When you see someone trying to hit a softball, you don't think they're going to swing at their own head. Apparently, Dario Amodei has never played softball. At the Bloomberg Technology Conference on May 9, the founder and CEO of Antropic, which makes the AI assistant Claude and is valued at $15 billion, was asked an upbeat question at the end of the session: “Explain why people should be excited about artificial intelligence, not scared.” All he could answer was, “10 out of 10, I'm excited. And 10 out of 10, I'm worried.” His spokesman probably went home after receiving a tough 10 out of 10 question.

Most AI CEOs respond that, if you take a more optimistic view, the glass might explode. Elon Musk believes there's a good chance that AI will destroy humanity, which is why his company, X.ai, is doing everything in its power to stop it. OpenAI president Sam Altman believes artificial intelligence can solve some of the planet's toughest problems, but at the same time, it's creating enough new ones that he's proposed scrutinizing top AI models with an equivalent of UN weapons inspectors.

Unfortunately, all of this is bogged down in the most silly of places. Acknowledging that AI is equally as promising and dangerous, and that the only way out of the Möbius strip is to keep building it until good finally wins out or not, is Wayne LaPierre’s domain. The former president of the National Rifle Association has incorporated liability avoidance into his sales pitch, declaring that “the only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is to stop a good guy with a gun.” I don’t think the AI giants are as bad as LaPierre, and there are national security arguments for why they should stay ahead of China. But are we really going to lumber into an arms race that enriches AI makers while absolving them of responsibility? Isn’t that almost too on-brand, even for the US?

These concerns wouldn't be as big if the first big AI crisis were a hypothetical event in the distant future, but there is a day circled on the calendar: November 5, 2024. Election Day.

For over a year, FBI Director Christopher A. Wray has been warning of a wave of election interference that would make 2016 look cute. In 2024, no respectable foreign adversary needs an army of human trolls. AI can spit out literally billions of pieces of misinformation that look and sound real about when, where, and how to vote. AI can also easily customize political ads to individual targets. In 2016, Donald Trump's digital campaign manager Brad Parscale spent hours customizing small thumbnail election ads for groups of 20 to 50 people on Facebook. It was a miserable job, but an incredibly effective way to make people feel noticed by the campaign. In 2024, Brad Parscale is software, available to any chaos agent for a fraction of the cost. There are increasing legal restrictions on advertising, but AI can create fake social profiles and aim them squarely at individuals' feeds. Deepfakes of candidates have been around for months, and AI companies continue to release tools that make all this material faster and more convincing.

Follow this author Josh Tyrangiel's opinion

Follow this author Josh Tyrangiel's opinion

About 80% of Americans believe some form of AI misuse is likely to affect the outcome of the November presidential election. Director Wray has placed at least two election crimes coordinators in each of the FBI's 56 field offices. He has urged people to look more carefully at media sources. In public, he is a symbol of calm. “Americans can and should have confidence in our electoral system,” he said at an international cybersecurity conference in January. Privately, an elected official familiar with Director Wray's thinking told me that the director faces the paradox of a middle manager: heavy responsibility but limited power.[Wray] “The director continues to raise issues, but he doesn't play politics and he doesn't make policy,” the official said. “The FBI enforces the law. The director says, 'Ask Congress where the law is.'”

Is this becoming one of those angry rallying cries against Congress? Well, in a way it is, because the Senate has spent a year blabbing about the need to balance speed with thoroughness when regulating AI, and then failed to deliver on either. But stick with me for the punch line.

On May 15, the Senate released a 31-page AI roadmap that immediately invited friendly fire. “The lack of vision is a blow,” declared Alondra Nelson, Biden’s former acting White House director of science and technology policy. The roadmap contains nothing to compel AI makers to step up or to help Wray. There are no content verification standards, no mandates for watermarking AI content, let alone digital privacy laws that would criminalize deep fakes of voices or likenesses. If the AI industry thinks it should be both arsonists and firefighters, Congress seems happy to provide them with matches and water. But we can at least get a taste of how Sen. Todd Young (R-Indiana), a self-described member of the Senate’s AI gang, summarized the abdication of responsibility: “If ambiguity is necessary to reach an agreement, we embrace ambiguity.” Dalio Amodei, you’re free to go.

You know the Spider-Man meme? The one where two Spider-Men point at each other in confusion, accuse the other of being a conman, and the criminal runs away. This version is like 2.5 times worse, because while AI companies shrug and Congress praises ambiguity, it's social media companies that are spreading most of the misinformation. In comparison, it's actually not that bad.

No, it really was. It was Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg who initially denied the impact of Russian misinformation on the 2016 election, calling it “pretty crazy.” But a year later, Zuckerberg admitted he was wrong and launched what security and law enforcement officials at Meta and other platforms call a kind of “glasnost.” Both sides recognized the risk of failure and found ways to work together, often using their own AI software to detect anomalies in posting patterns. Then they shared their findings and weeded out bad content before it spread. The 2020 and 2022 elections were not just proofs of concept, they were successes.

