Her mother doesn’t understand her change in hairstyle. She wants to be there for her daughter, but she’s deeply afraid of saying or doing the wrong thing. They’re both navigating the grief that comes with losing a father and a husband, but what San Diego author Anastasia Zadeik wanted to make clear in her second novel, “The Other Side of Nothing,” is that her characters love each other with a tremendous depth and strength.

A report last fall from the Harvard Graduate School of Education (“On Edge: Understanding and Preventing Young Adults’ Mental Health Challenges”) notes that 36 percent of adults 18 to 25 in their survey reported anxiety and 29 percent reported depression — rates double that of teens. Zadeik’s story follows characters who are dealing with diagnoses for depression and bipolar disorder, and the ways that their families and friends choose to join them in their journey.

“I write from a place of lived experience and research, and education that I’ve done for myself on that lived experience. None of us have exactly the same experience, but I’m trying to tap into as much information as I can so I can write from a place that I feel confident because of the information,” says Zadeik. “For this book, I spoke extensively with a psychiatric nurse that worked in one of these private facilities, just to try to make sure that I’m being realistic. That’s really important for me.”

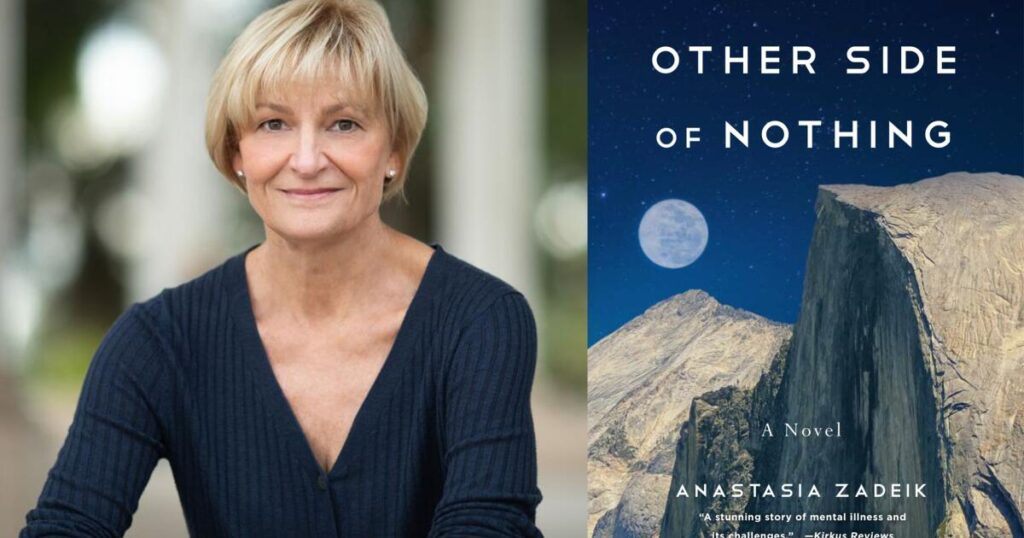

A writer and editor with a degree in psychology and a previous career in neuropsychological research, she was inspired by her own mental health challenges, and that of close family members, to write this story. Her debut novel, “Blurred Fates,” won the 2023 Sarton Award and the National Indie Excellence Award in contemporary fiction. Currently serving as communications director for the San Diego Writers Festival, a mentor for So Say We All, and a board member for the International Memoir Writers Association, she took some time to talk about destigmatizing mental illness and tapping into empathy and a change in perspective, particularly when interacting with young people and their mental health. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Note: This story mentions suicide and self-harm.)

Q: “The Other Side of Nothing” is about two young adults who meet at a mental health facility, bond over common interests in art and philosophy and fall in love, and navigate their own (and each other’s) mental health challenges and how those issues also affect their relationships with their families. In your author’s note at the end of the book, you talk about personal experiences similar to that of your characters. Are you comfortable sharing a bit about those personal experiences?

A: One of my main goals in writing this book is to open up conversation about these topics, so that other people feel comfortable to talk about it, if they want to. No one is required to share details about their physical or mental health, but if you want to and if you’re looking for support, I’m hoping that this book, in book clubs and just in people reading and talking about it with their family and friends, that they understand they’re not alone if they have these things going on in their own lives, and that they feel comfortable talking about it.

