Unlock Editor's Digest for free

FT editor Roula Khalaf has chosen her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In its latest World Economic Outlook, the IMF calls what is currently happening a “mega-city lockdown.” I prefer “The Great Shutdown.” This phrase captures the reality that even if policymakers did not impose lockdowns, the global economy would have collapsed and may remain collapsed even after lockdowns end. But whatever you call it, this is clear. This is the biggest crisis the world has faced since World War II and the biggest economic disaster since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The world enters this moment with divisions between great powers and appalling incompetence at the highest levels of government. We will pass through here, but what will we enter?

In January, the IMF had no idea what was about to happen. One reason for this is that Chinese officials were not communicating with each other, let alone with the rest of the world. We are currently in the midst of a pandemic that has huge implications. However, much remains unknown. One key uncertainty is how short-sighted leaders will respond to this global threat.

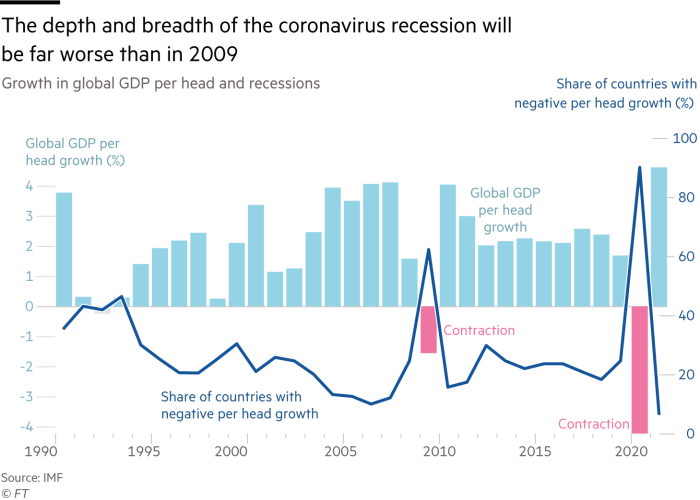

For what it's worth, the IMF currently suggests that global per capita output will fall by 4.2% this year, down from 1.6% in 2009, recorded at the height of the global financial crisis. % is significantly higher. This year, 90% of the country is expected to experience negative growth in real per capita gross domestic product (GDP), compared to 62% in 2009, although China's strong economic growth has cushioned the blow.

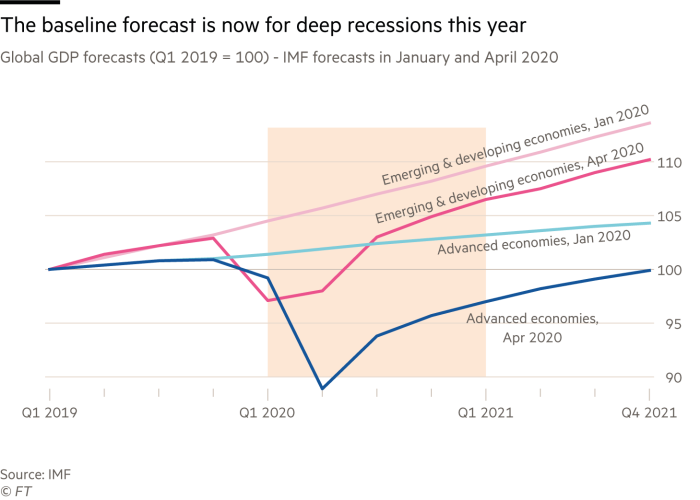

In January, the IMF predicted healthy growth this year. It is now expected to decline by 12% in developed countries from the last quarter of 2019 to the second quarter of 2020, and by 5% in emerging and developing countries. However, optimistically, the second quarter is predicted to be the bottom. We expect a recovery thereafter, but production in developed countries is expected to remain below 2019 Q4 levels until 2022.

This “baseline” assumes the economy will reopen in the second half of 2020. In that case, the IMF predicts that in 2020 the world economy will shrink by 3%, then in 2021 it will expand by 5.8%. In developed countries, economic growth is expected to be 6.1%. It is expected to contract by 1 percent this year and expand by 4.5 percent in 2021. All this may prove to be too optimistic.

