I was unfair to Ted Stevens, as I think many of us were.

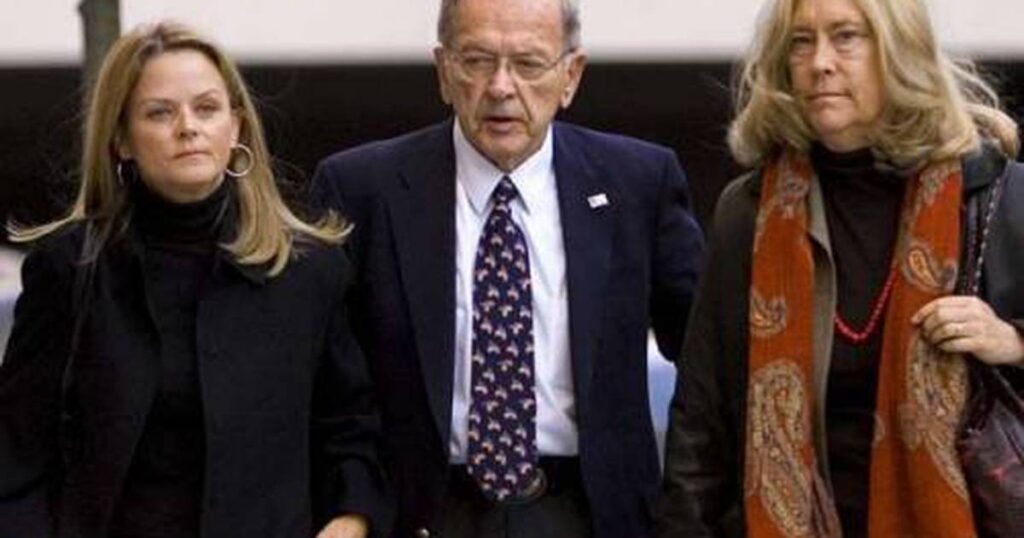

In 2008, after 40 years as a U.S. senator, a jury convicted him of a felony for failing to disclose gifts he had received. Eight days later, he narrowly lost reelection. The following year, the conviction was overturned after prosecutors failed to present evidence to the defense.

This sounded like a technicality — Stevens had indeed received the renovation work for free but had not reported it, and the bribe-giver, Bill Allen, had been caught on video bribing other Alaskan politicians. The impression left was that Stevens was exonerated, not that he was innocent.

The judge in the case ordered an investigation into the Justice Department lawyers who prosecuted Stevens, which was not completed by the time Stevens died in a plane crash in 2010 and Allen was released from prison in 2011. By the time the 500-page report was finally released in 2012, it was old news.

But I recently had a chance to read the special counsel's report, as well as another 500-page report on the case, and realized I'd been wrong all these years.

Stevens was innocent. I judge the evidence to be that Bill Allen set him up and the prosecutors went along with it.

And it got me thinking about the excessive power of prosecutors, whose personal integrity and impartiality are our only real defense against the criminal justice system destroying our lives.

So what does that tell us about the prosecution of Donald Trump? I'll write about that in my next column.

Let's go back to 2002. Renovations at Senator Stevens' Girdwood ski cabin were going awry. Stevens was too busy to keep up and barely used the cabin. His friend Bill Allen, who used the cabin a lot, took over the renovations, along with staff from his giant oilfield services company, Veco.

New Jersey Sen. Bob Torricelli had just been in trouble for accepting gifts, including watches, rugs and Italian suits, and Stevens mentioned the matter when he wrote Allen twice that fall asking him to provide invoices for all his work. He told him to give the invoices to a friend in Girdwood who was managing the projects.

Stevens also emailed his assistant with instructions on how to pay for the work. Bill Allen, the site manager, also believed invoices had been submitted. Stevens' wife, Katherine, paid all invoices the couple received.

But Bill Allen hadn't sent in the bill.

In 2003, the FBI launched the Polar Pen investigation into corruption in the Alaska Legislature. In 2006, agents captured Bill Allen on video in a Juneau hotel room bribing Republican lawmakers to block an oil tax increase. Allen then changed his tune and agreed to testify against those he had corrupted in exchange for immunity for his family and company, allowing him to keep his vast fortune.

Allen offered to testify that he had worked for free at the Girdwood home, something that Stevens had not reported. But Allen was a questionable witness. In addition to his many political crimes, he was also a pedophile. He had given gifts and money to a 15-year-old girl and her family, had sex with her repeatedly, and then had the girl lie about it in a sworn deposition.

Federal prosecutors knew about inducing perjury in 2004 but covered up and denied it to protect Allen's credibility as a witness, and they also asked the Anchorage Police Department to step aside from investigating Allen for sexually abusing a minor in 2004 because of a separate incident.

In 2008, as prosecutors were preparing to indict Stevens, they received copies of a memo Stevens had sent to Allen in 2002 that mentioned Torricelli and requested invoices, as well as emails he sent to his assistant. The lawyers' internal emails indicated concern that this evidence could harm the case. The emails supported Stevens' account that he had requested invoices, believed he had received them, and paid any invoices he received.

The lawyer and FBI agents met with Allen and asked him about Torricelli's memo. He said he didn't remember it. Conveniently, the agents and lawyers forgot about the meeting and lost the records, so the memo was never made public. They also intended to keep the foreman's testimony about the invoices secret.

Allen had not yet been sentenced on many of the charges and knew his sentence would depend on his cooperation with prosecutors. An FBI agent made it clear to Allen that he was upset that his lawyers had not remembered the Stevens memo. The agent told Allen, “You better think about it, or remember, what you did with this Torricelli memo from Ted.”

Allen changed his testimony shortly before trial, saying he “remembered” that Stevens had told him to ignore the note, saying it was merely a “clean up my ass” message.

When Allen testified in court, the defense was shocked; they had never heard the story before. On cross-examination, Stevens' lawyer asked Allen when he first told the prosecution this “clean up” story. Allen said it had been his story all along. The prosecution, who knew it was a lie, said nothing. In fact, they repeated it in their closing arguments.

After his arrest, government lawyers offered up a series of elaborate excuses (many more than I've mentioned here) for the many mistakes they made against Stevens. These excuses are far less plausible than Stevens' explanation for why he didn't report the gifts. The special counsel found that the prosecutorial misconduct was intentional.

But their motives were not political: Republican George W. Bush was president when Stevens was indicted, and it was President Barack Obama's attorney general who acquitted Stevens.

Allen became one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in Alaska through lies, cheating and bribery. When he was caught, he made a deal to avoid punishment. I imagine he deliberately hid the invoices to smear Stevens.

The strategy worked: Allen served less than two years in prison, was never charged with a sex crime, and lived a prosperous life for more than a decade after he was released from prison.

The only remedy left is to correct our memories of Ted Stevens and remember that when police and prosecutors lack integrity, they can convict almost anyone.

Next: The indictment of Donald Trump is much bigger than Trump himself.

• • •

Opinions expressed here are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Anchorage Daily News, which welcomes a wide range of viewpoints. To submit an article for consideration, email commentary(at)adn.com. Submissions of under 200 words may be sent to letters@adn.com or click here to submit from any web browser. Read our complete guidelines for letters and commentary here.