I realized, only probably in the last 10 years, that despite my training in psychology and working in neuro-psych research, I didn’t turn it on myself, and I had all of the symptoms of someone who’s depressed and anxious, most of my life. I have struggled with insomnia since I was in middle school. I had something called “nervous colitis” when I was 9 or 10. There were all sorts of things that were pointing to it, but back in that time, it wasn’t really discussed much at all. So, I learned about some treatments on my own, strategies to cope. For me, that was primarily exercise, journaling, yoga, and those things carried me along well enough, until about three years ago. It wasn’t so much that I didn’t want to live, I couldn’t live the way that I was living and I didn’t see any way out. That’s an important thing, I think. For a lot of people, it isn’t really that they want to die; it’s that they can’t [continue] to live the way they are. They can’t stand the pain anymore. It actually becomes a physical pain to live with.

I stormed out of the house, yelling back to my husband, “Maybe you’ll be lucky and I’ll jump!” I was going on a hike and he knew where I was going, I was going to Torrey Pines, which has all these areas where there are cliffs above the beach. I hike there once or twice a week. Looking back on it, I was not thinking clearly, I just reached this breaking point and I couldn’t pull myself back. It was during COVID, I forgot my phone, and I borrowed a phone from someone to text my husband because I was concerned he was going to call my kids, and I didn’t want my kids to be worried. That was the first glimmer in my mind that I was thinking about my kids. I wrote a text message to my husband, “It’s me, I’m OK.” As soon as I typed the words, I knew I was lying. I wasn’t OK and I realized that that’s something I’ve been saying my whole life, ‘I’m OK. I’m fine,’ when I’m not. Finally, as I was walking, I was thinking about the logistics of it — how long will it take me to hit? Should I jump? — I started thinking bigger than that and thinking about how hard it was for me when my parents died and how I was going to be doing that to my kids. It was enough to keep me from doing anything, and I sort of hugged the side of the path and headed back up toward the parking lot where I ran into my best friend, who my husband had called. The first thing I said to her was, “I’m OK,” and she said, “You’re not OK and that’s OK. It’s OK that you’re not OK. We’re here, we’ve got you.” That afternoon, I made what I call the most difficult call of my life — telling someone I didn’t know that I wanted to end my life. Looking back on it, it was also one of the best calls I’ve ever made because as soon as I said those words, and as soon as the message came back to me that ‘We’re going to do this, and then we’re going to do this,’ I realized I was letting go. I felt this lightness that I was letting go of a burden that I’ve been carrying around for decades. I think that’s something that a lot of people do, we hold on to the things that we think define us and I didn’t want my depression and anxiety to define me anymore.

I also have a daughter who struggles with depression. I don’t like to talk too much about her story because it’s her story, but I can say that I’ve been on the side of the mothers in this story, of being in a position where you can’t make decisions for your kids. They’re young adults, they have to make those decisions for themselves. It feels powerless and it’s heartbreaking to not be able to save your kid, to watch them make decisions when you’ve been in that position of knowing what it’s like when you hit that place where you can’t make the decision anymore for yourself, to see your child in it and then not be able to say, ‘Wait a minute, we’ve got to do something here.’ In the book, I try to address both the experience of being someone who’s in that space themselves, and then also the mothers.

And I have a nephew who was really the inspiration when I first started writing this book. After my nephew attempted to take his own life, my sister and I spoke at length about the experience of being a mother in that situation, and she shared so many details about what she went through. It’s so much that I think, for parents in this situation, you’re new to this world and you’re just being flooded with names and things you don’t understand and that don’t exist in your vocabulary. The people in that world are talking in that language because that’s their language, but for someone new to it, it’s just overwhelming. One of the things that she said to me early on was that not only were these individual experiences—watching your kid get put into a coma, being asked to leave the room when they take them out of the coma because you might be the reason—but all of these experiences are made worse by the fact that people didn’t know what to say. They were silent. Even her closest friends didn’t really know what to say. She’s super involved in our community. She’s the one who always brings the casserole when things are going bad for a family. Mental illness is not a casserole dish disease; people don’t do that. That’s also because people don’t know what to say, so they say nothing, and it makes you feel even more alone. Now, it’s just exacerbated by the fact that people don’t know what to say.

Q: I’d imagine that this was a story that you approached quite carefully and sensitively. What were some of your concerns early on with writing this book, and how did you deal with those concerns?