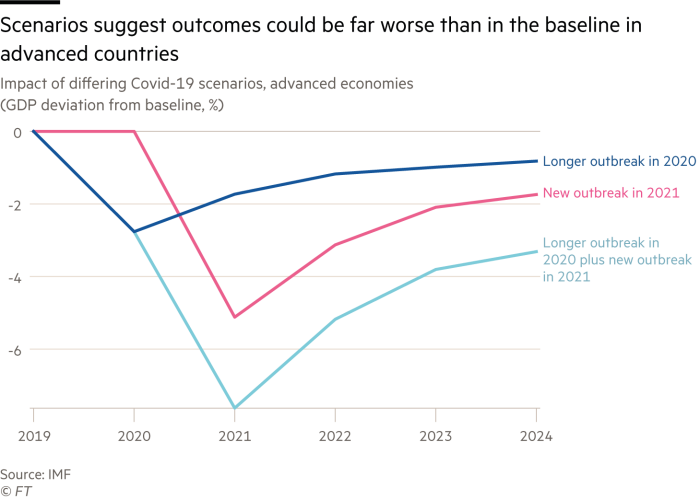

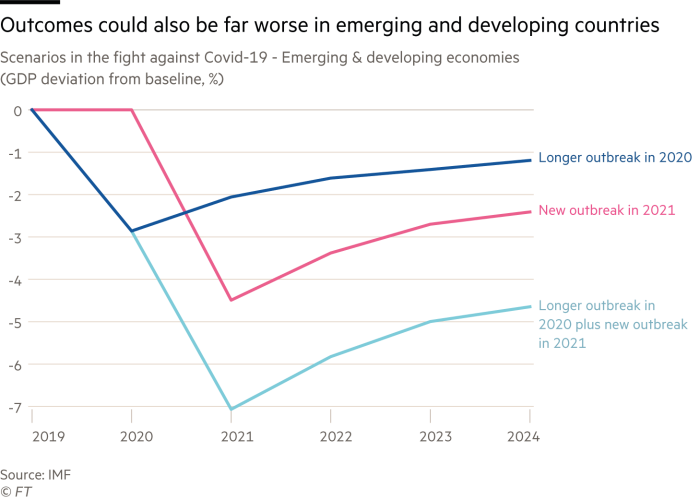

The IMF offers three sobering alternative scenarios. In the first, the lockdown lasts 50 percent longer than the baseline. In the second, there will be a second wave of the virus in 2021. The third combines these elements. Due to the prolonged lockdown this year, global production in 2020 will be 3% lower than the baseline. A second wave of infections would cause global output to fall 5% below the baseline in 2021. If both misfortunes combine, global output will be almost 8% below the baseline in 2021. Under the latter possibility, government spending in developed countries would decline. This would result in a 10 percentage point rise in GDP relative to the already unfavorable baseline in 2021, and a 20 percentage point rise in government debt over the medium term. We have no idea which one will prove to be the most correct. It could be worse. Viruses may mutate. Immunity for people who have been infected may not last. And a vaccine may never be developed. Microbes have turned all our arrogance upside down.

What must we do to deal with this disaster? One answer is not to abandon the lockdown before mortality is brought under control. It will be impossible to restart the economy as infections rage, deaths rise, and health systems are overwhelmed. Even if they were allowed to go back to shopping or working, many people would not do so. But it is essential that we prepare for that day by significantly increasing our capacity to test, trace, isolate and treat people. No expense should be spared in this regard or in investing in the creation, production and use of new vaccines.

In particular, the introduction to a report by the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington on the important role of the 20 major economies and regions (G20) states: That means more people die. ” This is also true in health policy and ensuring an effective global economic response. Both the pandemic and mass shutdowns are global events. As former IMF Chief Economist Maurice Obstfeld highlights in his report, support for the health response is essential. But so is economic aid to poor countries through debt relief, subsidies, and cheap loans. We need a huge new issuance of IMF special drawing rights that transfer unnecessary allocations to poorer countries.

The negative-sum economic nationalism that drove Donald Trump throughout his term as US president, and has even manifested itself within the European Union, is a serious danger. We need free trade, especially (but not exclusively) in medical equipment and supplies. If the global economy collapses, as happened in response to the Great Depression, the recovery will be undermined, if not destroyed.

We don't know what the pandemic will bring or how the economy will react. We know what we must do to get through this terrible havoc with the least amount of damage.

We must get the disease under control. We will need to make huge investments in the systems to manage it once the current lockdown ends. We must spend whatever it takes to protect both our people and our economic potential from the consequences. We must help the billions of people living in countries that cannot help themselves. Above all, we must remember that no country is an island in a pandemic. I don't know the future. But we know how to shape it. Will we? That's the question. I am very concerned about our answer.

martin.wolf@ft.com

Follow Martin Wolf on myFT. twitter

Video: Martin Wolff: Coronavirus could be the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression

Source link