Every year at the beginning of June, I remember my father. Eighty years ago, on June 6, 1944, he was one of approximately 150,000 Allied soldiers who took part in one of the most crucial events of World War II in Europe: the Normandy landings.

My dad graduated from high school in January 1944 at age 17; the country was accelerating high school graduation due to a manpower shortage. By the time he turned 18 in February, he was already a commissioned officer in the U.S. Navy and serving on amphibious missions. On June 6, his assignment was to man a .50 caliber machine gun on a small landing craft in the first wave of the amphibious task force that was to land the 29th Infantry Division on Omaha Beach.

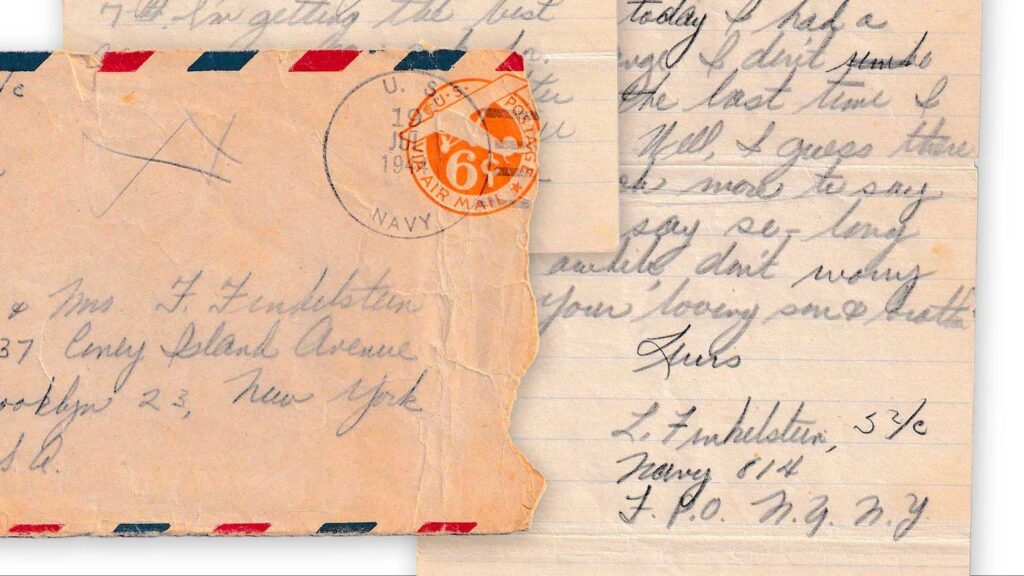

Near the shore, his landing craft was destroyed and sank somewhere near the Easy Red Sector. Before he was injured, he witnessed the death of a close friend, an event that would haunt him throughout his life and which I only learned about when he was in his late 80s and began receiving VA counseling. He was pulled unconscious from the water with oil burns on his head and shrapnel wounds to his ankles on the surface. He woke up in a hospital in England and wrote the following letter to his parents:

I share this message for several reasons: to mark the anniversary of the Normandy landings, to remember the nearly 3,000 Americans killed that day and their families who received a government telegram instead of this letter, because Father's Day is approaching, and because I am genuinely amazed at how ordinary the extraordinary was made to sound by my father and thousands like him.

July 19, 1944

Dear Mom, Dad and Rita,

Well, by the time you get this letter, you will have received a telegram saying that I was injured. I am OK and feeling better. I hurt my left leg, so I don't know how long I will be here. So, don't worry. Everything is OK. I was injured on the 6th of June and arrived at the hospital on the evening of the 7th. I am receiving the best treatment anyone could wish for. I don't know what will happen after this. It will probably be a couple of months before I can walk around again. What worries me is that you won't be receiving any mail for a while.

How is it back home? Does your dad still work during the day? I guess he'll never get used to it. Oh, I can't think of anything to write about. Have you heard anything new from Walter? Reading the Pacific news, he must be right in the thick of it. The food here is good. I had half a fresh orange today. I can't remember the last time I had one.

Well, there's not much more to say so I'll wrap it up for now, but don't worry.

Your loving son and brother, Lewis

He recovered from his wounds and was sent back to the front lines as Allied forces towed landing craft across rivers across Europe. He was part of the U.S. Navy force that occupied the German naval base in Bremen and served for over a year there — all before he turned 20. He went on to be a husband, a father, a mailman and a scoutmaster.

