Open this photo in gallery:

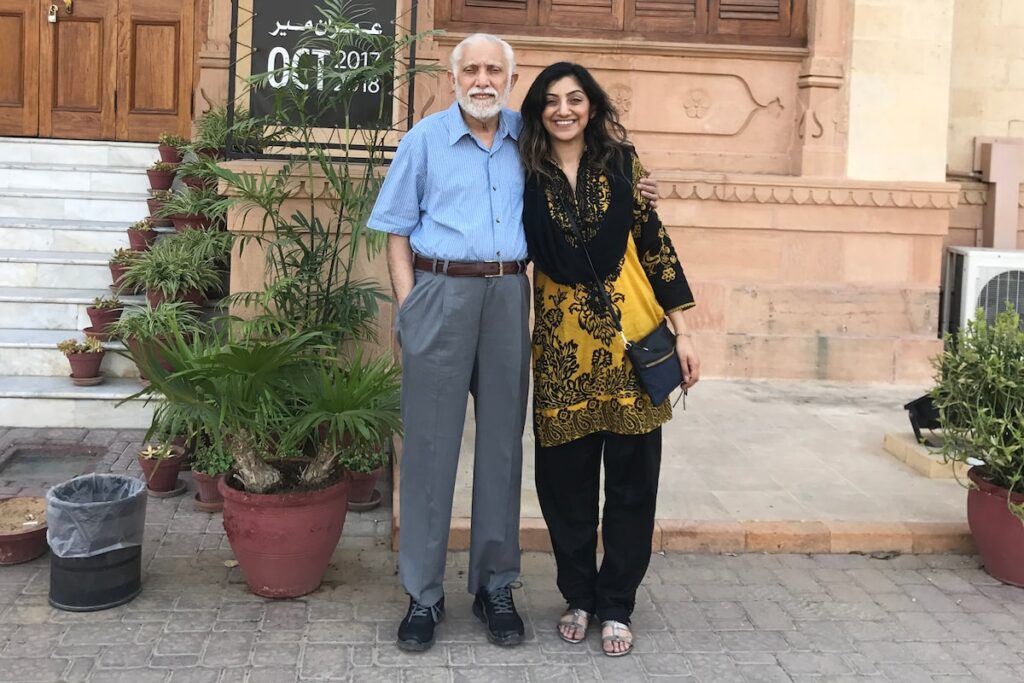

Sadiya Ansari with her father outside Mohatta Palace in Karachi, Pakistan, March 2022. Courtesy of Sadiya Ansari

Sadiya Ansari is a London-based journalist and author of the upcoming book, In Exile: Rupture, Reunion, and My Grandmother's Secret Life.

Six years ago, when I arrived at Karachi's Jinnah International Airport, my father, Rafi, was standing just outside the airport's main entrance, waving excitedly at me. He had managed to push his way through a dense crowd of eager relatives and was dressed for a 4 a.m. start to work, wearing beige slacks and a crisp button-down shirt under a navy blazer.

It was then that I realized we had never traveled together just the two of us.

Two weeks were fast approaching, and I was already worried that I wouldn't have time to accomplish what I set out to do on this trip: to get to Harunabad, a small town in Punjab, 1,000 kilometers from where I'd landed. The purpose of this visit was even more ambitious than this daunting journey: I wanted to unearth traces left by my paternal grandmother, Tahira (whom I called Dadi), during the 15 years she lived there after abandoning her children in 1963 to live with a man.

My dad wasn't on board with my plans; he was just there to spend time with his family, with the added benefit of escaping the Canadian winter.

Daddy was a difficult topic for him, and for his entire family. She lived with my parents, sister, and me in a small house in Markham, Ontario, for the last 10 years of her life. I was five when she moved in, and for the first few years, we shared the same bedroom. Daddy was never a particularly pretty child, but it was still a shock to learn, at age 10, that she had cut off ties with her seven children when she remarried after my grandfather's death. The aunts and uncles who had called and visited her regularly had lost contact with her mother for almost 20 years. They eventually reconciled, but no one wanted to ask her about this period of her life.

As a journalist, I began to question the simple narrative that painted her as a selfish woman and a terrible mother, and as I entered my 30s, I became even more curious about her situation: Why did Daddy leave? Why didn't she come back when her second marriage ended? How did she survive? And how did her children survive?

I had a hunch that there was more to the story beneath the veil of shame that shrouded Daddy's life — and, as it turned out, it was enough to fill a book. But when I started, I had little to fall back on. My father rarely shared stories from his childhood with me, or opened up about the impact of losing his father at age 11 and then, in a very different way, losing his mother as a teenager. He hid the most painful parts of his childhood for decades, never bringing them up with my mother, even when she lived with us.

In most families, ancestral myths are passed down from parent to child. In my family, this worked in reverse, and I had to poke, prompt, and convince them to fill in the historical record. My father became my research partner, and after four years and two research trips, I made the progress I had hoped for, in part because of his courage in unravelling a tightly entangled belief that the past must remain untouched. And watching him learn about his mother gave me the unexpected gift of getting to know him in ways I never expected.

On our first night in Karachi, my father and I made our way through the city's torturous traffic to my father's sister's house. My aunt Lubna was leaving the next day to visit her son in Saudi Arabia for a few months, and most of the furniture in her home had been covered in plastic and placed on concrete blocks in preparation for flood season. Seeing the elaborate preparations, I wished there was a way I could prepare my family to protect them from the repercussions of anything I might find out and make public about Dadi.

