Donte’ Phillips discovered a new purpose after tragedy struck his playing career in

the 2014 season.

CREATORS

Donte’ Phillips is a natural defender.

It’s apparent in his career with the Wisconsin Department of Justice (DOJ), in his

relationship with his family, and it was evident on the field with the Texas Tech Red Raiders.

The 6-foot 2-inch defensive lineman experienced only two losses in high school and

was named conference defensive player of the year his senior year, providing him with

multiple scholarship offers. But his path to Texas Tech University was a bit of a surprise, as was most of what came next.

Milwaukee

Donte’s parents packed boxes into their blue Pontiac in 1993 and moved from Ypsilanti,

Michigan, to Milwaukee. His father had just graduated from Indiana University with

his law degree and the family was moving so he could take a job as a public defender.

The family’s car moved through southern Michigan, through Chicago, and then turned

north. The landscape of corn fields and farms slowly changed. Buildings appeared as

the skyline of Milwaukee unfolded before Donte’s eyes.

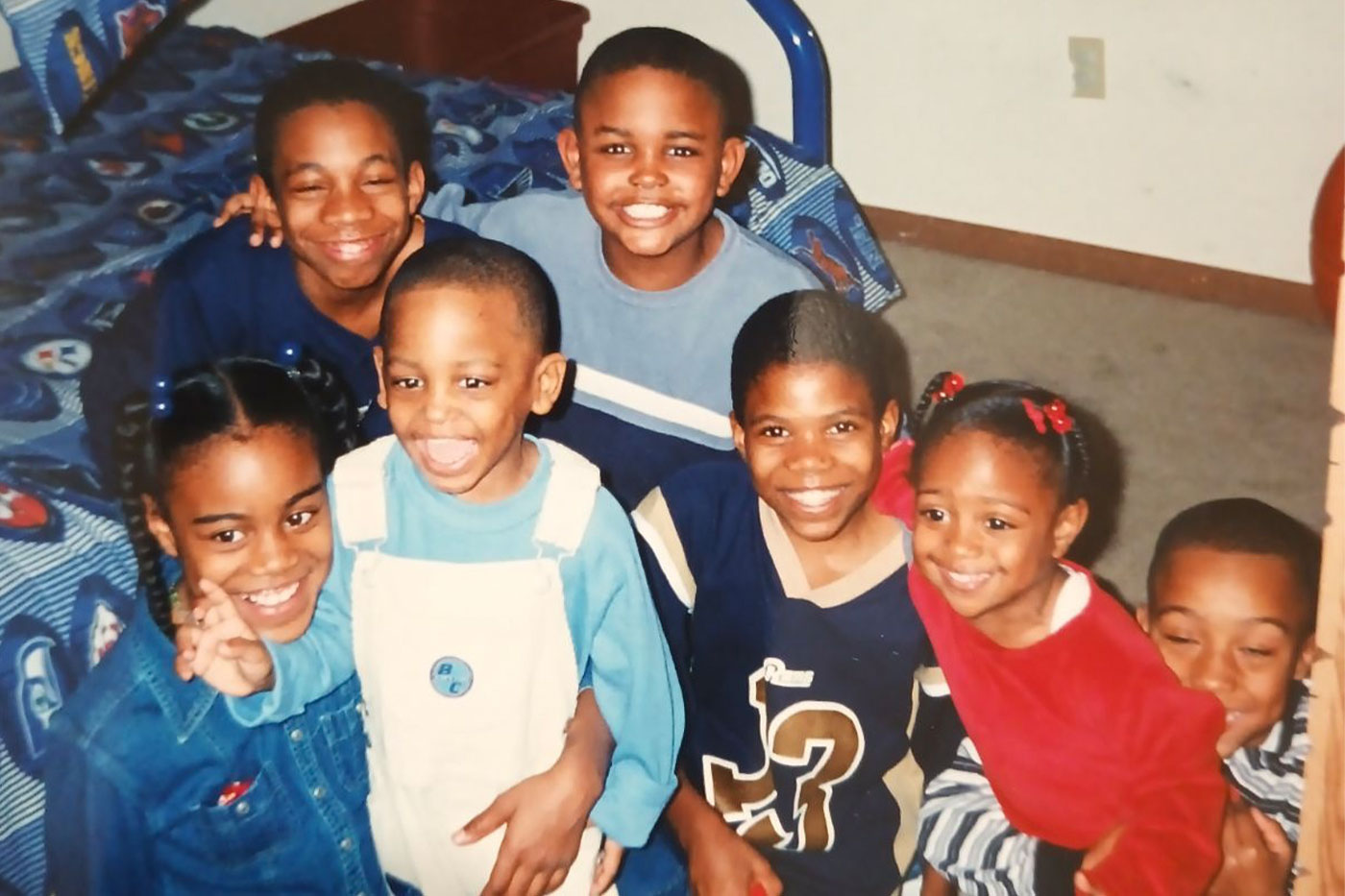

Donte’ (in back) with his cousins

Donte’ (in back) with his cousins

Donte’s family lived in the city, and he attended local public schools. However, due

