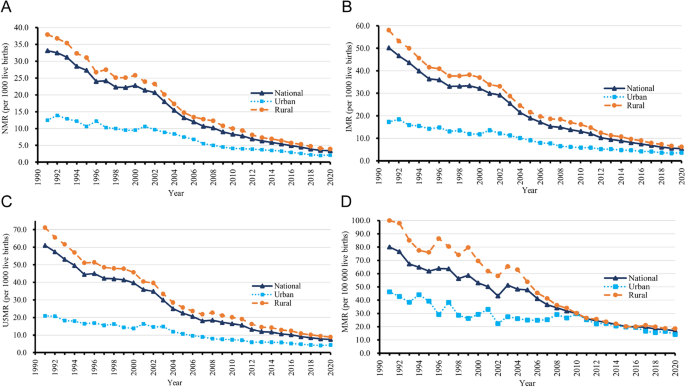

In this study, we used a joint-point regression model to analyze the trends of China's MCH indicators and urban-rural disparities from 1991 to 2020. We found that the NMR, IMR, U5MR, and MMR showed an overall declining trend at the national level, and an individual declining trend in urban and rural areas. The urban-rural disparities have narrowed significantly over the past three decades.

China's remarkable achievements in maternal and child health can be attributed to the rapid socio-economic development since the Reform and Opening Up, the significant improvement of maternal and child health care services, and effective government policies focused on maternal and child health.1,26 Therefore, the following discussion focuses on exploring the potential relationships between China's maternal and child health policy implementation and trends in maternal and child health indicators, as well as trends in urban-rural disparities.

The inflection points of the three infant mortality rates were similar. Urban IMR and U5MR declined rapidly from 2003 to 2008, and NMR declined from 2004 to 2007. After the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003, the government increased spending on MCH and improved the National Maternal and Child Mortality Surveillance System. 27 In 2004, the Chinese government launched the “Neonatal Asphyxiation Resuscitation Training Program” to reduce neonatal asphyxiation deaths. 28,29 These changes may have helped to improve the quality of MCH services and reduce NMR, IMR, and U5MR.

The three urban infant mortality rates showed similar trends to the national indicators, suggesting that a high proportion of infant mortality occurred in rural areas across the country.30 In rural areas, the downward trends of these indicators were evident from 1991 to 1995 or 1996, which is likely related to economic development. During this period, China experienced the fastest economic growth, which promoted significant improvements in living environment, education, and medical care in rural areas as well.31,32,33 However, the downward trends of rural infant mortality rates slowed down from 1995 or 1996 to 2000 or 2002, which may be attributed to the expansion of the national U5MR surveillance system. Before 1995, China established two nationwide MCH surveillance networks, MMR and U5MR, covering 81 surveillance sites. Since 1995, a comprehensive MCH surveillance network has been established through the integration of MMR, U5MR, and birth defect surveillance, and the coverage of U5MR has been expanded to 116 surveillance sites.34 This integration has improved the quality of MCH surveillance in the region and may have reduced the three-percentage underreporting in rural areas.

The decline in the U5MR in rural areas from 2000 to 2006, and in other rural areas and the whole country from 2002 to 2005 all accelerated. Perhaps the launch of the World Bank-funded Health and Children master project and sub-projects in 1998 and 1999, which provided direct financial support for pregnancy,35 helped to reduce infant mortality in resource-limited areas. Meanwhile, in 2001, the State Council promulgated the China Child Development Plan (2001-2010) and the China Women Development Plan (2001-2010). These plans established maternal and child health guidelines and promoted extensive health education activities with a focus on reproductive health from 2001 to 2010, which had a significant impact on maternal and child health.