A: One of my concerns, obviously, is that I don’t want people to think that I’m advocating for a particular treatment modality. I’m not. I’m not saying that medicine is for everybody, I’m not saying that everybody experiences the same thing. These are four fictional people. I am not representing, nor am I trying to represent, the entire scope of the mental health and mental illness world. It worries me that people would think I was saying, ‘You should take medicine’ and I’m not. I’m also not saying that you shouldn’t take medicine. I’m not saying that people with bipolar disorder, that their creativity depends upon their mania. I’m not saying that. There are a lot of researchers that are looking at that very question, even today. Looking at the rates of hospitalization in people who are deemed creative and comparing that to the rate of hospitalization of people who are not, so there’s still a lot of unknowns in that space. I do not want people to think that I am trying to address all of those, nor that I have the answers; I don’t have the answers to a lot of these questions, but I’m starting to see that the questions are important for us to be talking about. So, that’s my biggest fear, was that people would think that.

I was also afraid that young people who were depressed, or who might have a diagnosis or might be undiagnosed, would use this as some kind of example of how to behave. I don’t want people to think that, either. Again, this is just a representation of four people struggling. There’s been some discussion with various people involved in the publication of this book about whether or not to categorize it as a crossover with YA [young adult] because the characters fall into that category. They were worried that it could be ready by young adults and be seen as some kind of guide, and that’s something that you don’t want. A statement that I’ve heard a number of times and totally agree with is that when you are writing the book, the book is yours, but as soon as you put it out into the world, it’s the reader’s book and you can’t control what they’re bringing to it. We all bring our intergenerational influences and all of the things that make us who we are—our experiences, our current context—all of that becomes a part of the process of reading your book.

Q: I appreciated seeing Julia’s mother, Laura, grapple with unlearning the harmful ways she’d been raised to suppress and deny her own emotions, her real-time realizations that they weren’t helpful while also slipping into the habit of enacting the stoicism, the denial. Why was it important to you, and to the story, to demonstrate this tension and struggle?

A: What I wanted to try to show is some of my in-laws and some of my friends were raised with that mentality of “crying doesn’t do you any good, no one wants to see you cry. If you’re going to cry, go to your room. Pull yourself up. I got through all of these things when I was a teenager, you’re being overdramatic. She’s just a teenager being overdramatic. He’s just lazy.” I’ve heard these things about kids who are struggling with mental health issues, from their parents, who are smart, reasonable people. In one case, one of the people that I spoke with is a doctor who was saying things like, “I went through much worse when I was growing up.” There’s this attitude that it’s either laziness or procrastination, or they’re just moody. Yeah, those can all be true of teenagers, and of any of us. We can have bad days, we can have moments where we are not functioning at 100 percent, but that is not what is often happening. I wanted to show how that is somewhat cultural, it’s intergenerational. We can’t control the way we were raised, but what we can control is when we learn that that’s not a healthy coping mechanism for dealing with your kids, hopefully, you can look at it somewhat objectively and say, ‘Maybe I need to understand this from a different perspective.’

Q: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention highlights trends about the mental health of American youth, including information about it worsening even before the COVID-19 pandemic, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation. Among the recommended responses to better support the mental health of young people is the importance of strong relationships and connections with the older adults in their lives. Can you talk about how we see this illustrated in the relationships that Julia and Sam have with the most prominent adults in each of their lives? What was your approach to their relationships with their parents and the paths that those relationships took? And what role did those relationships have along the journey each of the younger characters were taking in their mental health?

A: One thing I have to say off the bat is that all of these characters love the people in their families. Julia loves her mother and her mother loves her, but they just aren’t communicating. This is not a contentious relationship. They may not be “getting along” in the beginning [of the story], but it’s not for lack of concern or lack of love. Julia wants her mom to understand her. She leaves that packet of information for her in her bedroom with a Post-It note “For Mom” on it, in the hopes that her mom will come in and find it and begin to understand what she’s going through. Even in the beginning, when Laura doesn’t know what to do and she follows the advice of one of the support groups to give her daughter time and space, there’s a recognition that she’s doing that because she’s grieving herself and she doesn’t really know what to do. She kind of uses that as an excuse not do anything, but not because she doesn’t love her daughter. She wants her to be well, she just has no idea how to help her.

I think one of the things I wanted to convey in the book, one of the messages I hope people take away, is that education is super important in families and in parents to learn as much as you can about the signs of suicidality, to learn as much as you can about how to support your child when they’re depressed or anxious. About informing yourself about the societal impact of social media and all of these things on young people, to kind of get into their world. I think it really is a challenge for parents right now because their kids are growing up in a very different world. It’s a world where you have to have an acronym for “in real life.” I mean, when I was growing up, everything was in real life.

[The characters] are just human, so they’re fundamentally flawed. I remember when I was writing my first book, I was talking to a psychiatrist and a psychologist about family behaviors that are most helpful to raising well-balanced children. Both of them immediately said, “Dinnertime.” I think that, in this day and age, it’s tough to find time where your kids are not connected to a device, where you can be there and have a conversation. I think that those are incredibly important. It gives the kids a ballast in the storm of life. I think those relationships, being able to connect with older folks who have wisdom and who have experiences that they can reflect upon, is really important for kids.