to a lack of appropriate speech resources, his parents sent him to a school in the

suburbs.

“As a child, I had a severe speech disfluency,” Donte’ said. “I could speak, but few

had the patience to understand what I was trying to say.”

His parents enrolled him in a school that could provide support.

Classroom games such as “Around the World,” which required quick verbal answers to

trivia questions were a point of extreme frustration for Donte’.

“I was smart, and I usually knew the answer. I just couldn’t say it in time to win,”

he said.

Luckily, he had kind classmates who gave him a chance when they saw he had an answer.

That space to be himself, with the addition of speech therapy, got Donte’ communicating

well by fifth grade.

He still felt out of place, though.

“I was one of three Black kids in my elementary school,” he said. “I also was the

biggest kid in my class, and I had a stutter. I felt different.”

Donte’ didn’t let his differences keep him out of the game though. By fourth grade

he was playing flag football, and he was in contact football the following year.

“The football field was my comfort zone,” Donte’ said. “It was a place where I could

express myself freely and my actions spoke for me.”

It was a place that made sense to him. As Donte’ got older, his passion for football

only intensified. By middle school, he knew he wanted to play college ball. He planned

to study business and work for a large company, maybe sports related, after hopefully

retiring from the NFL.

His father wanted him to study law, but Donte’ didn’t feel that was his path. While

he greatly admired his father, Donte’ was going to make his own way, just like his

dad.

“My father grew up in the projects in Brooklyn; he is the definition of a self-made

man,” Donte’ said.

When Donte’ was still in fifth grade, his father told him he wasn’t going to pay for

his college tuition. Apparently, his father was joking, but Donte’ took the statement

at face value and thought if his dad made his own way, so would he.

With one stipulation.

Donte’s younger brother Malik was born four months prematurely. At barely over 20

weeks – it’s a space doctors often refer to as the edge of viability.

“We had no idea what would happen,” Donte’ said. “Some babies pull through, many don’t.”

From the minute Malik was born, Donte’ was at his side. He wanted to hold his brother,

help feed him and play with him. He was a natural caregiver. He would do anything

for his younger brother.

“Malik was my biggest motivator for playing college football,” Donte’ said. “I knew

if I got a scholarship, that was more money my parents could save for Malik and his

education.”

And on that afternoon, as Donte’ sat in his father’s car talking about future goals,

he made a deal with his dad.

“If I get a full-ride scholarship, you have to pay for Malik’s college,” Donte’ challenged.

“You got yourself a deal,” his father said.

College Ball

Donte’ verbally committed to play for Indiana University during his junior year of

high school. For almost two years, that plan remained intact.

“My dad was excited about me following in his footsteps,” Donte’ said. “I was excited

because I’m a family guy, and Bloomington was halfway between Ypsilanti and Milwaukee.

I wanted all my family to come watch games.”

Donte’ verbally committed under Hoosier coach Bill Lynch, who had him on the defensive

line. Donte’ went on his official visit a month before national signing day. The team

had just named a new coach and while visiting, Donte’ was told he’d be changing positions.

He’d trained for the defensive line. But the new coach made it clear: it was a new

position, or no position.

“I had to go back to the drawing board and put myself on recruitment lists again,”

Donte’ said. “I sent my tapes to universities that still had scholarships to offer.”

Even in the 11th hour, coaches wanted him.

He received multiple offers but took his four remaining visits to Western Michigan,

Ball State, Penn State and Texas Tech. Donte’ knew he had some great options, but

there was something about Texas that drew him in.

“I grew up on the television show ‘Friday Night Lights,’” he said. “I had always heard

Texas football was the best in the country. I wanted to challenge myself and compete

against the best.”

Donte’ also was aware of Texas Tech because of the famous (Graham) Harrell-to-(Michael)

Crabtree touchdown that upset No. 1-ranked Texas in 2008, landing Crabtree on the

cover of an NCAA video game Donte’ played.

