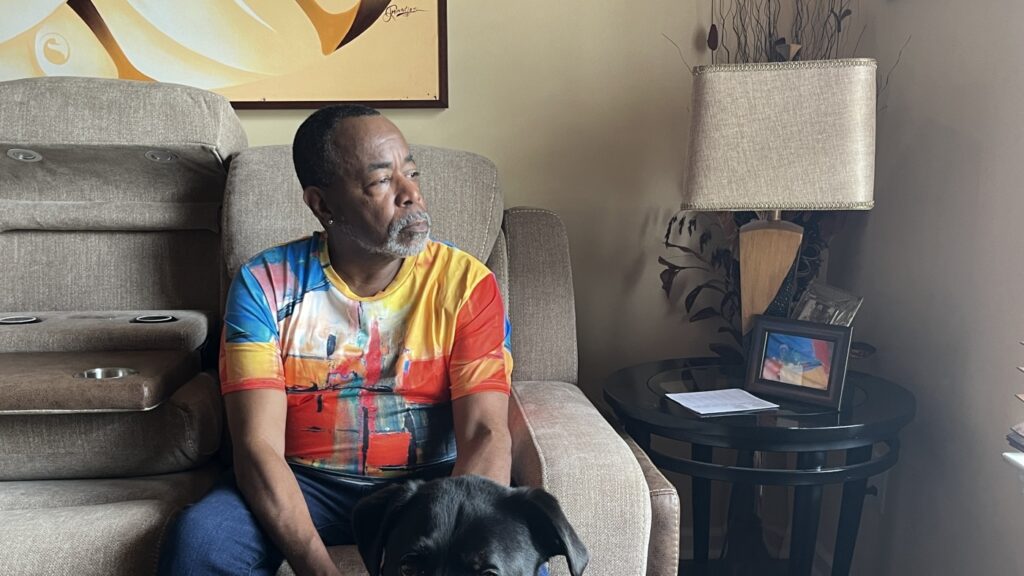

Malcolm Reed spends time with his dog Sampson at his home in Decatur, Georgia. Reed, who recently celebrated his 66th birthday and the anniversary of his HIV diagnosis, is part of a growing group of people over 50 who are infected with the virus. Sam Whitehead/KFF Health News Hide caption

Toggle Caption Sam Whitehead/KFF Health News

DECATUR, Georgia — Malcolm Reed recently took to Facebook to mark the one-year anniversary of his HIV diagnosis. “Diagnosed with HIV 28 years ago and today, thriving,” he wrote in an April post, which garnered dozens of responses.

Reed, an advocate for people with HIV, said he's blessed to have lived to 66. But as he's gotten older, he's also come with a host of health challenges. He's beaten kidney cancer and now takes medication for HIV, high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes. “There's a lot to manage,” he said.

But Reed isn't complaining. When he was diagnosed, HIV could have meant death. “I'm just happy to be here,” he says. “I wasn't supposed to be here, but here I am.”

Like Reid, more than half of people living with HIV in the United States are over 50 years old. Researchers predict that by 2030, 70% of people living with HIV will be in this age group. Aging with HIV means you're at higher risk for other health problems, like diabetes, depression and heart disease, and you're more likely to develop these illnesses at a younger age.

Over 500,000 people

But the U.S. health care system is not prepared to meet the needs of more than 500,000 people over the age of 50 — both those already infected with HIV and those who have recently become infected — according to HIV advocacy groups, doctors, government officials, people with HIV and researchers.

They worry that a lack of funding, an increasingly dysfunctional Congress, flaws in the social security net, untrained health care providers and workforce shortages could worsen the health of aging people with HIV and undermine the larger fight against the virus.

“I think we're at a tipping point,” said Dr. Melanie Thompson, an Atlanta-based internist who specializes in HIV treatment and prevention. “It would be very easy to lose all the great progress we've made.”

The development of antiretroviral therapy, drugs that reduce the amount of virus in the body, is allowing people to survive the virus longer.