As I began interviewing families for the book, I often encountered requests to focus on the positive aspects of their history. What was the use, they asked, of digging up what Dadi had tried so hard to bury? And my father and aunt had shown my mother generosity, even at the risk of breaking her heart anew. Lubna showed me framed tapestries that Dadi had woven and began to tell me some familiar stories.

But then she told me how Dadi had surprised Lubna by showing up outside her school not long after she'd first left, and then, more than a decade later, she revealed, he turned up at Lubna's parents-in-law's house, an appearance made all the more awkward by the fact that her parents-in-law had heard that Dadi had died.

My father was listening, and it was clear that this was the first time he'd heard that story, but he took it with curiosity and more grace than I could have. Even though I was in my 70s, I think I was overcome with jealousy. Why was she visiting her sister and not me?

Like most of my conversations about Daddy's disappearance, we talked about the event that would define the rest of her life: being forced into marriage at 14 to a man 20 years her senior who already had seven children. My grandfather had died long before I was born, and I'd only ever heard him speak of with great reverence, but on the Uber ride back to where we were staying, my father reflected on the circumstances of his parents' marriage.

Like many girls and women of her time, the conventional wisdom was that his mother had no power in her first marriage, but I watched as he questioned his father's decisions, and it was the first time I'd heard anyone in the family think about it aloud.

“Why did he marry her?”

My first visit to Karachi in 2018 was just the beginning, and although my father was supportive of my efforts, there was a limit to how far I could go. Later, when we visited the site of his former home and I asked him to tell me more about those days, he fell silent. “I don't have many happy memories,” he said. He refused to go to Harunabad, saying it would be impossible to visit the place where my mother disappeared.

However, in 2022 I found myself at Karachi airport again, this time with a flight to Harunabad.

On the first trip, even though I knew I was the one driving the agenda, part of me expected my father to take the lead. It was his country more than mine, and he was a parent, after all. This time, I realized that I had to take the lead on this project. I was the one to organize the itinerary into remote parts of Pakistan and know how to look up names and addresses.

What's more, the pandemic has also accelerated my father's aging, as we both feel a sense of urgency to finish projects. I moved to Berlin during the pandemic, and living in a foreign country has accelerated that even more. My father was just as enthusiastic as he was four years ago as he waved to me outside the airport. This time, standing next to my mother who had joined us, I could see that he was shrinking, the excess fabric of his short-sleeved button-down shirt flapping in the breeze.

Open this photo in gallery:

Sadiya Ansari's father looks up at the low-rise apartment block where her childhood home was located in Karachi's Nazimabad district in March 2018. Credit: Sadiya Ansari

From Karachi, we took a 1.5-hour flight in a 48-seater propeller plane to the eastern edge of Pakistan, in the province of Punjab. I knew that once we got to Bahawalpur, my father would be eager to get to the first interview, but he was exhausted from the journey and needed to rest. When we got back, I wanted to take my parents to the city's famous palace, but he was reluctant.

So I worried about how my father would handle the packed three-hour drive to Harunabad, and how he would react when he met our host, Wajahat, the son of Dadi's closest friend in Harunabad, the man Dadi had raised after he left his father and brothers. But he was ecstatic to meet Wajahat.

Wajahat's wife served us chai while her husband told us all about Dadi's time in the small town. He wanted to hear from his father what happened after Dadi left. The woman who had brought them together had died more than two decades ago, but the exchange between them was candid and emotional.

After we finished recording the interview, Wajahat looked directly at my father and asked, “Why didn't you go and see your mother?” I interjected, afraid that my father would be angry, but my father explained with an air of embarrassment that his older siblings, who had supported his brothers since Daddy left, were adamantly opposed to them having a relationship with their mother. Wajahat didn't press further.

We visited the house where Dadi lived and the school where she taught, and met those who knew and loved her. It was a real pilgrimage.

At the end of our day in Haroonabad, my father confided in me his regret: he wished he had visited my mother when she lived there. I reassured him, saying that at least now he could travel, something no one in our family had ever done. He looked at me and said, “I never could have done it without you.”

As any child of immigrants will tell you, the gratitude for what your parents did for you runs deeper than you can ever hope to articulate, let alone mine. My attempts to get to know Daddy better may have been unsuccessful. Hearing him thank you felt like the smallest thing I could do to repay him, helping to bridge a gap that seemed impossible.

In addition to what I learned about Daddy, I was grateful for what I learned through this project about my father: his curiosity overpowering his pride, his ability to genuinely change long-held beliefs, and, most of all, his optimism, still hoping that my mother would not choose to abandon him.

But what I'm most grateful for is that we both realized that by researching our family history, it's never too late to get to know our parents as people.

Despite the role reversal on our projects, I still need my dad to hold my hand from time to time. Earlier this year, I submitted the final manuscript of my memoir, then took my first proper vacation in years. But as I anxiously woke at dawn, staring at my MacBook in the lobby of a boutique hotel in Tenerife, Spain, the panic I'd managed to contain while writing the book bubbled to the surface. What if the rest of my family had an adverse reaction to what I'd written?

I called my dad in Karachi and confessed my fears, and that morning, as a parent again, he reassured me with his characteristically airy yet wise tone: “If you don't like it, write the book yourself.”