The idea of playing on that field seemed magical to Donte’ but at the same time, the

idea of moving far from family was hard to stomach.

“Leaving my younger brother was one of the hardest choices I’ve had to make,” he said.

“He was the whole reason I wanted to play, so the idea of doing that across the country

was tough.”

Donte’ spent time mulling over the pros and cons of each program. On the morning of

signing day, he woke up and said he “just knew it was Texas Tech.”

Red Raider Football

Donte’ arrived at Texas Tech in 2011, recruited by former head coach Tommy Tuberville.

“The brotherhood with my teammates was one of my favorites parts of being a Red Raider,”

Donte’ recalled. “From off-season conditioning to competing against each other and

enduring the grind of the season, our bonds became tight.”

The defensive lineman recalls the incomparable feeling of walking into the Jones AT&T Stadium. He’d walk the field before each game, soaking up the atmosphere. He took a knee

at the 50-yard line while listening to “What You Live For” by Lil Bibby.

Donte’ (left) and defense walking onto the Jones

Donte’ (left) and defense walking onto the Jones

“That song had a way of reminding me that no matter what was happening at the time,

for the next few hours, I was in my happy place,” he said.

When it came to academics, Donte’ had planned to study business but when he met with

his adviser, it became clear the classes he’d need to take conflicted with his training

schedule.

That’s when he looked at the College of Media & Communication (CoMC).

“One key thing had changed since I first wanted to go into business; social media

had blown up, the way the world communicated was evolving,” Donte’ said.

Donte’ noticed Facebook and Instagram were no longer just for personal use; businesses,

brands and even sports teams were migrating to these spaces at a rapid pace. He was

fascinated by the phenomenon. He declared a major in media strategies, and it didn’t

take long to know he’d made the right choice.

“I really enjoyed the curriculum,” he said. “I learned the history of the industry

and how much it has changed in Bill Dean’s class, Foundations of Media & Communication. That class hooked me right away and

provided a spark for the rest of my studies.”

Donte’ admits it felt ironic to become a communication major as someone who’d had

a speech disfluency.

Little did he know it wouldn’t be the last setback he’d overcome.