However, older people living with HIV are at increased risk of health problems related to inflammation caused by the virus and long-term use of strong medications. Older people often need to coordinate their care with multiple specialists and are prescribed multiple medications, increasing their risk of drug side effects.

“Double stigma”

Some face what researchers call “double stigma” — ageism and anti-HIV prejudice — and also higher rates of anxiety, depression and substance use disorders.

Many people have lost friends and family to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Loneliness puts older adults at higher risk for cognitive decline and other conditions, and it can lead to patients dropping out of treatment. “This is not a problem that can be easily solved,” says Dr. Heidi Klein, an HIV researcher and clinician at the University of Washington.

“If I had the ability to write a prescription for a friend who was supportive, engaged, and willing to go for walks with me twice a week, the care I provide would be so much better,” she says.

The complexity of care poses a major burden for the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, a federal initiative for low-income people with HIV that serves more than half of those infected with the virus, and almost half of its recipients are over 50.

“Many of the people aging with HIV were in the vanguard of HIV treatment,” says Laura Cheever, who oversees the Ryan White Program for the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Researchers have a lot to learn about how to best meet the needs of these populations, she says.

“We're all learning as we go, but it's definitely difficult,” she says.

The Ryan White program's base budget has remained roughly flat since 2013, despite an increase of 50,000 patients, Cheever said. The Biden administration's latest budget request calls for an increase of less than 0.5% of the program's budget.

Cheever said local and state public health officials are making most of the decisions about how to spend Ryan White's money, and limited resources can make balancing priorities difficult.

“How do you decide where to spend the next dollar when so many people are lacking care?” Cheever said.

The latest infusion of funding for Ryan White, totaling $466 million since 2019, comes as part of the federal government's efforts to end the HIV epidemic by 2030. But the program has come under fire from Republican lawmakers, who tried to defund it last year despite it being launched by the Trump administration.

That's a sign of waning bipartisan support for HIV services, putting people “at extreme risk,” said Thompson, the Atlanta physician.

She worries that the increasing politicization of HIV will prevent Congress from appropriating funds for a pilot program to repay student loans for health care workers, aimed at attracting infectious disease specialists to areas with health care shortages.

Many older people with HIV are covered by Medicare, the public health insurance program for people over 65. Studies have shown that Ryan White's privately insured patients have better health than those on Medicare, which researchers link to better access to non-HIV preventive care.

About 40% of people with HIV rely on Medicaid, the state and federal health insurance program for low-income people, and the decision by 10 states not to expand Medicaid could leave older people with HIV with few places to get treatment outside of Ryan White Clinics, Thompson said.

“The risks are great,” she said. “If we don't pay more attention to our care system, we are in a very dangerous situation.”

Reed, the Atlanta HIV advocate, said about one in six new diagnoses is in people over 50, but public health policies haven't kept up with that reality: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, recommends HIV testing only for people between the ages of 13 and 64.

“We have an outdated system. For some reason, we believe that once you reach a certain number, you stop having sex,” Reid says. Because of this blind spot, older people are often only diagnosed after the virus has destroyed the body's infection-fighting cells.

Funding for improvements

Recognizing these challenges, HRSA recently launched a $13 million, three-year program to look at ways to improve the health outcomes of older adults with HIV.

Ten Ryan White Clinics across the U.S. are participating in the effort, testing ways to better track the risk of harmful drug interactions for people taking multiple prescription medications. The program is also testing ways to better screen for conditions like dementia and frailty, as well as streamlining the referral process for people who may need specialty care.

Jules Levin, 74, executive director of the National AIDS Treatment Assistance Project, who has been living with HIV since the 1980s, said he hopes the new strategy will come soon.

His group was one of the signatories to the “Glasgow Declaration,” an international coalition of older people living with HIV that called on policymakers to improve access to affordable health care, allow patients to spend more time with their doctors and combat age discrimination.

“It's a tragedy and a shame that older people with HIV have to suffer like this because they don't get the proper care they deserve,” Levin said. “Without solutions, it will quickly become a catastrophe.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom producing in-depth journalism on health issues and is one of the core operating programs of KFF, an independent source of health policy research, polling and journalism.