After 2008 or 2009, the decline in NMR, IMR, and U5MR in rural areas accelerated again, and after 2009, the ratio of IMR to U5MR declined again. The rural maternal and child hospital birth subsidy system launched by the former Ministry of Health in 2008 may have played a role37. This system improved the resource utilization efficiency of maternal and child health services, and further increased the rate of hospital birth and successful birth. The 2009 “Opinions on Deepening the Reform of the Health System”38 proposed to continue the subsidy system for rural maternal and child hospital birth and extend it to all pregnant women and newborns in rural areas39,40. In addition, the Basic Public Health Service Project was implemented to provide a complete health service cycle for newborns and primary prevention measures such as folic acid supplementation for mothers41, which further reduced the three indicators in rural areas. However, problems such as economic stagnation42, regional disparities in maternal and child health services43, irregularities in maternal and child health staff44, and a general lack of resources for maternal and child health45 remain in rural areas. These considerations highlight the need to continue and strengthen efforts to promote maternal and child health.

In rural areas, the MMR declined rapidly from 2004 to 2012. This could be attributed to increased funding for MCH by the central government after the 2003 SARS outbreak and the implementation of a new rural cooperative health system. The above measures reduced out-of-pocket expenses for hospital births and promoted the utilization of obstetric health care resources27,29, which have a positive impact on reducing the MMR. However, since 2012, the decline in the MMR in rural areas has slowed. This trend may be related to the shift in the causes of more frequent maternal deaths to factors that are difficult to detect and avoid, such as cardiovascular diseases and other non-communicable diseases12,46. Studies have found that low education levels and health literacy, as well as limited MCH resources, may also be responsible for the rise in the MMR in rural areas47,48. These deep-rooted factors make it difficult to further reduce the MMR.

Our analysis highlights the inequality between urban and rural areas in China. Over the past three decades, the four maternal and child health indicators have consistently been higher in rural areas than in urban areas. This may be because rural areas are more likely to suffer from economic and educational underdevelopment, poor transportation, and a shortage of medical personnel and infrastructure than urban areas. 2 However, the decline in the four indicators was greater in rural areas than in urban areas throughout the study period, and the urban-rural maternal and child health disparity has narrowed. This narrowing likely reflects China’s rapid economic development, the improvement of general educational levels through a nine-year compulsory education system,49 and the adoption of several specific national policies on rural maternal and child health.50 Despite these advances in rural maternal and child health, large inequalities remain between urban and rural areas. Future efforts to improve child health should therefore focus on rural areas. Although the MMR was roughly comparable between urban and rural areas after 2010, the disparity between the two types of regions may have begun to widen since 2016. Therefore, efforts to improve maternal health need to continue and be intensified.

To achieve further reductions in NMR, IMR, U5MR, and MMR, the following recommendations are made at the national level. First, China should prioritize strengthening its MCH monitoring system51 to ensure robust data collection as well as regular analysis of trends in MCH indicators and their potential determinants. Second, technical training and skills assessment for personnel52 who monitor and evaluate MCH services should continue. This is essential to accurately assess MCH trends and implement effective interventions. Third, differentiated MCH policies should be developed for urban and rural areas, taking into account the specific needs and challenges of urban and rural areas.

The strengths of this study are as follows: To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use joint-point regression models to analyze trends in NMR, IMR, U5MR, and MMR at the national level and in urban and rural areas separately in China. In addition, this study is the first to explore the potential association between China's MCH policies and trends in MCH indicators, including urban-rural disparities. Moreover, this study uses the most recent available data to examine trends over a 30-year period from 1991 to 2020.

This study has several limitations. First, the primary data were obtained directly from the China Statistical Yearbook, so the findings may be affected by factors such as changes in the coverage of surveillance networks and guidelines, and underreporting rates. Second, the joinpoint regression model used in this study is primarily a trend analysis method and is not intended for causal analysis. Because this study could only provide insights into inflection points based on indirect evidence from other studies, further research was needed to explore the causal relationship between these points and various policies. In addition, because of the comprehensive analysis conducted using the joinpoint regression model, alternative methods for processing and interpreting trend changes were not explored. Future studies should focus on collecting additional data on potential influencing factors to further verify the reasons for trend changes, and more extensive data collection and analysis may be required to deepen our understanding of changes in maternal and child health indicators.