The Game

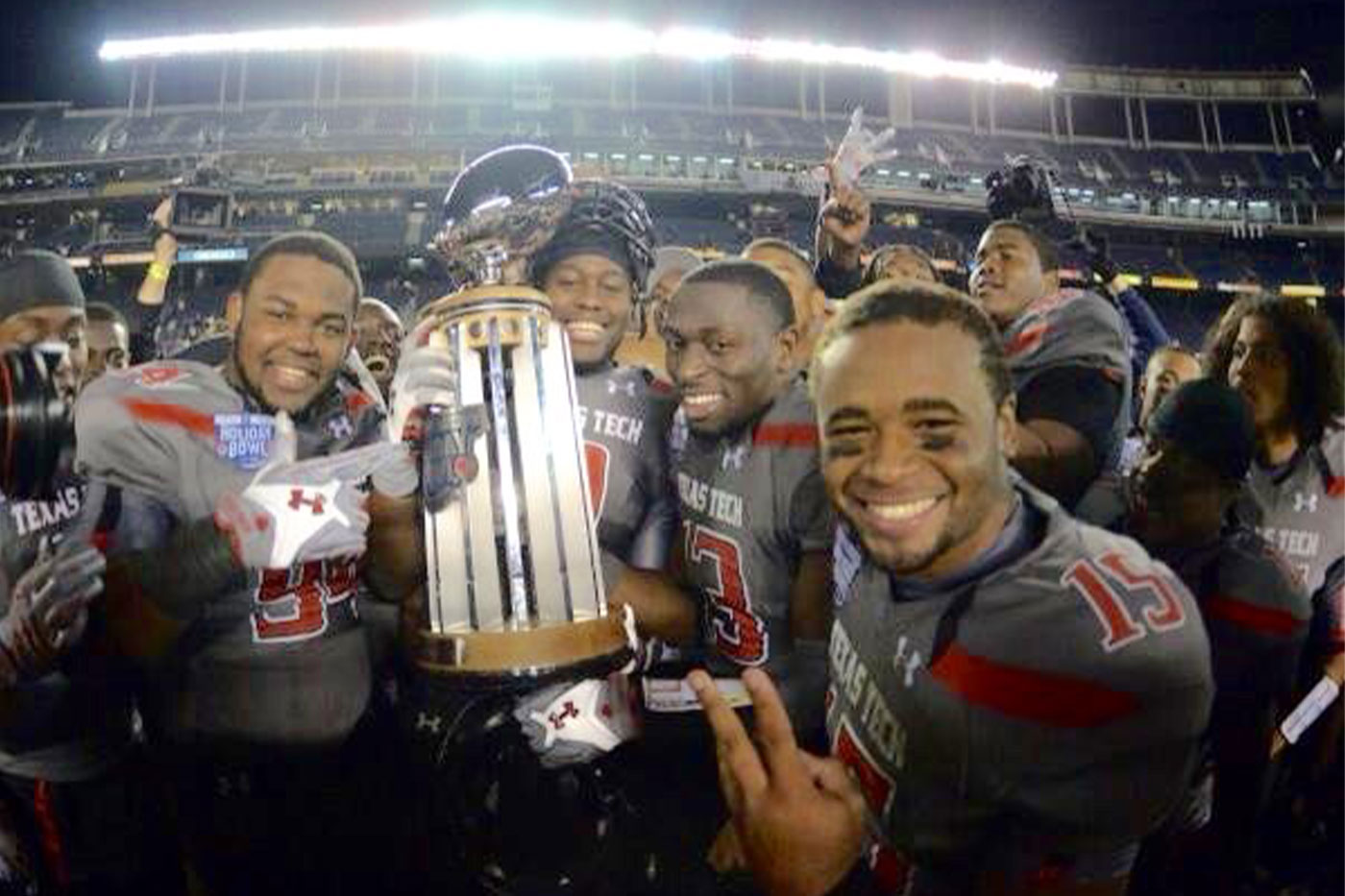

Donte’ was having a good run with the Red Raiders. He had two bowl championships under

his belt going into his third year; he and the team were on an upward trajectory.

Kliff Kingsbury became the head coach in 2013, and there was a tangible excitement

around the program.

In an Oct. 18 home game against the Kansas Jayhawks, Donte’ found out he’d be starting

for the first time.

“I was a solid player,” he said. “I was at a place in my career where the NFL was

still a possibility, but I had to put up some really great games my last two seasons.”

That was doable. Donte’ had met with Kingsbury and they created a plan for Donte’

to get where he wanted to go.

That crisp October day was perfect for football. The Jones was packed with spirited

fans, the weather was chilly but not cold, and there was a surprising lack of wind

for West Texas.

Texas Tech was leading 10-0 in the second quarter when Donte’ dove for a fumble. As

he dove, so did Texas Tech safety J.J. Gaines, Donte’s roommate and best friend. Donte’

reached the ball first, but his elbow got pinned to the turf. When Gaines hit him,

he collided with Donte’s shoulder.

“The hit basically exploded my whole shoulder,” Donte’ said. “Because my elbow was

pinned, my shoulder caved and then gave into the pressure, shattering the joint.”

Everyone other than Donte’ immediately realized how bad it was. He was taken back

for an X-ray during halftime, and he still remembers the technician with her kind

demeanor and somber expression.

She saw the X-ray and looked at Donte’.

“Sweetheart, I’m so sorry,” she said.

“I didn’t know what that meant,” Donte’ said, revisiting the anxiety of that day.

By the third quarter, Donte’ returned to the sideline in a sling, not wanting to miss

the second half of the game. As he walked in that direction, Texas Tech trainer Jeremy

Busch met him near the end zone to deliver the news.

“You’re not going to play football again,” Busch said.

The Hardest Choice

Texas Tech sent Donte’s X-rays to the Dallas Cowboys trainer for a second opinion.

The trainer said they’d never seen a shoulder injury that severe.

As his friends celebrated Halloween, Donte’ underwent surgery.

The operation was complicated and started the process of putting the shattered pieces

of Donte’s shoulder back together. Still, the defensive lineman had not given up on

playing.

“I was going to play,” he said. “I was in a sling from October through the following

January, but I was at winter camp and attended spring training.”

He couldn’t participate in contact drills, but he conditioned with the team while

his bone regrew.

“Donte’ scratched and clawed for a role in the defense,” said former teammate Brandon

Bagley. “I didn’t see the injury occur, but I witnessed his rehab process and how

he fought for a chance to return.

“Seeing him in the training facility at 6 a.m. inspired me to have a positive attitude.”

Donte’ was slowly improving and was ready to talk to his coaches about playing in

the fall, when he dislocated his shoulder.