Q: In one of the chapters from Laura’s perspective, as she’s on this path to heal and build her relationship with her daughter, she talks about how the people around her respond to her family experiencing the loss their husband/father from cancer by avoiding them or saying things that aren’t particularly thoughtful or sensitive. And, she admits that as much as she is trying with Julia and wants to do whatever is right and whatever will work, “she had no idea how to do it.” Why do you think so many of us still have such a hard time with this? With supporting people we know who are experiencing loss, who are experiencing mental illness/mental health issues?

A: I was just reading The New York Times and they had a whole article on how artists process grief for creativity and how it helps to heal. Some of them were writers, some of them were visual artists. I think, as a society, we don’t deal well with conversations about death, first of all. We don’t like to talk about approaching the end of our lives. We don’t know how to have conversations. Even when it’s clear that someone is dying, we still find it awkward to talk about that with them. When my father was dying, about nine years ago, he was a minister and he counseled people. He used to park in the space for clergy at the hospital and go in and visit people who were dying, but talking about his own death was so hard for him.

I think it’s the ultimate lack of knowing what’s going to happen next. Throughout history, we’ve struggled to control death. The ancient Egyptians filled these tombs with all of the things they thought they would need in the afterlife. Humans have always had a concern for the unknown, which is anything outside of our current life. I think that facing that unknown, for ourselves and for others, is daunting. Then, once you’ve lost someone, grief is such a personal experience and everyone does it so differently. I think there is that concern about saying the wrong thing. When I’m on social media and I’m looking at people who’ve posted about a loss, people say, “My sincere condolences, so sorry for your loss.” I’m not saying that those aren’t useful or that we don’t feel supported, we just don’t feel comfortable going deeper, usually.

I think mental illness is another thing we can’t control. It’s another unknown for a lot of people. When someone dies by suicide, you very rarely read about that in an obituary. Very rarely is the cause of death mentioned when it’s a death by suicide. It’s taboo, it’s still something we don’t say, and I think one of the reasons for that…is we are comfortable with people who are struggling to live. When someone has cancer or someone has an illness, we can rally around the family and that person because they’re struggling to live. We understand struggling to live, but somebody who actually wants to die? That is a strange concept for us to accept.

Q: There’s been a much more noticeable and considerable effort over the past couple of decades to destigmatize mental illness and mental health needs. How do you see “The Other Side of Nothing” fitting in with this work to expand people’s perspectives and understanding?

A: I agree, we have come such a long way from 20 years ago and I think that we’re moving in the right direction. There are so many people you can follow on social media that put out daily, positive messages, who are talking openly about depression and anxiety and bipolar disorder. All of the organizations that I mentioned [in the author’s note in the book, which include the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988lifeline.org, or the National Alliance on Mental Illness’s helpline at 800-950-NAMI (6264) or nami.org/help] have websites and they put out information to people online, and that’s fantastic.

There are two quotes that I kind of combine when I think about this issue and why I wrote this book: one is from last fall when the surgeon general said that mental health has become the defining public health and societal challenge of our time, and Neil Gaiman said that fiction builds empathy. So, my goal in writing this book was for it to build empathy for those who are struggling, and for their families. And, I know it sounds trite, but maybe people will deliver a casserole. Maybe somebody will rethink their way of dealing with someone who’s going through this and maybe when they hear that one of their friend’s kids is struggling, they’ll call up just to say, “I’m here for you” because we sometimes don’t do that.

I also hope it inspires people. One of the best ways to combat any kind of stigma in our world is through education, and I hope that people take the opportunity to learn more about ways that you can support people who are going through this and take the initiative to look at some of the resources that are out there. Look at some of the ways that you can learn more about what it’s like to be suffering from one of these mental illnesses, what it’s like to be a family member, how to look for it in your community, how to be supportive. Getting rid of the myth that it’s a bad idea to ask somebody if they’re thinking about killing themselves. It’s not going to put the idea in their head. If you’re feeling suicidal, you’ve thought of it and you might be thinking, ‘I can’t ever say anything about this. This makes me weird, this makes me unacceptable.’ But, if somebody asks you if you’re thinking about hurting yourself, it gives you that opening, it lets you talk about it. It lets you open up to someone who can help you get rid of the burden. The book itself is not an answer, but it will hopefully raise awareness and awareness leads to action.