Open this photo in gallery:

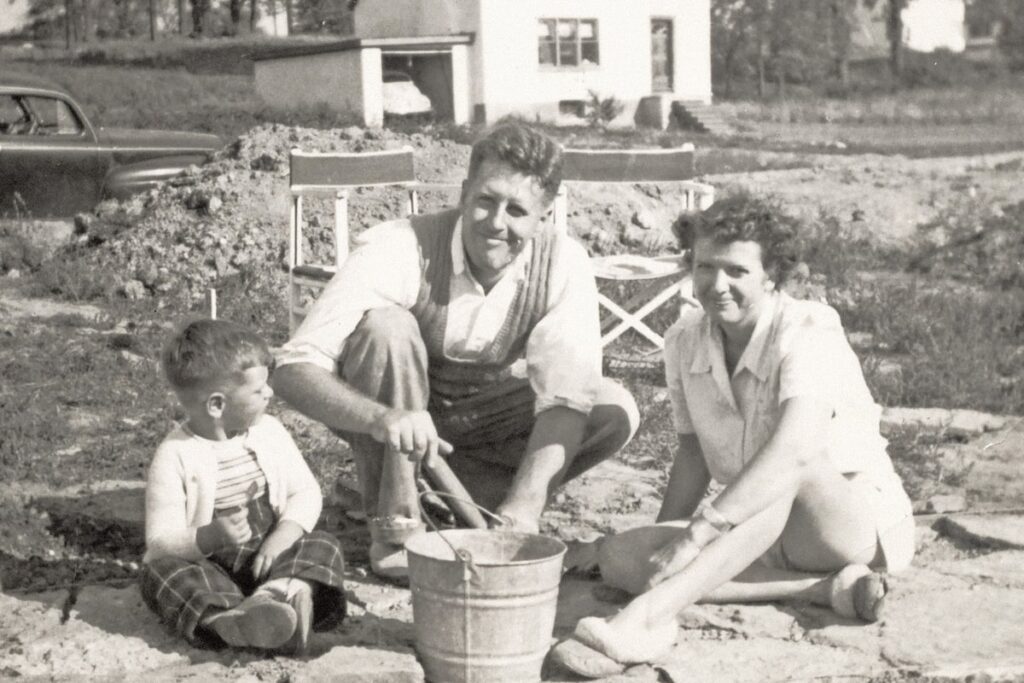

The author (right), decked out head to toe in red, white and blue Canadiens hats, with his father, Russ, and neighbour Jimmy at the community skating rink in 1958. Courtesy of Nancy Drancet

Nancy Drancet is a Kingston-based author.

Among a box of Kodak slides from the 1950s, I found a photo of myself at age 6, posing proudly on the edge of our local outdoor ice rink alongside my dad and my friend Jimmy, who lived two streets over. The guys are in winter parkas and pants, but I'm decked out from hat to toe in the red, white and blue of Les Canadiens, holding a puck on a sawed-off stick like my hero, pocket rocket Henri Richard. Jimmy and I both have beaming smiles.

Those were the glory days, not just for Hubbs but for all of us kids lucky enough to have grown up in Kingston's Grenville Park in the 1950s, 60s and 70s. It was a magical time, skating, sledding and climbing trees in a seemingly infinite yet safe world. Like Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, we were “young and carefree… and happy as the grass was green…” and Grenville Park was our knoll of ferns.

That's why more than 70 of us adult “kids” (now in our 50s, 60s and 70s) recently returned to the park from Canada, the US and the UK for a two-day reunion. Together we explored old trails, re-living childhood adventures that had remained vivid in our memories for decades. On the second day, we joined current residents in celebrating a unique 78-year experiment in Canadian communal housing that is still thriving.

It all began in October 1944, when four Kingston families gathered at the home of Ruth and Stanley Rush to discuss solutions to their housing problem. The Rushes had been inspired by the vision of urban planner Ebenezer Howard, and they had toured British “garden cities” based on his unconventional principles for quality housing, which included communal land ownership, well-designed homes with ample open space and parks, high levels of community participation, green infrastructure to enhance the natural environment, and abundant cultural and recreational facilities.

Open this photo in gallery:

Essie and Max Epplet, owners of the first home built in the park, survey the excavation site in 1946. Courtesy of Nancy Drancey

From a meeting of friends in 1944, the Grenville Society was born, and its founding members – a university professor, a high school teacher, and an industrial physicist – quickly recruited others. Within a year, the group scraped together $12,000 and purchased a 66-acre farm two kilometers west of the city in what was then called Kingston Township. An article in the Kingston Whig-Standard of October 19, 1945 announced that “Grenville Park is a new approach to Kingston's housing problem,” noting that other “garden city” communities existed in the United Kingdom and the United States.