“I simply reached up into a cabinet,” he recalled, “it wasn’t even in training.”

Donte’ saw his surgeon and the young player expressed how he wanted to keep playing.

The doctor patiently listened as Donte’ explained the efforts he’d made over the previous

six months, all the training he’d done.

The surgeon looked at Donte’ and laid out two choices.

“If you keep playing, you’re going to have a permanently dead arm,” the doctor said.

“You can risk that, or you can take medical retirement and preserve your body.”

It was the hardest choice Donte’s ever had to make.

He decided to take a medical retirement.

He set up a meeting with Kingsbury, a conversation Donte’ remembers as difficult for

them both. Donte’ had a great relationship with his coach, one that was rooted in

respect from the start, he says.

He’ll never forget what Kingsbury said when he announced his retirement.

“He said if I could take the same intensity I’d shown in football and apply that to

life, I would be successful in whatever I did,” Donte’ recalled.

But Donte’ wasn’t ready to hear that at the time. He was disappointed and felt lost.

He couldn’t imagine a reality without football, so he stayed close, taking a communications

internship with the athletics department. This gave Donte’ access to the press box

for each game.

“That was the season (former Texas Tech quarterback) Patrick Mahomes’ career took

off,” Donte’ recalled.

Donte’ and Mahomes had both been on the team in 2014, but Davis Webb was the starting

quarterback, Mahomes only in his freshman year.

“Pat and (former receiver) Jakeem (Grant) just went insane in 2015,” Donte’ said.

“That was some of the best offensive football Texas Tech has ever had, and I got to

watch it all.”

A born competitor, Donte’ wanted to play though, not watch.

Without football, Donte’ knew he needed to figure out his future. He had to create

a new plan while still grieving the loss of the old one.

He was in a sports media course at the time taught by Doug Hensley, an adjunct instructor in the CoMC and part of the Office of Communications & Marketing.

“Doug challenged me to determine what I wanted to do,” Donte’ said. “I didn’t know

which way to go with my career, but he was always real with me. He was a big part

of me moving forward, and he was a friend to me.”

Hensley laid out options for Donte’, which resulted in the athletics internship he

ended up choosing.

“I know Donte’ thought he was going to make an impact in football as a professional

athlete, but like a lot of people, just because his plan was redirected, it didn’t

mean his impact had to be,” Hensley said.

A New Purpose

After graduation, Donte’ moved back to Wisconsin. He knew he wanted to work in communications

but still wavered on what that looked like. Did he want to stay in sports? He worried

that could be rubbing salt in a wound.

Not one to sit around the house, he applied for as many jobs as he could find.

His first job was in communications for a company that manufactured phone stands.

It wasn’t a good fit.

“That’s when I decided to go a different route,” Donte’ said.

He became a talent development specialist for ResCare Workforce Services. The job

paired him with individuals who needed to maintain their food stamp eligibility by

pursuing gainful employment or higher education.

The focus was helping improve others’ quality of life.

Donte’ had about 100 clients at any given time, meeting with 10 people each day.

“I was still struggling with the loss of my athletic career,” he said. “Focusing on

helping others was therapeutic. Helping someone else solve their problems helped take

my mind off my own.”

Donte’ experienced a lot of success in this role. He also realized there was an overlap

in the challenges he faced and the challenges of those transitioning to parole – a

demographic represented in his case work.

When people serve time, every minute of the day is planned out for them – when they’ll

wake up, eat, socialize and sleep. In many ways, the life of a student-athlete is

the same way.

“I was in a similar state,” he admitted. “I’ve connected with several former athletes

who have gone through similar transitions. No one prepares you for life after sports.

We know it has to come to an end eventually, and we try to be ready, but most of the

time we’re just not.”

The sudden surge of freedom can be paralyzing.

Helping individuals re-enter society was a chance for Donte’ to preach to himself.

He was energized helping others find their purpose and somewhere in the midst of it,

he found his own.

“That’s when I knew I wanted to go into public service,” he said.

He also met people who didn’t know him as a football player, but purely as Donte’.

One of those people was his wife, Tori.

Donte’ and wife Tori

Donte’ and wife Tori

Donte’ remembers being enamored when they first met but also unsure if he could be

with someone so confident while facing his own demons. Sometime later, they reconnected

and Donte’ let his walls down.

“Tori loved me for who I was; accolades and reputation didn’t matter to her,” he said.

“That’s when I realized she was my person; she loved me even when I didn’t love myself.”

