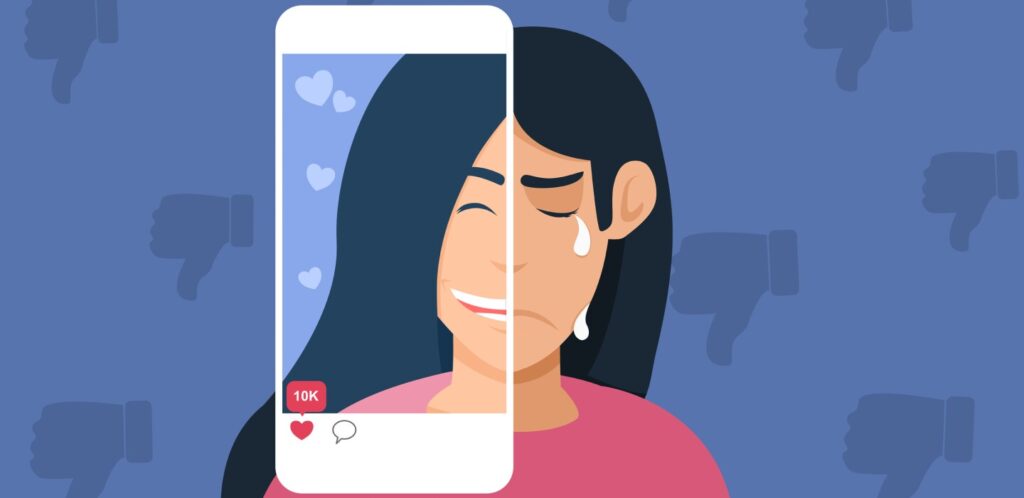

(TNS) — America's youth are facing a mental health crisis, and adults are constantly debating how much to blame phones and social media. Jonathan Haidt's book, An Anxious Generation, has sparked a new debate. The book argues that the rise in mental health problems in children and adolescents is a result of social media replacing important experiences during the formative years of brain development.

This book has been criticized by scholars, and rightly so. Haidt's argument is based primarily on research showing that youth mental health has declined since 2010, around the same time as mass smartphone adoption. But of course, correlation is not causation. Our existing research suggests that the effects of phones and social media on adolescent mental health are likely more subtle.

This complex situation is unlikely to garner as much attention as Haidt's claims because it does not have much of an impact on parents' concerns. After all, when I see kids hooked on their phones and hear that their brains are being “rewired,” I think of alien plans for world domination straight out of sci-fi movies.

And that's part of the problem with Screen Time's “rewire your brain” narrative. This reflects a larger metaphor in public discourse of using neuroscience as a fear tactic without yielding much real insight.

First, let's consider what we have learned from previous research. Meta-analyses of the association between mental health and social media yield inconclusive or relatively minor results. The largest U.S. study of children's brain development to date found no significant relationship between developing brain function and digital media use. This month, the American Psychological Association. The health advisory states that the current state of research shows that “social media use is neither inherently beneficial nor harmful to young people,” and that its effects depend on “their existing strengths and weaknesses and the environment in which they grew up.” reported that it depends on

So why do Haidt and colleagues argue that smartphones risk rewiring the brain? It stems from a misunderstanding of research that I frequently encounter as a neuroscientist who studies emotional development, behavioral addictions, and people's reactions to media.

Imaging studies in neuroscience typically compare features of parts of the brain between two groups: one that does not perform a certain behavior (or one that does it less frequently) and one that performs that behavior more frequently. When we find a relationship, what we mean is that either that behavior has some effect on the functioning of this brain function, or that something in this function influences whether or not we participate in that behavior. Either you are giving it.

In other words, the association between increased brain activity and social media use suggests that social media activates identified pathways or that people who already have increased activity in those pathways tend to be drawn to social media. It may mean that there is, or both.

Fear-mongering occurs when the mere association of a brain pathway with an activity, such as social media use, is seen as itself a sign of something harmful. Functional and structural studies of the brain do not provide enough information to objectively identify increased or decreased neural activity, or “good” or “bad” thickness of brain regions. There is no default healthy status quo for measuring everyone's brain, and nearly every activity involves many parts of the brain.

The Anxious Generation ignores these subtleties, for example, when discussing the brain system known as the default mode network. When we engage in spirituality, meditation, and related endeavors, the activity of this system decreases. Hite uses this fact to argue that social media is “not healthy for anyone.” Because research suggests that social media, by contrast, increases activity within the same network.

But rather than externally focused thoughts, such as playing chess or driving an unknown route, the default mode network is focused on internally focused thoughts, such as contemplating the past or making moral judgments. It's just a set of brain areas that tend to be involved in focused thinking. Increased activity does not automatically mean some kind of ill health.

This type of brain-related fear tactic is not new. A popular version, also deployed in smartphones, includes pathways in the brain associated with drug addiction, such as areas that respond to dopamine and opioids. This metaphor states that any activity associated with such pathways, such as Oreos, cheese, God, credit card purchases, tanning, and looking at beautiful faces, are as addictive as drugs. These involve neural pathways associated with motivated behavior, but that doesn't mean they damage our brains or should be equated with drugs.

Adolescence is a time when the brain is particularly plastic or changeable. But change isn't always a bad thing. We should use plasticity to help teach children healthy ways to use smartphones and self-manage the emotions surrounding them.

Can we expect future research on the adolescent brain to immediately alleviate parental concerns about this issue? Of course not. And the point is, you shouldn't. Brain imaging data is an interesting way to investigate interactions between psychology, neuroscience, and social factors. It is not a tool to declare behavior pathological. Feel free to question whether social media is good for kids, but don't abuse neuroscience to do so.

© 2024 Los Angeles Times. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.