be confused into believing she was affiliated with OpenAI. A person familiar with the matter said the letter contained “references that go beyond mere publicity rights claims.”

If Altman was attempting to recreate Johansson's performance on film, Sky may also have had a stake in the rights to Annapurna, the company that produced Her.

The specter of AI looms over the entertainment industry. A survey of 300 leaders across Hollywood released in January found that three-quarters of respondents said AI tools are helping their companies eliminate, reduce, or consolidate jobs. ing. It is estimated that nearly 204,000 jobs will be negatively impacted over the next three years.

Paul Sky Lehman, a voice-over artist with more than a decade of experience suing AI startups, said his work has decreased by about 50 percent since last year. He stressed that the problem was not only fewer job opportunities, but also “a decline in my reputation.”

“My voice is literally in places I don't want to be, saying things I wouldn't say to brands I don't work with,” he added.