Forever a Defender

The former defensive lineman had been hardwired to protect the end zone. He was now

ready to protect the vulnerable.

Donte’ sought out public service jobs that aligned with his skillset, especially opportunities

that would utilize his communications experience. In 2019, he landed his first role

with the Wisconsin Department of Justice as a digital investigator.

The role focused on fraud. Donte’s job was to work for the DOJ Division of Criminal

Investigation in partnership with the Social Security Administration’s Office of the

Inspector General to identify offenders who were fraudulently receiving Social Security

disability funds.

“I’d review the cases and find what I could to verify allegations submitted by claimants

online,” Donte’ said.

He combed through social media to verify information that helped close cases. Donte’s

early interest in social media was paying off. What he’d observed in 2011 when starting

college had only become more prevalent in the years since. Every industry was changing

due to social media.

After three years, Donte’ was promoted to senior communications specialist in the

Office of the Attorney General.

The demographic he now protects is one of the most vulnerable.

“Unfortunately, there’s a lot of child-focused crimes right now,” Donte’ said.

With the endless possibilities of the internet, so comes abuse of that technology.

With artificial intelligence (AI), it’s only getting worse.

A focus of the division of criminal investigation (one of nine departments Donte’

serves) is its Internet Crimes Against Children Task force. One key issue targeted

is sextortion, an emerging form of child exploitation.

According to a news release Donte’ wrote, sextortion is a form of child sexual exploitation

where children are threatened or blackmailed, most often with the possibility of sharing

with the public a nude or sexual image of them by a person who demands additional

sexual content, sexual activity or money from the child.

Even if a child knows not to accept friend requests from someone they don’t know,

many platforms now allow for direct messaging between parties who are not connected.

There has recently been a dramatic increase in financial sextortion, according to

the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC). The NCMEC recently

launched an interactive experience online that allows parents and caregivers to see the reality of financial sextortion

through a film.

When the ransom is paid, it’s often not the end. Predators may repeatedly reach out

for more money. Even if the situation does deescalate, the effects on a child’s mental

health can be catastrophic.

“We’ve witnessed a troubling increase in suicides nationwide due to this issue,” Donte’

stated.

This offense is becoming even easier with the rise of AI, as predators can mimic the

voices of a loved one.

For the task force in Wisconsin, through education and awareness, they’ve secured

more than 220 tips related to sextortion since the beginning of 2023.

Government Affairs Director Chris McKinny has worked with Donte’ on similar projects

for the past two years.

“This is a challenging line of work,” McKinny said. “We deal with subject matter that

can be pretty dark, so it’s important our office feels like a family environment.

Donte’ is a big part of that. He has the type of personality people are drawn to,

and he’s just a pleasure to be around.”

Donte’ and his team will keep pushing back against the darkness.

A True Red Raider

Donte’ is no longer tackling an opponent on the field; he is tackling a bigger threat.

“I believe football prepared Donte’ for the great work he is doing today,” Bagley

said. “Donte’ wasn’t in control of what happened to him, but even in that, he embodied

what it took to be a Red Raider.”

Other members of the Texas Tech community marvel at what Donte’ has accomplished,

but they’re not surprised.

“I am just so proud of what he has done and where he is,” Hensley said. “Donte’ struck

me as someone determined to make a difference in the world, and he is committed to

doing that.”

While a large percentage of that drive came from football, Donte’ traces his fierce

protection of the underdog back to his family.

“I watched my dad work as a public defender my whole life,” he said. “He also showed

me the value of developing my own beliefs and becoming a leader, rather than a follower.”

Donte’ didn’t see many Black men working in public service other than his dad. He

said that was a tremendous influence in his life.

“He taught me how important it is to be that representation,” Donte’ said.

Now Donte’ is paying that forward.

In addition to his work with the DOJ, he is a mentor with the African American Youth

Initiative, a program that uplifts and empowers youth of color toward higher levels

of academic performance. Donte’s mentorship is focused on breaking the educational,

cultural and social divide through advocacy.

This is one of three programs for which Donte’ volunteers.

Donte’ Phillips

Donte’ Phillips

“I had a support system,” he said, thinking of the family, coaches and teachers who

helped pull him out of his darkest times.

“You never know what others are going through or if they have that support.”

When Donte’ thinks back on his life, he can see how his adversities set him up to

be who he needs to be.

“I strive to be a source of optimism for everyone I meet,” he said. “By approaching

life with this mindset, it’s enabled me to be myself and serve however I’m needed.”