As he wrote 80 years ago, “Well, I don't think there's much more to say,” except these memorable words: “We remember with reverence the anniversary of D-Day. And to you, Dad, Happy Father's Day.”

David M. Finkelstein, Burke

The anniversary of D-Day has a special meaning to my family, without it we wouldn't exist.

My mother lived in the village of Sainte-Mère-Église in Normandy. She ran a café there and survived years of German occupation. Her town was the first to be liberated by the arrival of airborne forces on that eventful day, June 6, 1944. Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower would later set up his headquarters nearby. And among the soldiers who crossed the beaches of Normandy that day was an American soldier who spoke fluent French because it was his parents' native language. That man would become my father.

My father was one of the few Americans who could speak American, so he was able to have a relationship with my mother when he was stationed in her village. After the war, he returned to France and married my mother, making him a rare “war groom.” My brother was born there, and I was born after our family immigrated to the United States.

My mother's story of the morning after liberation, and the memory of seeing parachutes hanging from trees, lampposts and rooftops of young people who did not survive, always brought her to tears. My father could not put into words his feelings about losing his friends in that war. I want to remember them on this day, and all of the Greatest Generation who survived the most horrific war of our time. Their sacrifices allowed so many of us to live in a world where democracy, rational thinking and the belief that doing the right thing will prevail. Thank you!

On D-Day, my father was a member of the 506th Airborne Infantry Regiment, part of the 101st Airborne Division's Screaming Eagles, the unit that enabled the infantry division to land on the beaches of Omaha and Utah. He saw hell and survived until the Battle of the Bulge as part of a group of soldiers who became known as the “Battered Bastards of Bastogne.” During that battle, he was blown apart by a bomb, losing his left arm and his left leg. But worse than that, he lost his best friend in the same explosion. On this anniversary, I will remember my father and all the others who gave up their lives, body parts, friends, and the ability to be normal again.

Kevin Devitt, Westport, Ireland

The men who lost their lives storming the beaches of Normandy did so not only for their country but for other democracies as well. They fought at a time when the highest earners paid 94 percent income tax. They also voted without showing photo ID and still somehow believed in the validity of their elections. They were heroes then. Today, we rightly celebrate these men as heroes, but many modern Americans would consider the men who sacrificed themselves for such a political system fools.

Many who today question the value and legitimacy of our government might have found common cause then with those who denounced our elections as fraudulent, claimed our culture was being corrupted by foreigners, and spread fascist propaganda that proclaimed our policies should always be “America First.” They would have mocked President Franklin D. Roosevelt's wheelchair-bound frailty and undermined his decision-making during his final illness, despite his opposition to tyrants and appeasement. They would have denounced his administration's “socialist” New Deal policies. They would have kept the lights on during government-mandated blackouts and prioritized individual liberty. And when air raid countermeasures and other government initiatives proved unjust, they would have rejoiced in their deviations, seeing them as somehow patriotic, despite the danger they posed to others.

Those who despise our government today would have despised our government under Roosevelt, they would have undermined it at every turn, and they would never have stormed the beaches of Normandy with the other “idiots” on June 6th.

While we take pride in the memory of our grandfathers, the political context in which they made their sacrifices is important to fully appreciate the values for which they fought and the collective contributions Americans made to their success.

Keith St. Clair, Grand Rapids, Michigan

Regarding the May 29 online article “Top Republicans call for 'generational' increase in defense spending to counter America's foes”:

As a military wife, I am alarmed by Sen. Roger Wicker's (R-Miss.) calls for aggressive defense spending targeted at China.

We military families live every day in fear of what our loved ones will encounter next. Shortly before I met my wife, she was deployed as part of the Global War on Terror. I have heard countless horror stories from spouses and widows who endured wartime deployments at permanent expense. If the United States were to become embroiled in a new, protracted conflict, especially with a peer competitor, it would devastate families like mine and further damage those still recovering from previous conflicts.

Wicker's proposal threatens to do just that. His argument that “preparing for war will prevent it” completely negates the escalating arms race that his proposal would provoke. And his destabilizing nuclear weapons proposals would exponentially exacerbate the communication gap between the two militaries.

Military families want our leaders to understand that “getting tough on national security” doesn't mean adding fuel to the fire for our adversaries, but rather means investing in the people who keep our military strong and the non-military ways of running our country that avoid unnecessary wars and harm to our loved ones.

As Wicker's colleagues on the Senate Armed Services Committee consider these proposals as they debate the National Defense Authorization Act, I hope they will think of military families like mine and exercise restraint.