You're reading the Today's Opinions newsletter: Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox.

The country's first election campaign sex scandal

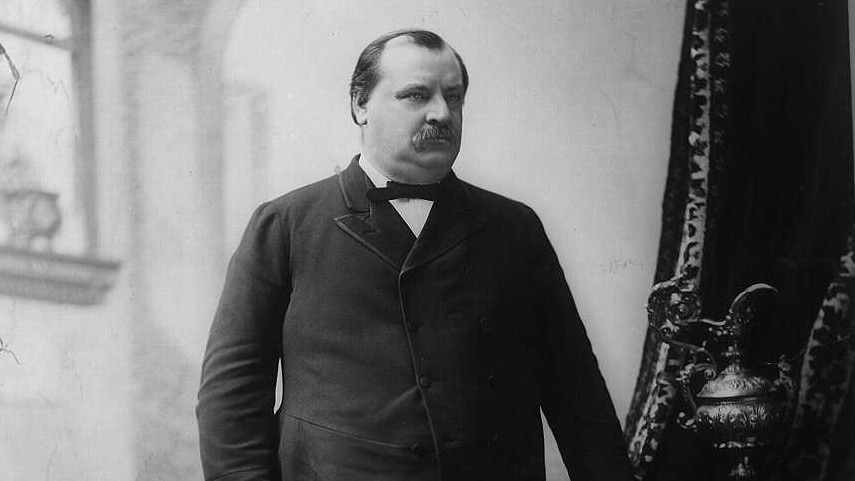

How does a presidential candidate survive a sex scandal? Take the example of Grover Cleveland, the womanizer that's on everyone's mind these days.

As the trial of one high-profile candidate caught up in wrongdoing (yes, that's right) nears its end, historian C.W. Goodyear takes us back to America's first real sex scandal during a presidential campaign, which began in 1884 with reports that Cleveland had fathered a child out of wedlock.

Goodyear writes that in those days of tight restrictions, this should have been disastrous for Cleveland, but a confluence of factors meant that it wasn't.

First, his Democratic opponent in Cleveland was particularly weak and gaffe-prone. (Ugh.) Second, he benefited from a deeply polarized electorate seduced by third parties. (Doubly ugh.)

But what really turned things around for Cleveland, according to Goodyear, was his “extraordinary response to an extraordinary crisis” — his honesty, or at least the perception of honesty. By candidly disclosing details about his illegitimate child, Cleveland “performed an astonishing act of political jiu-jitsu,” Goodyear writes, so much so that “Tell the Truth” eventually became his campaign slogan.

Sadly, radical honesty is where the resemblance to the scandal-ridden candidate of the day ends. If a jury acquits Donald Trump in his hush-money trial, it won't be because of a bold confession of the truth. Indeed, Dana Milbank writes that the former president's defense ended “with absurd, easily debunked lies” that suited the occasion.

Trump's lawyers want the world to believe that the October 2016 release of the Access Hollywood recordings was no big deal, that everyone is seizing on damaging news here and there to cover it up, and that “conspiracy” is just another way of saying “teamwork.”

Will the jury support it? Will the rest of the country support it? It could determine whether Cleveland retains another notable honor: being the only president to serve nonconsecutive terms.

Segregation’s Long Shadow

This month marks 70 years since Brown v. Board of Education mandated the end of racial segregation in public schools. It feels like a long time ago, until you realize that many people are still alive who remember that tumultuous transition to racial segregation.

Sociology professor and author Khalida Brown interviewed hundreds of residents of Harlan County, Kentucky, the heart of the Appalachian coal mining region, to document an oral history of how the Supreme Court decision changed their lives.

In conversations with people in their 80s, 70s, and even 60s, she recounts how de facto segregation lasted longer than official policy (“I looked through one of the yearbooks and saw a bunch of awards,” one interviewee says, “and all the winners were white kids, our senior year of high school”) and how segregation itself created “deep hurt and anger among the black students” who loved their school and their teachers, many of whom quickly lost their jobs.

These complexities come across particularly clearly in the interview snippets Brown includes, in which integration pioneers speak in voices about costs that still resonate today, and none of them are entirely far-fetched.

From a column by Catherine Rampell, who argues that nearly everything Americans believe about the economy is wrong, and that it's everyone's fault.

The inescapable reality is that the economy is indeed doing well. The U.S. economy is nearly unique among the rest of the world in not only growing but exceeding post-COVID growth expectations. Not since the Nixon administration has unemployment been this low for this long.

So what's going on? First, ordinary people and economists have different definitions of key terms. For ordinary people, “inflation” means “prices are still too high” and “recession” means “prices are still too high, and by prices I mean gasoline.”

But that only explains part of the problem. The biggest problem, Katherine writes, is that people are “more likely to click on, watch, and share content that provokes anger.” We're desperate to feel angry about the economy, and about anything else, really.

Maryland's Larry Hogan is an Independent, which means that in a more practical sense, the candidate for U.S. Senate is a Republican. But that doesn't mean he's not an Independent. He is an Independent. I mean, an Independent. He just has an “R” next to his name. (But in parentheses!)

In his latest column, Mark Fisher asks what voters should think about the former governor's “efforts to shed partisan labels.” Mark writes that when Hogan led Maryland, he could nudge partisan supporters or “push people aside.” He ran his own campaign and successfully defended abortion rights while still receiving praise from his police peers.

But as a senator, he points out, that's just “one vote out of 100,” so how will independence survive?

Chaser: Perry Bacon writes that race and education are the major causes of America's partisan divisions. The real causes are geography and religion.

Barkha Dutt saw the Indian elections as merely a reaffirmation of Prime Minister Narendra Modi's power. But Indians' growing preference for everyday governance over Hindu nationalism could change that. Max Boot and foreign policy analyst Sue Mi Terry write that one bright spot in global politics is the strengthening of ties between the US, Japan and South Korea, which will be key as the Chinese threat rises. George Will is amused by the Federal Trade Commission's “antitrust worriers”' focus on maintaining the accessibility of luxury handbags. Is this the work of Republican operatives trying to make progressivism look ridiculous?

It's goodbye. It's a haiku. It's… “goodbye.”

(Unless you're Grover Jr.'s mom)

Have a newsy haiku of your own? Email me with any questions, comments or concerns you may have. See you tomorrow!