Frances S. Barry is the author of Back Roads and Better Angels: A Journey Into the Heart of American Democracy.

In his recent speech in Normandy, President Biden highlighted the choice between democracy and autocracy facing the world, underscoring a fact that has become clear since he launched his reelection campaign in January: He is running not just as a Democrat, but as a Democrat himself.

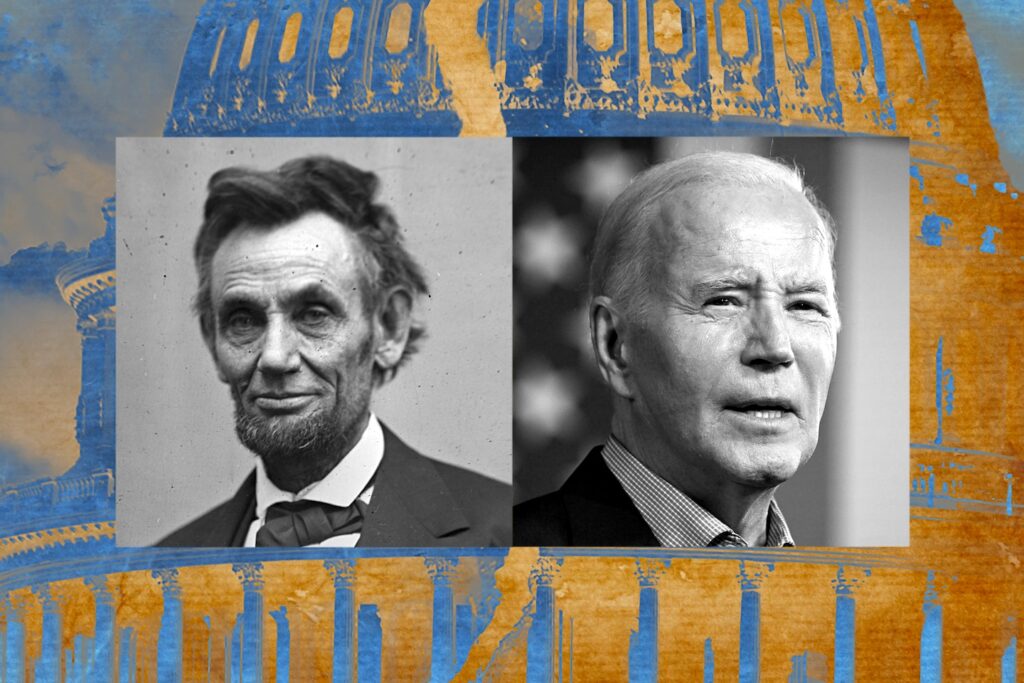

Can he turn the election into a referendum on democracy — and win? The answer may depend on whether he learns from the political blunders made by a man he often admires: Abraham Lincoln.

Biden's defense of democracy at Normandy was so banal that any Republican president after World War II could have easily said it. But some Republicans attacked it as partisan. In fact, every time Biden defends democracy, Republicans try to portray him as “Division in Chief.” Their campaign strategy is to push their biggest weaknesses onto their opponents, just like Lincoln was accused of leading the country to war in 1858 after uttering one of the most famous and enduring political rhetoric of all time.

“A house divided against itself cannot stand,” Lincoln said as he launched his campaign for the U.S. Senate, quoting the New Testament. He was warning that if pro-slavery advocates succeeded in spreading slavery in the territories, as permitted by the Kansas-Nebraska Act, they would try to make slavery legal everywhere.

This quote has been quoted by most modern presidents and has often been used to rally the nation together during election season, but as Lincoln scholar Allen Guelzo points out, it's often forgotten that it may have contributed to Lincoln's defeat in the Senate.

While Lincoln sought to inspire unity against the expansion of slavery, Democrats instead attacked him, accusing him of stoking tensions and leading the nation toward conflict, which is exactly what the Democrats themselves did through their support for the Kansas-Nebraska Act and growing discussion of secession.

While faith in the Bible is bipartisan, Lincoln's “all-or-nothing” rhetoric gave his opponents an opportunity to paint him as a divisive extremist. Republicans are now doing much the same with Biden, who has tried to rally voters around another sacred text, the Constitution, and argues that MAGA Republicans threaten the country and our democracy.

Given Republican support for efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election, Biden is justified in making this charge, much like Lincoln used the “house divided” metaphor, but that doesn't mean he should.

Attacking Trump supporters allows Republicans to paint Biden's appeal for unity as a fraud, something that didn't work for Hillary Clinton in 2016. Worse, it would affirm the way Donald Trump wants voters to view the election the way some in the South saw the 1860 election as Armageddon: If we don't win, the country is doomed.

If Biden makes a similar argument that democracy will die if he doesn't win, he will be playing on Trump's side, where fear and intimidation can help score points, giving Trump a crucial advantage.

So what can Biden learn from Lincoln?

Lincoln, who was forced to go on the defensive over his “house divided” speech in the first debate with Stephen Douglas, laid out four strategies that Biden could benefit from.

First, he used his wit to make Douglas feel at ease and endear him by mocking his criticism of a Bible passage. Biden, who is adept at flattering Irish-Americans, should have more fun slamming Trump. An old man who can make a room erupt in laughter wins hearts.

Second, Lincoln distanced himself from the party's radical wing, assuring his audience that he was neither an abolitionist nor a believer in black equality, and reaffirming his support for the right of slaveowners to reclaim “fugitives.”The Biden campaign should look for opportunities to emphasize its distance from the party's far-left wing, focusing on issues that Trump has fear-mongered, such as crime, wokeism, and border security.

Third, Lincoln went out of his way to express personal understanding and solidarity with his opponents when he said Southerners “wondered what we would do if we were in their place.” Biden should feel free to say something similar about Trump supporters. That would send a more welcoming message to undecided voters, strengthen his calls for unity, and take away the advantage that Clinton's “a bunch of deplorables” remark gave Republicans.

Fourth, and most importantly, Lincoln reframed the debate. Without giving up any of the principles that mattered to him most—upholding the Founding Fathers' vision of suppressing slavery in order to ultimately abolish it—Lincoln emphasized that regional differences were part of the “bonds of the Union.” In other words, as long as Americans had faith in the Founding Fathers, a house divided could stand.

Biden, too, can remain steadfast on the principles that are most important to him: the rule of law and the peaceful transfer of power. But he can also emphasize that tolerating differences, even on the most contentious issues, is what unites a nation. A deeply divided nation can be united as long as we respect the rule of law and what underpins it: the results of elections.

While these tactics were not enough to lead Lincoln to victory in 1858, they ultimately helped propel him to the White House and remained hallmarks of his leadership.

Lincoln retracted his “house divided” remark and welcomed secessionists as “friends” in his inaugural address, referring to their “bonds of affection” and calling on “our better angels” to “sing up the chorus of the Union.” Though he could not prevent the war, his refusal to rightly denounce his opponents earned him the support of Northern Democrats for his reelection and saved the country.

If Biden runs a divided campaign, he will likely recall Lincoln's fate in 1858. But if he runs a more benevolent campaign, he could rekindle the Confederate chorus and begin to heal the nation's wounds, just as Lincoln hoped in his second term.