Incorporated in 1946 as the Grenville Park Cooperative Housing Association (GPCHA), the budding organization had a lot of work to do. Turning farmland into a functioning subdivision with roads, drainage systems, sewers and running water was a daunting task, made even more difficult by a postwar shortage of labor and materials. Luckily, two of the park's founders were civil engineers, and others volunteered their expertise and muscle to get the job done. “The owners worked together to dig trenches to install the sewers,” reported another Whig-Standard article. “Thus saving at least a third of the cost of installation, savings that were passed directly on to the owners.”

As curious city dwellers drove out to inspect the new housing developments, there were occasional rumors of Communism, perhaps fuelled by sensational but false claims that one of our Grenville Park dads (the kind man who later taught me how to ride a bike) was part of a Soviet spy ring. Perhaps the fact that our neighbours bought groceries in bulk also contributed to this misunderstanding, especially since red flags would fly from the organisers' clotheslines as the weekly deliveries arrived.

Yet despite the communal ownership and management of the commons, the large lots and distinctive, original designs of the newly built homes would have conveyed the exact opposite message: Strongly individualistic in many ways, the people of Grenville Parker were united by a common desire to create a community that reflected the “Garden City” ideal.

Open this photo in gallery:

Residents like Gord and Ida Fraser (pictured here with their son John) worked together to build their homes in Kingston's Grenville Park community housing complex. Courtesy of Nancy Drancet

Two World War II veterans who enthusiastically joined the venture were my father, Russ Kennedy, and our next-door neighbor, Elmer Axford. “After seeing so much destruction and chaos in Europe, I think our fathers tried to create a community as far removed from it as possible,” Elmer’s son, Dave, told me. “Instead of waiting for commercial developers, they took the initiative and built their own neighborhood together.”

Open this photo in gallery:

1944 Tentative plan for Grenville Park by the Grenville Association.

His father, a civil engineer, was on the volunteer team that designed the park's roads, water supply and gravity sewer system. (At a time when Kingston still discharged all its raw sewage directly into Lake Ontario, Grenville Park had its own sewage treatment plant.) A 1947 report to the Grenville Park Commission noted that “snow removal was accomplished by horse-drawn snowplows.”

After the park became part of Kingston in 1952, the city took over responsibility for roads and public services. But oversight of the association's “common lands” remained the responsibility of the cooperative community. And it is these common lands (set aside for “parks, playgrounds and other community purposes”) that made our childhoods in Grenville Park so memorable. The number of children under the age of 12 in the park peaked in the early '60s, totaling 132.

“We were free to roam the 66 acres and have mostly innocent adventures. There were plenty of common areas, including an ice rink, baseball fields and tennis courts maintained by our fathers. We shared events like potlucks, fireworks and square dancing. We knew all 55 families,” says Sue Chamberlain, one of the reunion organizers, adding, “It really felt like we were raised by a village.”

When my mother, Shirley, was stricken with debilitating cancer in 1959, our family experienced firsthand the power of a village. The community rallied together to support us, and for years afterward, the park mothers rallied around me and my siblings without my father ever needing to ask for help. At the time, we kids never questioned that support; it wasn't until later that we realized just how special that bond was, and it still is, according to current GPCHA president Steve Gammon.

“With 12 acres of parkland, woodland and recreational facilities, Glenville Park is a special place to live,” he says. “For many current residents, it's our shared commitment to stewardship of the land that builds community among neighbors. We hope that the original residents will view what we do with the land today favorably. Glenville Park was unique in 1946 and will remain unique in 2024.”

Curious to see how the model community envisioned by the park's founders compares to the current state of apartment housing in Canada, I consulted with David Gordon, professor and former dean of Queen's University's Department of Urban and Regional Planning (which Grenville founder Stan Rush helped establish in 1974). Gordon began by pointing out that, because Grenville Park is intended entirely for residential use, it is technically a “garden suburb,” similar to England's Hampstead Garden Suburb, a historic planned area near Hampstead Heath in London.

Gordon sees similarities between “GPCHA’s friendly social organization” and “the shared ownership of common spaces that characterize today’s suburban townhouse condominium projects.” But Grenville Park’s large lot sizes and low density are unlikely to be replicated in today’s more compact suburban planning, he suggests.

Which is all the more reason for us old folks who experienced the Grenville Park phenomenon to revisit our old haunts and homes and relive those memories while we still can.

Open this photo in gallery:

Glenville Park Hula Hoop Party, 1958. Courtesy: Nancy Drancet