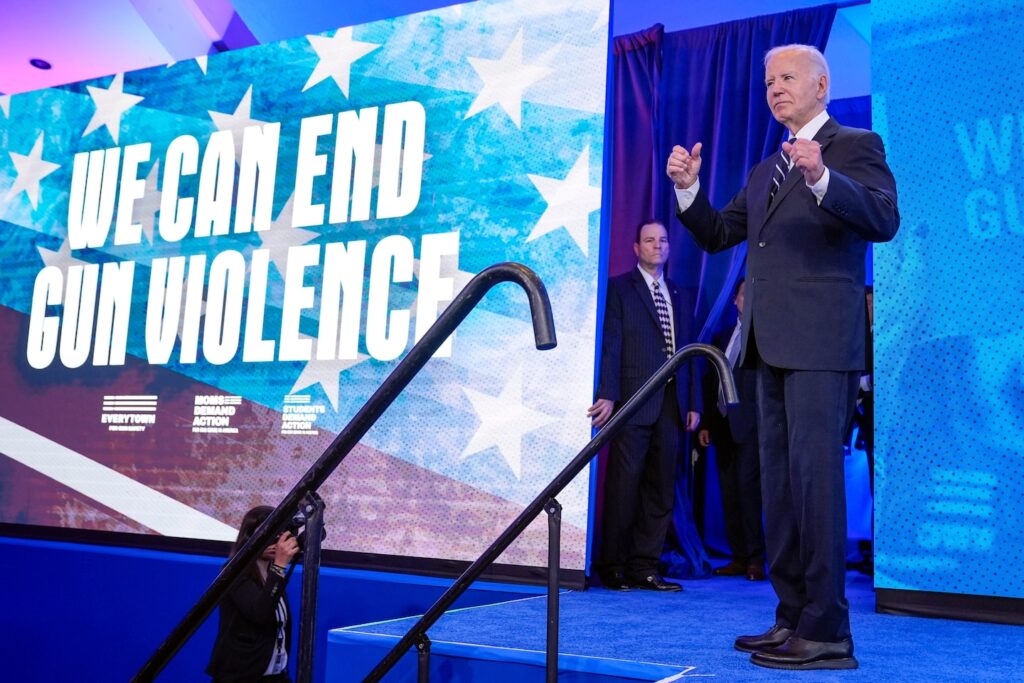

Like many official acts emanating from the executive branch of government, Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy's declaration on Tuesday that gun violence constitutes a public health crisis achieved both a policy outcome and a political outcome. The policy outcome is that the move brings both attention and resources to efforts to combat gun violence. The political outcome is that, as The Washington Post noted, voters have seen at least some action on a problem that has come to be viewed as insolvable.

But gun violence in America isn't just about mass shootings that garner so much attention and fear — it's also about the many people who use guns to take their own lives, with rates varying widely across countries.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention uses death certificates to compile data on causes of death in the U.S., including the total number of firearm-related deaths each year as well as the number of deaths by type of firearm. The most recent CDC data is from 2022, and the last three years of CDC data show the sharp increase in firearm deaths that Mursi noted in his declaration.

Even in 2022, most of these deaths are from people who took their own lives. According to CDC data, in 2020 and 2021, the percentage of gun deaths that were suicides was lower than in any year since 1999. The percentage that were homicides was higher. But in 2022, the percentage of gun deaths that were suicides rose.

The rate of gun deaths relative to state population varies by state. For example, Washington DC and Montana have high gun deaths relative to their population, while New Jersey and California have relatively low gun deaths.

DC also has far more deaths from assaults, i.e. murders. In states like Utah, the majority of deaths are suicides. In other states, including much of the South, the murder numbers are far higher.

But the recent rise in gun deaths pales in comparison to the sharp increase in overdose deaths, which has been driven by a rise in fentanyl deaths, though overdose deaths were on the rise even before fentanyl emerged several years ago.

Opioid overdose deaths (including the synthetic opioid fentanyl) were declared a public health emergency in 2017. That year, the CDC recorded three overdose deaths for every two gun deaths in the United States, up from a one-to-one ratio six years earlier. In 2022, there were two opioid deaths for every gun death.

Preliminary data for 2023 released by the CDC shows that gun deaths in the United States did not increase that year, but instead fell by 5% — a steeper decline than the 3% decline in overdose deaths recorded during the same period.

Guns kill tens of thousands of people every year, and of course there remains a political incentive to bring these deaths to public attention.