But all this cooperation predated the AI boom, and it all ended last July. Mursi v. Missouri, a lawsuit brought by Republican attorneys general of Louisiana and Missouri, argued that federal communications with social media platforms to remove misinformation constituted “censorship” and violated the First Amendment. Was the lawsuit an act of political vendetta, motivated by a misconception that social media leans left-leaning? Of course. But how coercive communications between social media platforms and, say, a president with narcissistic personality disorder need not be partisan. U.S. District Judge Terry Doughty sided with the plaintiffs and issued a preliminary injunction, which was upheld by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

In March, Sen. Mark R. Warner (D-Va.), chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, revealed the consequences of that ruling: eight months of complete silence between the federal government and social media companies about misinformation. “This should terrify us all,” Warner said. The Supreme Court is scheduled to rule on the case of Mursi v. Missouri next month, but there are at least preliminary signs that the justices are skeptical of lower court decisions.

Whatever the court's decision, most of the social media executives I spoke to are intoxicated with their own sense of righteousness. Only this time they were caught doing the right thing! It's not their fault the court intervened! They remind me of my teenage years when the neighbor's son got in trouble. And they conveniently forget. Misinformation is not just the existence of lies, it's the erosion of reliable facts. And Meta, Google, X and others have been at the forefront of the attack to undermine journalism. First they killed the business model of journalism, then under the ruthless banner of “content”, they equated news with makeup tutorials and ASMR videos, and finally removed it from the feed altogether. Maybe half Spiderman is lenient.

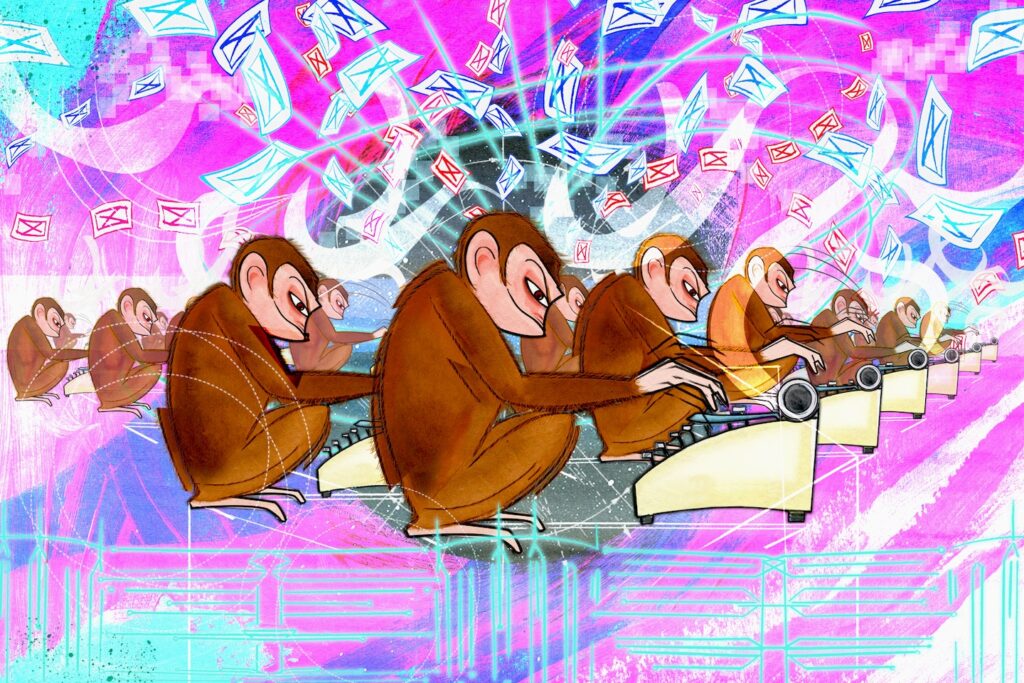

We don't know what November will be like. The obvious answer is that it won't be great. It's unlikely to be a single, imaginative, “War of the Worlds”-style deception, such as a presidential candidate being put in a compromising position or a terrorist attack being threatened, and it will at least have the advantage of being more visible and easier to expose. What I fear more is a million AI monkeys wreaking low-level havoc with a million AI typewriters, especially in local elections. Rural counties are plagued with bare bones staffing and are often in the middle of news deserts. They're the perfect breeding dish for information viruses that might go unnoticed. Some states are training election officials and poll workers to spot deep fakes, but there's no chance that all of the country's 100,000+ polling places will be prepared, especially when technology advances so quickly that we're not sure what to prepare for.

The best way to clean up a mess is to not create it in the first place. This is the virtue of a responsible adult, and of a democracy that, until recently, functioned. Maybe the Supreme Court will overturn Mursi. Maybe AI companies will voluntarily commit to increased surveillance and delay the release of new AI until 2025. Maybe an FBI Wray will sway Congress. But if none of these possibilities come to fruition, let’s get ready for Election Day in La Pierre-Land. Say a prayer, everyone.